Around the Clock at Pike Place Market

Before the onslaught of tourists, the arcade enjoys a few moments of silence.

Image: Amber Fouts

The Morning Rollout

On Pike Place Market time, 8:45 isn’t exactly early. The fish market guys were here at 5:30 to break down halibut; the flower stalls had their buckets filled with peonies and irises by 7. The main arcade is mostly empty, save the strains of a busker’s morning warmup on her violin. But at the farthest reach of the North Arcade, the swarm of vendors is seven people deep and spreading. Still more have climbed on the worn concrete slab countertops for a better view. There’s a slight fizz of anticipation in the cool morning air as everyone trains their gaze on a whiteboard that’s clearly been tacked up for ages.

Beyond the permanent produce stands known as high stalls are the flat tables for farmers who claim their specific turf via reservation the day before. The rest are for the day-stall vendors, who make anything from cheese boards to bongs to liners for rubber boots. Every morning for half a century they report for roll call, a ritual jockeying for the most desirable stall their seniority will allow, an old-school Wall Street trading floor reimagined with more flowing beards and fleece. But also a genuine sense of community; some of these men and women have spent decades side by side at these tables.

Day-stall program coordinator Maggie Mountain is one of the five market staffers who handle the daily roll call.

Image: Amber Fouts

Posted over the board are the 230 people eligible to sell crafts in Pike Place Market. They’re listed in seniority from Bob Crew of Metamorphosis Leathers, who has been here 40 years, down to the handful of newcomers approved a few weeks ago. Technically guys like Crew have the market’s equivalent of tenure; other senior vendors can dart up and lay claim to their preferred location with blue dry-erase marker—provided they do it before Zack Cook rings the bell at 9am sharp to start the day’s roll call.

Cook, bearded and baby faced beneath his Pike Place Market cap, usually works with the farmers (he even visits their fields to confirm they actually grow their own wares). Today it’s his turn as designated market master, ready to rattle off the names of the vendors assembled before him, in order of seniority, and record their requested location. The faster this goes, the more time everyone has to set up before Cook does his compliance rounds at 11.

Munko? Two sixteen!

Seppa? Bridge sixty-three!

Parriott? Fourteen out, please.

Yocco? Two twenty-four dogleg.

The covered arcade spots go first, then the bridge; given the sunny forecast, outside berths go fast, too. At last, Cook hits the final name on his list. He counts down from five, a last call for anyone who wants to change their spot. His blue marker records the time on the board: 9:18am. Roll call over, the vendors scatter to bring their part of the market to life. Racks of art and textiles start to bloom in the gray spaces almost instantly.

Morning at the market means seafood on ice and flower vendors at work. Thomas Marnin of vendor MarninSaylor at work.

Image: Amber Fouts

Roughly 40,000 people will pass through Pike Place Market today. Most of them will never know about roll call, or the 49-page rulebook that shapes who sells what here, and where. By 11am, the arcade fills up. A remarkably tanned couple in shorts and matching San Francisco sweatshirts break their resolute stride to browse Stone City Farm’s goat-milk soaps; two girls in Boise State softball team gear examine the felt Donut Cats at the MarninSaylor booth. A display of art photographs nearly covers the all-powerful whiteboard, hiding in plain sight until the day is done.

Afternoons and Busker Tunes

At the corner of First and Stewart, just a block from Pike Place Market, a woman in the lavender sweatshirt and leggings turns to me with a sheepish expression as we await the green light. She knows locals must roll their eyes at what she’s about to ask. “Am I close to the first Starbucks?”

The man in a mint green button-down next to us turns as we step into the crosswalk—“Don’t feel bad; I just moved here yesterday.”

Just head down to that brick street right there, I told her, and you can’t miss all the Starbucks groupies taking photos. Except, it’s lunch hour: Crowds clog every sidewalk.

At Corner Produce, a vendor who’s a dead ringer for Zach Galifianakis hews off a chunk of a red Jazz apple and offers it to a young woman, along with his finely honed sales pitch: “It’s the jazziest of apples.” Beyond them, and beyond the wall of Instagrammers, is the institution that’s both ambassador and bellwether for the entire market. Once upon a time the vendors here spoke an assortment of languages; now it’s the visitors. Two guys chattering in German weave past a slow-moving tour group whose leader narrates in Japanese. A new slate of musicians takes its turn at the market’s designated busking sites; lively bluegrass permeates the air.

