A Cola Q&A with Tim Burgess

City Council member Tim Burgess—along with Bruce Harrell, one of two council members hoping to unseat Mayor Mike McGinn—is, fairly or unfairly, regarded as the candidate for "conservative" Seattleites: People who believe in law and order, who support harsher restrictions on "broken windows" crimes like panhandling and graffiti, and who support a "fix it first" approach to infrastructure over ambitious (some would say fanciful) proposals like citywide light rail.

Burgess won his council seat after a tough battle with then-incumbent David Della in 2007. His one and a half terms in office have been defined publicly by several key legislative fights in which he seemed to be on the conservative side of various issues.

He resisted the paid sick leave ordinance until he orchestrated a compromise that the business community was happier with. (Clearly, though, they didn't like it that much—as they're down in Olympia this session working to overturn it.) He also pushed legislation to crack down on aggressive panhandling that ran into trouble with civil rights activists; Mayor McGinn vetoed the legislation.

Burgess was also the chair of the public safety committee in the runup to the Department of Justice's damning report on police conduct, which has led to DOJ oversight of the SPD.

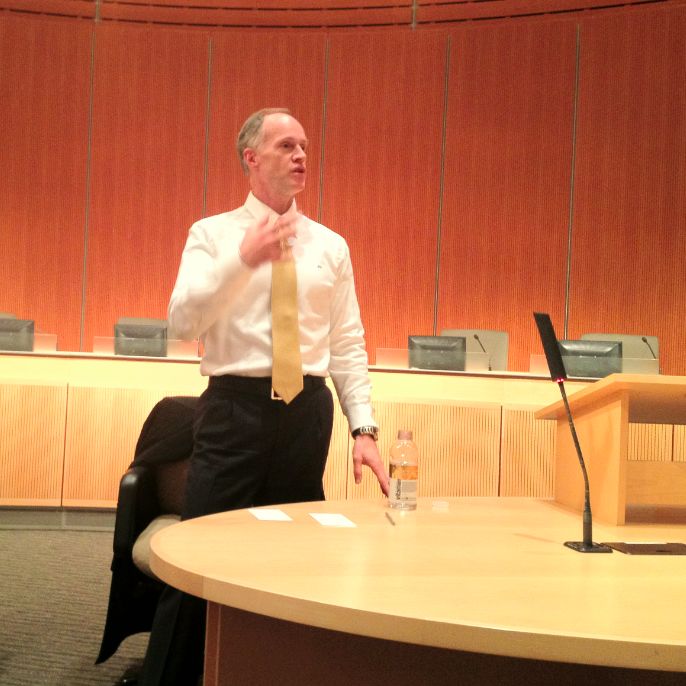

We sat down with Burgess at PubliCola's office last week.

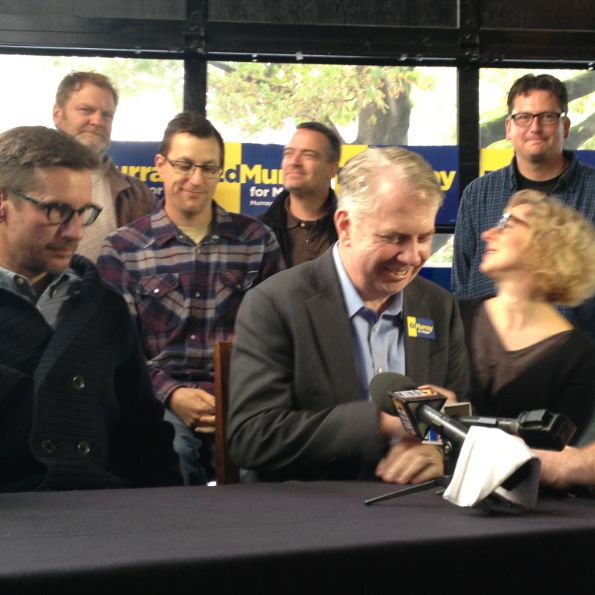

Here are our interviews with incumbent Mayor Mike McGinn and the other challengers—Bruce Harrell, Ed Murray, and Peter Steinbrueck.

