The Museum of Museums Playfully Ponders Its Own Existence

Artist and architect Greg Lundgren's new project opens in February.

Image: Carlton Canary

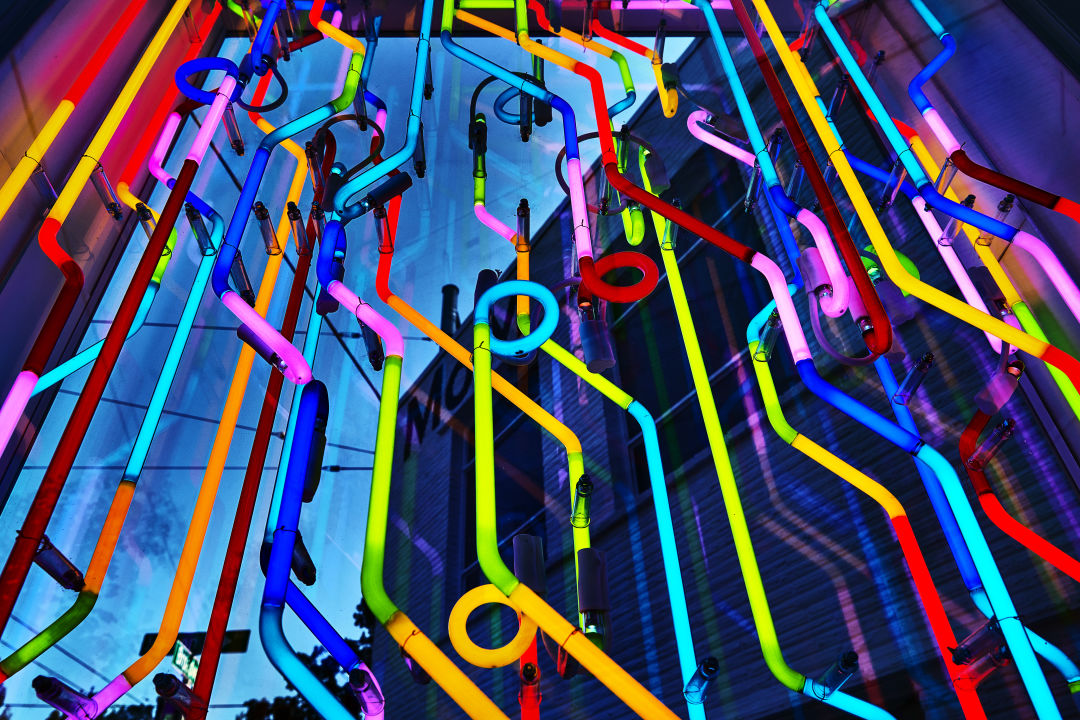

Perhaps the most indicative space in the new Museum of Museums (MoM) is the second-floor bathroom, dubbed the Museum of Museum of Museums. If that tangles your tongue, try Mo MoM. In here the new First Hill for-profit art space, which opens February 7,* will display work about itself. To begin, a series of nude portraits done during construction. Next, perhaps, selfies taken with Dylan Neuwirth’s joyful, twisting neon sculpture, which doubles as a sign near the entrance. Then, maybe, articles like this will end up in there (if you’re reading this on the toilet, art is cathartic!). Either way, the work will, like the galleries around it, be engaged with a question: What is a museum right now and how do we want to interact with it?

MoM is the latest from Greg Lundgren, the compulsively prolific Seattle artist, filmmaker, architectural designer, and entrepreneur. Through his Vital 5 Productions, he co-owns bars (the Hideout, Vito’s) and runs Lundgren Monuments (which imagines headstones as sculptures), as well as a string of exhibitions and venues, like Out of Sight—a popup companion to Seattle Art Fair, which in 2017 showed over 150 local artists.

MoM began, in fact, at Out of Sight. The artist Neon Saltwater (aka Abby Dougherty) contributed an installation—a turquoise hotel room so saturated with 1980s colors that looking at it, you imagine breathy synths, an air-conditioned chill.

Then, last January, during Pioneer Square Art Walk, Dougherty went to Brian Sanchez’s opening at Treason Gallery. Sanchez, like Dougherty, works in colors of psychotropic intensity—his abstract paintings seem to buzz. Lundgren arrived, too, and the three started talking about collaborating on an installation like Dougherty’s at Out of Sight, but more expansive. Lundgren already had a space in mind. The next day, the three stood at Broadway and Marion in front of a long-empty medical building. Three days later they were in serious talks with the owners. By May, Lundgren was sledgehammering walls.

Dylan Neuwirth's All My Friends doubles as signage in front of MoM.

Image: Carlton Canary

When the museum opens, Dougherty and Sanchez’s collaboration, Energy Drink, will command the 1,900-square-foot gallery on the third floor. The show is composed of more than 10 rooms, each a decadently hued environment, heightened with sound and even smell, meant to elicit feeling. In a 3-D rendering of one room, based on a gym, parts of the walls appeared like Sanchez’s paintings—bars of bent color—while Dougherty’s surreal, angular aesthetic was everywhere.

The rest of MoM will overflow with other exhibitions. During a walk-through, Lundgren said he planned to squeeze art into every nook (“You can put a sculpture here. You can put a diorama here. I think to start we’re going to use this as a bay of video monitors”). In the other main gallery, Goodwitch/Badwitch, a group show curated by artist and Instagram icon the Hoodwitch (aka Bri Luna), delves into the way art and the occult interact. The Charles Mudede Theater will feature a film series programmed by The Stranger film critic of the same name. The Talk Show Gift Shop will contain a Johnny Carson–like set, and cashiers may interview customers as they check out.

Then there’s MoM’s most meta piece: Sculptor Jennifer McNeely will create the dollhouse-size Supperfield Museum of Contemporary Art. “Very Charlie Kaufman,” Lundgren says. It’ll run miniature exhibitions she’s solicited from 12 Seattle artists and a website about the SMCA’s fictional curatorial drama—how, for instance, does the tiny museum deal with cultural appropriation?

In part Lundgren was inspired by the newer wave of art venues, like Museum of Ice Cream in San Francisco and Meow Wolf in Santa Fe—places that fold art into an experiential business. At MoM, you’ll pay $10 to enter. Since the space isn’t trying to sell most of the art, the only stipulation is that people want to see what’s inside. This frees it from the gallery model, in which well-off buyers dictate what gets shown and artists like Dougherty can get excluded. She’s offered prints of her 3-D renderings, but “my art career is not really about selling prints,” she says. Rather it’s about “creating rooms that make people feel things.” Rarely, of course, do people buy rooms.

But since MoM is for-profit, Lundgren also isn’t beholden to a typical museum’s board of directors and canonical art. Attendance is the metric, so he wants a space that’s “really accessible and really dynamic.” These days, people see more art than ever, but most of it is through screens. Why not use that fact, figures Lundgren, to draw them to museums? If Energy Drink blows up Instagram and it’s artistically compelling, great. Or, he riffs, if someone can do an intelligent, vibrant show about Nordstrom or Rainier Beer—also great.

Underlying everything about MoM is Lundgren’s mission to turn Seattle from a town with a decent visual art scene to a real hub, a city that not only retains talent but attracts it. In many ways, like its white-painted facades, MoM is a blank slate. If it doesn’t work, it can change quickly to become the sort of art space that Seattle wants and needs. “There’s a lot of room for error,” Lundgren says. “And there’s a lot of room for disappointment, and there’s a lot of room for magic.”

► Museum of Museums Opening, Date TBD, Museum of Museums, museumofmuseums.com

*Updated February 4 to reflect that, due to zoning, the museum opening has been delayed.