Jaison Scott wields crabs at Pike Place Fish Market.

Image: Amber Fouts

Simply follow the lodestar of the Public Market Center clock, and you can’t miss the Pike Place Fish Market guys. If a big convention of lawyers is in town, they know it. If a cruise ship just docked at Pier 66, its passengers will soon proliferate around the counter. When they do, Jaison Scott is ready.

He and his comrades in aprons are the Flying Wallendas of fishmongering, walking a daily high-wire of salmon-throwing showmanship and legitimate commerce, conducted quickly, and with knives, in very close quarters. “Love the people,” is the mantra they repeat among themselves, a reminder how seriously they take their role as most visitors’ introduction to Seattle. Scott knows how to say assorted phrases in Italian or Tagalog—“most of them ‘I love you,’ to little old ladies”—to break the ice, and hopefully turn audience members into actual customers. He can also spot the regulars, with their canvas bags and “I need something, then I want to get the hell out” look in their eye.

Scott’s mother worked here for longtime owner Johnny Yokoyama in her youth, then ran the counter at the old Wonder Freeze just down the arcade up until the day Scott was born in 1972. When he was an infant, Yokoyama’s mom, Helen, would babysit Scott, tucked in a banana box while his mom worked nearby. That was kind of a thing here, thanks to the market’s particular combination of multiple generations and a preponderance of empty fruit crates. It would be another decade before the day care opened on the lower level.

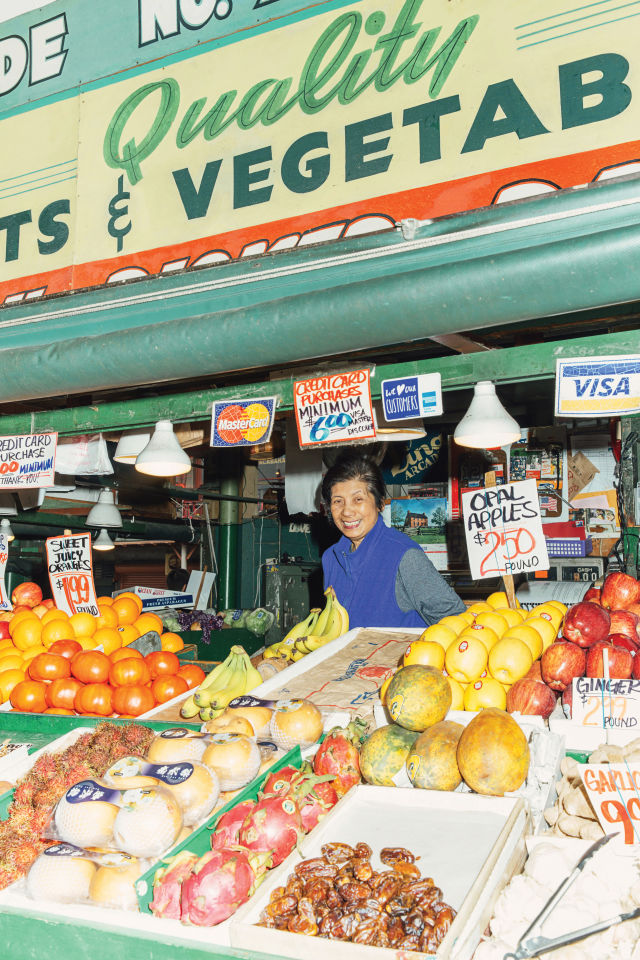

Lina C. Fronda has watched passers-by from high stall no. 7 since 1963.

Image: Amber Fouts

Down the arcade, Lina C. Fronda arranges tomatoes at high stall no. 7, across from Lowell’s. She emigrated from the Philippines in 1963 for an arranged marriage at age 23; he was 59 and brought her to work here the day after her flight touched down in Seattle. “He commanded me like a little kid,” she recalls. “When he address me, he say, ‘Hey kid—do this.’ ” The next year, her infant son Donnie joined her, tucked in a banana box. Now Lina’s 78 and she’s still here, bustling around the stand in patterned yoga pants, washing heads of cabbage. So is Donnie; he handles customers.

Just across the bricks of Pike Place, Mila Apostol’s daughter Joy helps her into one of the high counter seats at Oriental Mart. Apostol also came here from the Philippines and first rented this space in 1971; the market reminded her of the one in her hometown. Originally she sold round, flat baskets while her youngest son dozed in, yes, a banana box. Now her children—and their children—work here. Joy runs the shop; Apostol’s other daughter, Leila, holds court over the six-burner range, beneath an unruly assortment of handwritten house rules—“We do not accept difficult customers, so know your role!”—designed to manage crowds, but also put diners on notice that the hospitality here is as home style as the food.