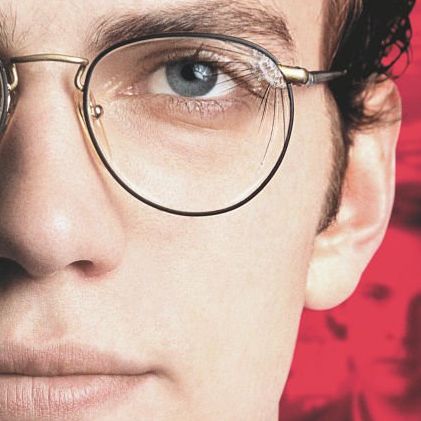

Photo by Carryn Vande Griend.

PubliCola: We've had some trouble understanding your professional trajectory. Can you explain your arc—from doing poverty relief work overseas, to being a journalist, to being a cop, to being on the ethics commission, to being a consultant, to running for city council?

Tim Burgess: My family was very poor. We lived in North Capitol Hill, on the east side of Volunteer Park, and my mom worked as a cook at Meany Middle School. It was Meany Junior High in those days. That was when Seattle Public Schools had real kitchens.

It was a working-class, Catholic and Jewish mixed community. I would leave Stevens Elementary and walk to Meany after school—its about eight blocks, nine blocks—because all the kids of the cooks would come there after school and we'd eat leftovers.When I was 12, my parents had to move because they lost their house to foreclosure. My dad sold office supplies downtown. He literally sold office supplies door to door downtown. So when they lost their house to foreclosure, we moved further north, by the University bridge. I went to Lincoln High School.

Right out of Lincoln, I got a job at KJR Radio. That's where Pat O'Day, the legendary disc jockey of Seattle, worked. And I worked in the news division there for about four years. I covered City Hall and Olympia.

PubliCola: So you were a teenager in the '60s—that was a crazy time. What was your interaction with that era? Were you a hippie or a square?

Burgess: I was a nerdy square, and in fact, at Lincoln High School—I would not want to admit this—I was on the AV squad. We had projectors, 16 millimeter film, and I knew how to wind up cords on my arm and stuff.

PubliCola: Were you an anti-war kid? Or did all that stuff pass you by?

Burgess: I was not involved in a lot of that stuff. I remember covering [now-King County Council member, then-Black Panther] Larry Gossett. [Former mayor] Norm Rice and I were both radio journalists and we ran around town together.

I covered a lot of police issues. There were a lot of bombings and shootings in the city, a lot of civil disorder, and then I covered the corruption trials. I'm the only person who's worked as a city employee, other than elected officials, who's running.

And then Wes Uhlman was elected mayor. He was a young state legislator who ran on a reform plank: "I'm going to clean up City Hall." I was very enamored with that and wanted to be part of that. So I quit KJR and joined the police department.

My time in the police department was very eye-opening for me, in terms of the effects of violence, injustice, poverty. I had a pretty sheltered life up to that point, and being a police officer on the street is not a sheltered life. I went through a period of struggle—what am I doing, where am I going, what's life all about?

There was a spiritual issue there, too, and I really felt motivated and interested in global poverty issues. So I quit the police department and went to work for a humanitarian organization, and spent the next seven years doing anti-poverty work around the world, mostly in East Africa, some in South Asia, for World Vision, which is the largest Christian humanitarian organization in the world. I worked for World Concern, which is a baby brother to them. So I did that for about seven years. And that's where I learned nonprofit management marketing and all that stuff.

And so in 1985, I started my communications consulting firm to serve nonprofit organizations and help them communicate their messages. And I ran that for 20 years until 2005. I grew it from just me, and then after about three years, I brought on a business partner, a friend of mine, who became my partner. And then we sold it.

