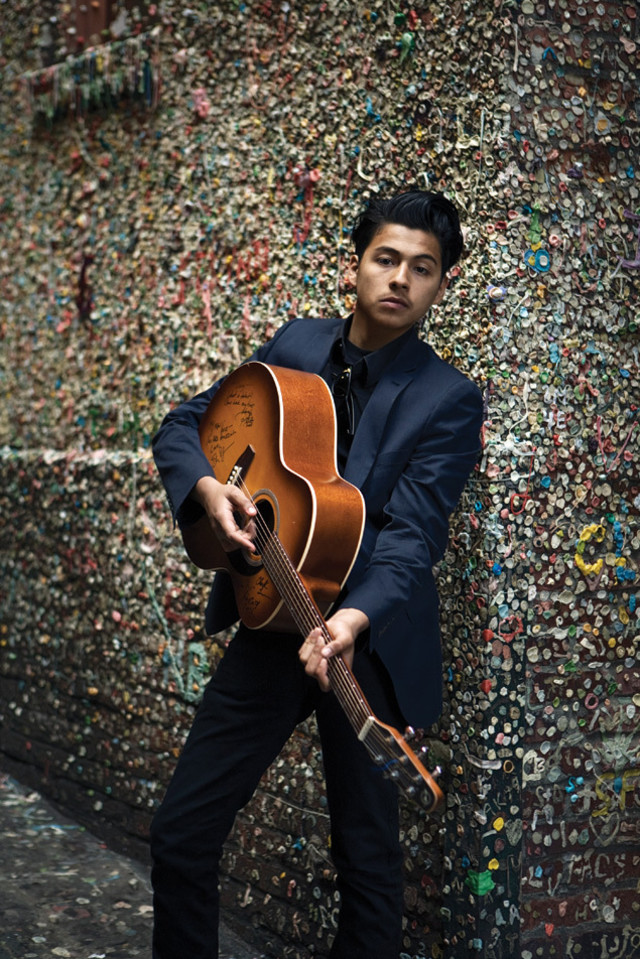

Vince Mira Won’t Walk the Line

Image: John Keatley

THERE WAS A MOMENT in September 2007 at the Cash Cabin, the studio built by the late Johnny Cash outside Nashville, when everyone froze. In the room were musicians intimately tied to Cash and his music—his son John Carter Cash, his bass player Dave Roe, and Jamie Hartford, who played guitar in the Cash biopic Walk the Line. Vince Mira, the Federal Way teen flown in for the recording session, had just crooned the last line of his “Cold Hearted Woman,” a twangy harangue against a cruelly apathetic succubus (“…as far as you are isn’t far enough for me”), leaving his audience speechless.

Finally, Hartford, who’d been scribbling music dictation in a notebook, dropped his pen and paper and turned to the producer. “John. Carter. Cash. Does that freak you out?” John looked up, “Yeah, that freaks me out.”

John Carter had just heard a familiar voice pour from the mouth of the teenager. The producer had agreed to record an album with the talented teen—already making a name for himself with Cash covers—on the condition that “We don’t just record a bunch of my dad’s old songs.” Now, here was Mira performing an original, but his voice, a haunted baritone, was spot-on Johnny Cash.

Nearly two years, an EP, and an album later, Mira’s been heralded by local and national media as some sort of multicultural reincarnation of the Man in Black. He draws crowds wherever he performs—the Sasquatch! Music Festival, Bumbershoot, the Can Can Cabaret club. Success is sweet for the shy teen from the suburbs. But can he make the leap from novelty to bona fide music star?

If that question is on the mind of the audience at the Can Can, where Mira performs every Tuesday, no one’s showing it. On stage—any other night of the week the site of sex-charged vaudeville—Mira tunnels through to the next Johnny Cash tune like a locomotive groaning past a company town. “I got great big blisters on my bloodshot eyes from looking at that long legged woman up ahead,” he sings, mouth darting around the microphone like a teenager gathering courage around the lips of his first girl. Head crowned with jet black pompadour, body sheathed in a tight black suit, white shirt cuffs exploding at the wrists, the 17-year-old troubadour strums his Gibson and wails on: “And ever since she started running round from bar to bar I just can’t eat a bite or keep my stomach settled down.”

The crowd—shaggy twentysomethings with hands stuffed in their peacoat pockets, conventioneers steered to the Can Can by concierges with a flair for shocking out-of-towners, a pear-shaped dad elbowing his daughter every time a familiar honky-tonk song begins—is like a 56-person sound system programmed to say Oh my god and Are you kidding me every 11 seconds, a reaction that’s more disbelief than pop-cult critique. And in between songs: “Play ‘Cocaine Blues’!” “Play ‘Ring of Fire’!” “Walk the Line!”

“We’re working on getting away from the whole Johnny Cash thing,” Mira said in the dressing room a few hours earlier. Sitting in the cabaret dancers’ tangled lair, which bursts with boas and sequins and smells vaguely like a clothes hamper, Mira fixed his gaze on the ground, lifting his coal-black orbs to press a point. “I have my own songs,” he said, vowels sliding off into an accent acquired in a Spanish-speaking home. He’s shyer around strangers than his powerful and confident stage presence suggests, giggling to fill uncomfortable silences. And he says “man” a lot—as in, “Yeah man, it’s an honor”—a habit likely picked up from hanging with musicians two, three times his age.