Leila makes whatever she feels like each day, in summer often the dinuguan stew that’s a hit with Filipino cruise ship workers and flight crews, but pretty much always the sinigang, the brisk tamarind soup she’s adapted with salmon collars. She goes through so many collars that she has to get them from two nearby markets—Pure Fish and Jaison Scott and his crew at Pike Place Fish.

Scott cruises past on breaks, sometimes just to say hi to the women he’s known since he was a kid and peek at the pans of adobo and pancit. “I’m always snacking there, just rice and whatever she has.”

At high noon, when it can take an eternity to traverse a single block, it’s easy to mistake tourists for the dominant narrative of this place. But even amid the crowds, you can see evidence of a generations-old community from the corner of your eye: The day stall vendors who chat between customers; the fishmonger who dashes in on a break to kiss Mila on the cheek.

“We like to support each other here,” says Leila, as she attends to a pan of plump longanisa sausages. “I buy from them; they eat over here. It all kind of works out.” She looks up and spies the trio of twentysomethings directly in front of her display of food. “You have any questions? Oh, not right now?” Even the most oblivious loiterer can’t miss the tinge of reproach in her voice.

Four generations of the Apostol family work at Oriental Mart.

Image: Amber Fouts

Night: When Locals Come Out to Play

By night, the Athenian’s red counter stools sit in tidy, unoccupied rows as the hum of activity shifts to the back bar. The groups that spill out of undersize booths wear the loafers of nearby office life, rather than tourism-friendly sneakers. The crowds drinking beer down on the benches at Old Stove get progressively smaller, and more mellow, as they watch the sun dip behind Elliott Bay. There’s no line at the Pike Place Starbucks for the first time all day, though people mill around inside right up until it closes, at 9pm, presumably seeking decaf.

In the main arcade, rows of stalls are empty and bare; produce and fish stands are locked up and roll-down metal doors barricade the maze of restaurants and shops across the way. But it takes a minute to realize the thing that really reinforces the emptiness of Pike Place Market after hours is the absence of music.

Pints with a view at Old Stove Brewing.

Image: Amber Fouts

Il Bistro, wedged in an alley underneath the heart of the market, is the kind of place that feels shadowy and dim, no matter the hour. “Night belongs to the locals, the people who work here,” says Dan Jansky, the bar manager, as he readies his own riff on a manhattan, made with a cardamom-spiced amaro out of Portland. Seattle’s cocktail scene traces its DNA back to this marble-topped bar, where barman Murray Stenson held court in the 1990s, in the days when a properly made old fashioned was a rare and wondrous thing. Later Stenson moved down the hill to Zig Zag Cafe, where he found national acclaim. These days, Stenson is nearly 70 and tends Il Bistro’s bar on Monday nights, but his legacy lives on here largely in its reputation as a place for bar and restaurant industry folks to drink late at night.

If Il Bistro is semihidden, JarrBarr, a converted storage unit in the market’s postern gulch of Western Avenue, is downright obscured, even from just a few feet away on the sidewalk. You have to know it’s there, but plenty of people do: Good luck getting a table at 5pm, when attorneys and copywriters and the occasional visitor who heard about this place from their bartender the night before converge upon its few tables for sherry cocktails and soft-cooked eggs topped with anchovies or piquillo peppers.

Sherry cocktails at JarrBar as evening falls.

Image: Amber Fouts

By 9pm, it’s quiet, save orchestra-era Quincy Jones that swells on the turntable. Every breath of the night air heightens your awareness that Puget Sound is nearby. Jesse Spring has overseen the bar here from the first day in 2016; he knows this is merely a lull. That the men and women who work at the downtown bars and restaurants will be closed out by 1am. They’ll need to unwind, someplace where the kitchen can still whip up a few snacks and a shot and a beer is just $6 during late-night happy hour.

There are times when Spring has to turn the lights way up at 1:55 to get people to leave, to stagger into the night just a few hours before the fighmongers start their day.

“Then the next night it could be totally quiet,” he says with a shrug, pouring a sparkling Spanish wine into one of JarrBar’s stubby glass tumblers. The market always retains a bit of mystery, even for the people who know it best.