And then I was going to retire and I thought that would be really boring. So I talked to my wife and daughters and said, "I think I'm going to run for city council," which kind of made sense, at least in my mind.

In fact, I'm the only person who's worked as a city employee, other than elected officials, who's running [for mayor]. I was a police officer for seven and a half, almost eight, years, and during the time I had my business I served on the Ethics and Elections Commission for 12 years, including five years as chair, and then I wanted to do more, to give back to my community.

PubliCola: You call yourself a progressive, but as a consultant, you represented Concerned Women for America, a group that opposes gay and women's rights. How do you justify that? Why did you choose to represent them?

Burgess: We represented a pretty wide array of nonprofits—some political, some social services, some religious, some focused on kids. We took CWA as a client, and consciously did that, in the early 2000s. And after a while, we realized that this maybe is not the type of client we want. We had complaints from employees, especially our gay employees. So we developed an opt-out program so that they didn't have to work on that client's assignments if they didn't want to, and I eventually persuaded my business partner that we don't want to represent this organization, and that took a while—a couple of years—and we resigned the contract.

[Erica broke the story about Burgess and CWA back in 2007.]

PubliCola: You're obviously a deeply religious guy. How does your faith inform your politics? [The panhandling ordinance] was not in any way something that was anti-humanitarian or anything like that. That was an attempt to address an issue which we still have today.

Burgess: It influences me on justice issues, it influences me on issues of equality, and it's kind of one of the core intellectual motivations of my life as to where I spend my time and what I do and how I view challenges and issues as an elected official. It doesn't dictate to me how I make my public policy decisions, but it certainly has an influence in terms of social equality, justice, these types of things.

PubliCola: In terms of the panhandling controversy, the pushback seemed to be coming from a humanitarian angle. Was your proposal compassionate?

Burgess: I've never linked those two. Look, everybody in our city deserves to be safe. And that was, as you'll remember, a measure that passed the city council and had the support of all of the social service agencies downtown who work with the homeless. They supported that ordinance. Bill Hobson, the director of DESC, testified in front of the council [in favor of the ordinance.]. Some of the housing providers, Plymouth Housing and others, supported that legislation.

That was not in any way something that was anti-humanitarian or anything like that. That was an attempt to address an issue which we still have today.

PubliCola: So you don't regret it?

Photo by Carryn Vande Griend.

Burgess: I don't regret it. I think we still have challenges of safety on our streets, and we need to be creative and try all kinds of things.

PubliCola: So if you were elected mayor, what would you propose to deal with the current problems with street disorder?

Burgess: I would fundamentally reform how we do policing in Seattle and how we approach criminal justice to shift from what has traditionally been the American response to crime, which is after the fact, responding after a crime has occurred— you call 911, they come—to a very proactive prevention orientation.

We see that in many progressive cities in our country that are doing that very, very well, so that police are viewed as partners. As opposed to coming in to neighborhoods to do things to people, they are partners with the community to create positive outcomes for safety and security.

PubliCola: Can you be more specific? Everyone talks about positive outcomes. What does that mean on the ground? What does that actually look like?

Burgess: It looks like what we've seen at 23rd and Union, for example, and the Drug Market Initiative [a program in which police gave drug dealers an ultimatum: Stop dealing and go free, or go to jail].

It's really hard work, it's really labor intensive. It puts the police in partnership with communities, understanding their needs and their expectations. It involves an assessment of what the crime problem is and establishing a baseline and measuring against that over time. It's very outcome-oriented. It's measuring impacts. It truly is a prevention orientation so that people, especially young people, don't get started in the direction [of crime].

It involves the use of much more data-driven orientation. It's a cultural change for the police and a different mindset, and it's really hard work.

PubliCola: On the subject of police reform: McGinn resisted the DOJ plan and the choice of the police monitor. One way you could look at that is that he's getting the backs of the rank and file, because they agreed with him. If you're talking to a rank and file officer, how do you explain to them that this is a good thing?