Son of a Mexican father and a Native American–Italian mother, Mira’s been shaped by a patchwork of cultures, but the one that influenced him most was the Los Angeles punk and rockabilly scene of his two older brothers, both more than a decade his senior. Before moving to the Northwest, the family lived in LA and San Antonio, where the brothers fed his adolescent ears a steady diet of Social Distortion, the Cash-inspired punk band. When he was 11 his mother bought him a guitar, which his future brother-in-law, Daniel, taught him to play. Together they performed for the family, mostly Mexican ballads, but also Johnny Cash songs, with Daniel singing and strumming and the 11-year-old apprentice playing backup. “My brothers are big fans of Johnny,” Mira said. “He’s different from everyone else. There’s a lot of people who sound like the Beatles. Or Elvis. But nobody sounds like Johnny Cash.”

Nobody, that is, except Vince Mira. It’s a touchy topic. “We still do Johnny Cash songs for the fans who want to hear them.” But, he admits, channeling the Man in Black has brought him far.

One minute he was 14-year-old Emmanuel Miranda, trying to transition from a San Antonio private school into Todd Beamer High in Federal Way—“Is everything okay with your son?” the school counselor had asked his mother, Lupe. “He never talks to anyone and he eats alone”—and on weekends accompanying Daniel on guitar in Pike Place Market. The next minute he was a solo busker—Daniel got a job—picking through mostly easy-to-ignore Beatles and Spanish folk tunes. But when he sang “Ring of Fire” he stopped Market patrons in their Crocs. You sound just like …. And the tips got bigger, up to $100 an hour. Do you know “Folsom Prison Blues”? “No, but I’ll learn it and know it next time.” By the time he turned 15 he had learned a handful of Johnny Cash songs.

Image: John Keatley

Neither Emmanuel nor his mother—whom Market officials required to accompany the underage busker when he performed—could’ve guessed that the stranger who approached them on a cold Saturday in April 2007 would change their lives. Nor could they guess that the man, who identified himself as Chris Snell, had an alter ego: Herr Doppelganger, master of ceremonies at the Can Can, where in rubber wig, big-ass Elvis sunglasses, suspenders, and oversize tie—a cross between Martin Short’s hypernerd Ed Grimley and Joel Grey’s oily showman in Cabaret—he bellows from the stage, introducing the Can Can Castaways, the in-house quartet of burlesque dancers, Faggedy Randy, Fiona Minx, Jonny Boy, and Rainbow. Snell, a classically trained opera singer and longtime LA concert promoter, bought the Patti Summers Lounge in 2004 from the eponymous Seattle jazz singer and turned it into the Market’s most poorly kept subterranean secret, a red-lit cavern draped in purple and host to surrealist French entertainment, which attracts, much to Snell’s secret chagrin, “A lot of ladies-night-out parties.”

Snell was walking to work on that cold Saturday when, as he was about to descend the stairs into the Can Can, he heard it: “I hear the train a comin’, it’s rolling round the bend.” What? That sounds like… But… There on the sidewalk in front of Left Bank Books was a Latino kid sitting on a milk crate, his small frame wrapped around a guitar, working his fingers over the strings, and singing, “I ain’t seen the sunshine since I don’t know when.” “Is this your son?” Snell asked Lupe. “Would you two mind coming downstairs?”

The next day the 15-year-old climbed on stage and ran through his repertoire for Snell and his artistic advisors, Rainbow and Jonny Boy from the Can Can Castaways. He was nervous. He sang to the floor and rushed into one song after another. “Out on the streets people just walk by, and some don’t listen and some do,” the singer later recalled. “But with this you’re playing for people and they’re going to listen. It’s nerve wracking.” But that voice… Snell and his team exchanged glances. They wanted Emmanuel in their weekly variety show, I See London, I See France. But the kid needed a name, something as compelling as Herr Doppelganger and Faggedy Randy.

“Juanny Cash” played for his first crowd a few weeks later. But Juanny sounded so much like the real thing that Snell suddenly had a problem on his hands. His email and voicemail were flooded with accusations that he was exploiting a young kid with a gimmick. “Basically, they accused him of lip-synching.”

So the next time he had the singer on stage Snell tried something different. “Ladies and gentlemen, back, due to popular demand, Juanny Cash! However, last time he was here, everyone said that he was lip-synching. So we’re going to do a little test here. All right Juanny, what I’m going to do is, every time I tell you to stop singing, I want you to stop, and we’re going to go through this a few times, just to prove to everybody in this crowd you’re not lip-synching.” The teen would start, “Love is a burning…” Stop! “I fell into a ring…” Stop! “And so we did this back and forth thing for a little while,” Snell recalled, “and then people realized it was no BS.”

