Local Officials Speak Out Against a New Citizenship Question on the Census

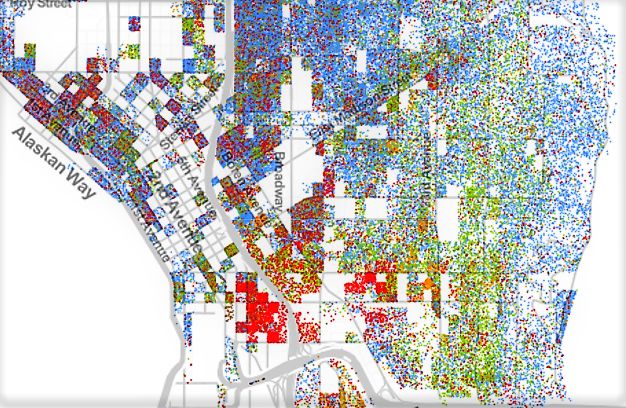

A map of downtown Seattle's racial and ethnic make-up using 2010 U.S. Census block levels (blue=white; green=black; red=Asian; orange=Hispanic.)

Image: Joe Wolf

In the past two years, protecting immigrants has been at the forefront of countless local political discussions.

State legislators passed the Voting Rights Act this legislative session, allowing citizens to request district elections when they show they need better minority representation. Last year a new rule adopted by the state Supreme Court barred attorneys from asking someone in court about immigration status unless it's essential.

But decisions made at the federal level threaten to undo a lot of those efforts to stop immigrants from retreating into privacy, afraid to come out publicly or seek government services. The U.S. Department of Commerce on Tuesday announced that by 2020, the Census will begin asking U.S. residents about their citizenship status again, a question that hasn't been asked since 1950.

“The census has been an American institution for two centuries, and it depends entirely on the people’s willingness to participate openly and honestly," U.S. representative Pramila Jayapal said in a statement Tuesday. "Today’s decision by the Trump administration to include a question about citizenship threatens that open participation."

It's another legal battle against President Donald Trump that Washington attorney general Bob Ferguson said he'll join, following the lead of California and New York. And on the local level, Seattle council member Teresa Mosqueda crafted a letter signed by all nine council members opposing the decision.

Washington state has an estimated 250,000 undocumented immigrants, the majority of whom are in Seattle, according to the Pew Research Center.

"The question, 'Are you a citizen?' sounds like a simple question," Mosqueda said during a council meeting last week. "The reality is that it will sabotage, it will destroy, and it will put at risk our ability to get accurate data."

Opponents say that'll leave non-citizens (whether legal or not) worried about being on the grid with the federal government and deportation avoiding the question, and the Census altogether, leading to inaccurate data that underestimate populations, especially minority ones. Federal and local funds rely on those counts.

So does determining government representation.

Lawmakers use Census's population data to craft congressional and legislative districts. More densely populated, urban areas that have more foreign-born residents also tend to vote blue—and analysts say underestimating minority populations would dilute seats and power for predominantly Democratic areas.