Burgess: I have lots of rank and file police officers who've talked to me, and my firm conviction is that 98 percent, 99 percent of the women and men who serve our city as police officers want to do the right thing. They want to serve with distinction. They want their work to be successful. And they are desperate for clear leadership and direction. It's kind of like they're leaning in, waiting, and it's not there. So I don't agree that the rank and file is resistant to change at all. We've had three and a half years now of failed leadership, of divisive leadership—a mayor who chooses conflict over collaboration. We can't afford to have that continue.

PubliCola: But the police union is suing to stop the monitor's proposal. Doesn't that represent the views of the rank and file?

Burgess: I'm not going to characterize the union. My experience is what I said. Our officers want to do the right thing; they want to serve with distinction. The union's lawsuit is on a very narrow technical issue related to collective bargaining, so that lawsuit is not about reforms. [Filing their case in King County Superior Court on March 11, the police union said they weren't opposed to reforms but felt the agreement violated their collective bargaining rights.—Eds.]

PubliCola: You've rolled out a very back-to-basics transportation plan. Mayor McGinn is presenting a more urbanist proposal focusing on light rail and mass transit. This is a city that has gone for light rail overwhelmingly over and over again. Are you ceding a major issue to him?

Burgess: I've been a huge advocate of light rail, of the streetcar network, and expanding it. But the system has to work as a whole, and I think we have neglected some of those basics, like street and bridge maintenance and repair. And what I was pointing out is, as we do these good things, like light rail and the streetcar, we dare not forget the basics.

Bicyclists don't like potholes, drivers don't, and transit buses don't. You've got to take care of all that at the same time.

PubliCola: But all of the shortfall in maintenance funding happened during, first, a time when construction became exponentially more expensive, and then during the Great Recession. Can you really blame McGinn for that?

Burgess: Again, I just go back to the continuing rise in the backlog. We're going to have to renew Bridging the Gap [the 2006 transportation levy] in 2015, and if the voters don't have the trust and confidence that the leaders of the city can spend that money wisely, that money is at risk. And we need to not only renew that, we need to increase it to a larger amount. So it's critically important that we demonstrate that we know how to do that.

We've had three and a half years now of failed leadership, of divisive leadership—a mayor who chooses conflict over collaboration. We can't afford to have that continue. And that's going to be the central issue of this campaign.

This conflict with Pete Holmes [for example] started the day after December 16, 2011, when the DOJ issued their report. And it was conflict not only with Pete Holmes, but with council president Sally Clark, council member Bruce Harrell, and myself. We engaged in an attempt to negotiate with the mayor to collaborate and figure out how we could resolve the DOJ challenges that we faced, and from day one he chose not to do that. So I don't see the conflict with Peter as some new thing that just happened. It's been that way the whole time.

PubliCola: So if you found yourself in a situation, as mayor, where your lawyer disagreed with the city attorney, what would you do?

Burgess: I would have definitely dealt with him differently. If you look at my time on the council, my style and my approach is to sit down with people and work out problems.

You brought up the panhandling ordinance, and throughout that whole debate, before the passage on the council, I sat down with those in favor and those opposed many, many times, including Tim Harris of Real Change [who opposed the panhandling proposal]. And after that was all done, and Real Change moved to their new offices in Pioneer Square, Tim called me up and asked me to cut the ribbon. That warmed my heart, because we had a disagreement, but we were able to be respectful and remain friends to the point that he wanted me to come and cut the ribbon. I left the police department to go work at anti-poverty programs. That's a little unusual. Cops don't often do that. I did that because of core motivations deep in my soul to work with the poor.

I think [Mayor McGinn] chooses conflict over collaboration. That's not productive. I'm not going to make it personal. I just don't like that level of discourse. I disagree with his approach. I disagree with his management ability. I mean, has he run anything before he was elected mayor of our city? It's not a personality conflict with Mike, it's that I just don't think he's doing an effective job as mayor, and I would do it differently.PubliCola: So what policy decisions of his will you reverse if you're elected?