By June, Juanny had his own Tuesday show at the bar. But Snell had bigger ideas for his newest act. For several months he tried to reach Cash’s son, famed producer John Carter Cash. He sent some 50 emails, all ignored. “Of course I gave him this sob story,” Snell recalled. “‘You’ve got to help this young kid out, man, he’s the right guy,’ da da da.” Finally John Carter requested a demo. He liked what he heard on the demo but before he would produce a record he wanted Emmanuel to come up with original material.

Fine with Snell. That was his plan all along. He enlisted local singer-songwriter Michael Vermillion to work with Emmanuel. They came up with a handful of songs by “Vince Mira,” the easy-to-remember name they all brainstormed and voted on.

Mira, Snell, and Lupe joined John Carter for a week in September 2007 at the Cash Cabin. Along with Cash bassist Dave Roe and Walk the Line guitarist Jamie Hartford, Mira recorded original material, including “Cold Hearted Woman,” Vermillion’s soulful “Lonely Heart,” and—in Spanish—Cash’s “I Walk the Line” and “Ring of Fire.”

After that events unfolded like the jump-cut sequence in a Hollywood flick about a rising star. Snell flies home to Seattle, runs to a bar near the Can Can and plays the recordings for friends, one of whom works at KOMO TV, which features Mira on the five o’clock news. Then—the vignettes shorter now, the transitions choppier—a Good Morning America producer sees the news spot, calls Snell, invites Mira on the show. In November Mira, Lupe, and Snell fly to New York, where a live Good Morning America audience (cooing girls melting at the knees and all) gasps at the Boy in Black in faux-Western attire blazing through “Ring of Fire,” while 4.2 million home viewers lose their collective Cash-loving minds. Jump to later that same day at a bar in the East Village, where Snell checks the voicemail on his BlackBerry: “Hello, this is the Ellen DeGeneres Show.”

Mira does Ellen. He befriends Pearl Jam’s Stone Gossard, who invites him on tour. The Tuesday crowd at the Can Can grows into a fire marshal’s nightmare. Life at Todd Beamer High School changes, too. The students, at the time swept up in the media circus surrounding another fellow classmate, American Idol finalist Sanjaya Malakar, crowd Mira, all wanting to be his friend. He starts lunching in the principal’s office to get away from all the attention. But it’s still too much. Lupe takes him out of Todd Beamer, signs him up for an online correspondence school. He plays festivals, including Sasquatch, performing his expanding repertoire of originals.

And everywhere the crowds couldn’t get enough—of Johnny Cash incarnate. They kept clamoring for the cover songs. Worse, fans and the media still referred to him as “Juanny Cash.” “I cringe every time I hear that name now,” Snell confesses. Snell’s plan had worked too well. Mira’s star was, it seemed, inexorably tied to that of the legendary singer.

Questions emerged—in comments attached to Mira clips on YouTube, whispers in the stairwell after shows—“Talented kid, but what next?” Would Mira become anything more than a Vegas-style lounge act on par with El Vez, the longtime Latino performer who channels Elvis Presley?

Snell regrets sticking his top act with the unshakable “Juanny Cash” sobriquet, but suffers no qualms about pushing the Boy in Black meme early on. “You want media attention. Do you tell Good Morning America no? You have one opportunity to do this, one chance, and you turn it down? I think we probably made the right decision.”

“If I were him I’d never do another Johnny Cash song again.” —Dave Roe, Johnny Cash’s bass player

Dave Roe, the Nashville bassist and member of Johnny Cash’s band, offers some advice: “If I were him I’d never do another Johnny Cash song again,” Roe said. “It’s one thing for people to say he’s reminiscent of Johnny Cash. But if he keeps doing Cash they’re going to say he’s—if not an impersonator—a tribute artist at the very least. I don’t see any way out of that other than to refuse to play those songs.”

Though Mira hasn’t taken that suggestion, he dilutes the Cash content in his shows with his own material, including songs from a second album he recorded with Roe at the Cash Cabin last year, ranging from the sweet, sentimental “Closer” to “Mr. Harrison,” a Bob Dylan–inspired salvo against hypocrisy. (Dylan became an increasingly important source of inspiration after Mira saw him live in Nashville.)

Next for Mira is a third session later this year at the Cash Cabin, where he’ll record another slew of original songs, a performance at Austin City Limits music festival in October, and—proof that Mira and Snell are reluctant to wean themselves off the Cash cow—a possible commemorative Folsom Prison concert next year when the singer turns 18.

“The next time somebody hears from us,” Mira insists, “they’ll say, ‘Hey, it’s Vince Mira,’ not ‘Hey, that kid that plays Johnny Cash songs.’”

Back in the Can Can dressing room on a recent Tuesday, Mira stood before the mirror sculpting his pompadour until it looked like the fin on a midnight-black ’57 Chevy. His mom sat off to the side, looking at his reflection. Lupe’s concerns have nothing to do with her son’s Johnny Cash problem. Record labels have approached Mira, yet Lupe has urged turning the offers down. “I don’t want this to get too big too fast,” she said. “He’s too young.”

A few minutes later Mira could be heard outside the dressing room, up on stage, picking through the opening chords of Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” Lupe struggled with one last question. Where’d he get it? How did this happen to your shy son? She searched for an answer but was distracted. One of the most beautiful voices she or her questioner ever heard filled the dressing room. “Ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe.”