Burgess: I would be taking a very different approach on the whole police reform issue and a lot of other policies. I didn't like his execution on the new proposed sports arena. We analyzed his proposal and said there's no way we're going to pass this, and eight of us signed a letter to Mr. [Chris] Hansen and said, we're sorry, this is not going to be approved unless you can come back and renegotiate with us.

And we've done that on the mayor's proposed rezone in South Lake Union, which was wholly inadequate on balancing public and private benefits. We had to reject the Block 59 proposal [in South Lake Union], and now we're working on some solutions to better balance that out. So it's about leadership and it's about how the city government is being run and managed. We have to make it better and balance the public and private benefits. That's just an illustration of how I would approach governing the city very, very differently.

Burgess: My answer on that so far is that I'm waiting to see the legislation that council member Rasmussen is developing. I haven't seen it yet.

I think aPodments can be done correctly in the city, but I don't know what this legislation is going to say. It's very complicated legally, and that's why I want to reserve judgment on that specific piece of legislation. But I am very strongly in favor of concentrated density.

PubliCola: What does "concentrated density" mean?

Burgess: We've said in city policy before I came on the council that we're going to concentrate density in urban villages, urban centers, station areas, and along major transit corridors so that, one could argue, we can protect single-family neighborhoods in our city.

PubliCola: You have support from a lot of education reform advocates. Would you be excited to get an endorsement from Stand For Children [the pro-charter school, ed reform group]? Would you be proud to be the education reform candidate?

Burgess: I don't know if they get involved at the local level, but I do have very strong convictions about the need to improve public education. In 1967 [when Burgess was graduating high school], the adults were talking about successful north end schools and failing south end schools, and here we are in 2013 having the exact same conversation. And for me, that's a fundamental justice issue. We need to make changes in how we do public education.

I'm also very close to the teachers union and their leadership. I don't bash teachers or the union. I'm very proud of what they have done with their creative approach schools—which is kind of their version, if you will, of charter schools—where they've made some substantial waivers of provisions of their contract to allow for innovation.

PubliCola: You got a bunch of contributions from former department heads. They're all coming to you, not other candidates. Did you solicit them? Why do you think they're coming to you?

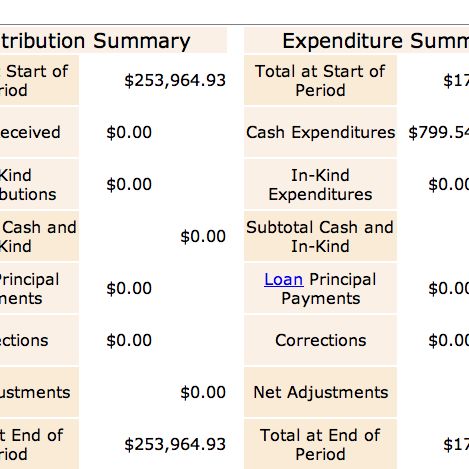

Burgess: I have lots of former and current city employees who come up to me and ask me how they can support me. I have a great relationship with city workers. [Burgess has received nearly $1,900 from city employees, making city employees among his top contributors.] They're a really important group of ten and a half thousand people who serve our city, and I've got great relationships with them, and it's actually very gratifying to me that current and former city employees want to support my campaign. I didn't specifically reach out to them, but I have talked to many of them on policy issues.

PubliCola: We asked you the other day about whether you'd fire Peter Hahn, given your criticisms of the transportation department. You said no. What are your plans for other department heads? Is there anyone else, besides [SPD Chief] John Diaz, you'll ask to resign? [Burgess has said if he's elected mayor, he will get rid of Diaz.]

Burgess: Here's what will happen when I'm elected, and this happens with any new administration: All those department heads will submit their resignations and then we'll have a conversation and a discussion and figure out what's best for the ongoing management of the city government.

PubliCola: Who do you consider the best Seattle mayor in your lifetime?

Burgess: Besides Bertha Knight Landes?

PubliCola: I don't think you were here then. [Landes was mayor in the 1920s.]

Burgess: I wasn't, but I've read a lot about her. She was a character. She got elected on an anti-corruption platform and appointed herself as chief of police, and after she was elected she revealed that she was part of the women's temperance movement, and the voters threw her out after two years.

It's always tough to pick your favorite mayor. I've known the mayors all the way back to Floyd Miller, Gordon Clinton, who just passed away. Charley [Royer] and Norm [Rice] would probably be among them.

PubliCola: Have either of them endorsed you?

Burgess: Charley has.

PubliCola: Why do you think Nickels lost, and what do you learn from that?

Burgess: I think Greg kind of lost touch with the street and the people. I think he made an error when he gave the administration a B-plus on the [2008] snowstorm. I think if he had said something along the lines of, this was really tough and we made some mistakes and we have a lot to learn, people would have been very forgiving. But I think the combination of maybe losing touch a bit and that kind of worked against him.

PubliCola: What was your take from the KING 5 poll [which showed Burgess in second place behind McGinn, with 9 percent]—what's positive and what's challenging?

Burgess: I was very pleased. It showed me in second place, and at the beginning of the campaign, before the public phase of the campaign has really started much. I was very encouraged.

And I'm glad [former King County executive] Ron Sims made the decision he did [not to run: Sims tied with McGinn at 15 percent in a hypothetical matchup].

PubliCola: How do you get the undecideds to go your way? You've got a liberal state senator who can clearly raise money, you've got former city council member Peter Steinbrueck, who has the support of a lot of liberal housing advocates. And then that leaves you with the conservatives. Is that enough to bring you through?

Burgess: I don't necessarily agree with that analysis, but I'm appealing to every voter in Seattle who wants their city government to share their values, get things done, and make sure that city services, the basics, are delivered effectively and efficiently. And that's what I will do. I was raised in a very conservative, fundamentalist home, and I moved away from that. I didn't do that overnight. So yes, my views politically, religiously and in many, many other ways have changed over time.

PubliCola: And those values are…?

Burgess: Gosh, there's lots of them. The values of justice and social equality. Look at my record on the council—on paid sick leave, I was the deciding vote. On the wage theft law, which I introduced and passed after I learned about the oppression of low-wage workers in our city. Helping to shift the police focus to see that prostituted children are victims, not criminal suspects, and launching the prostituted children's rescue fund.

PubliCola: You've said you're a born-again progressive. Can you explain that?

Burgess: I left the police department to go work at anti-poverty programs. That's a little unusual. Cops don't often do that. I did that because of core motivations deep in my soul to work with the poor. And that was back in the late 1970s.

PubliCola: What did you used to believe that you no longer believe?

Burgess: I was raised in a very conservative, fundamentalist home, and I moved away from that. I didn't do that overnight. So yes, my views politically, religiously and in many, many other ways have changed over time.

I'll give you an example. I wasn't a campaigner for it, but I strongly supported the death penalty. As I saw how our country administers the death penalty, I no longer believed we can do it fairly and justly, and that changed my opinion about that. And I also saw through the evidence that the death penalty is not a deterrent to homicide. I was invited by the coalition that opposes the death penalty to testify about the legislation in Olympia that would ban the death penalty.

PubliCola: That's legislation that your opponent, state Sen. Ed Murray, has been pushing.

Burgess: Good for him. He's an excellent legislator.

PubliCola: If you could have one endorsement what would it be?

Burgess: Washington Conservation Voters. That's an organization that takes a very rational, progressive view on environmental concerns. I've had their endorsement in my two previous campaigns for the city council. I'd probably like the Sierra Club too, but I think they've already gone with somebody else. [The Sierra Club has endorsed their former local boar chair, current Mayor Mike McGinn.]