Can We Finally Fix 99's Problems?

According to an SDOT study, 17 percent of Seattle's traffic fatalities happen on Aurora. Pedestrians were involved in just 5 percent of collisions on the roadway, but account for half of those deaths.

Image: Chona Kasinger

Linda Julien keeps a count in her head. The walk light at the intersection of Aurora Avenue and North 130th Street lasts 30 seconds. Right now Julien can make it across in 28. The 74-year-old learned how to use the timer on her cell phone to confirm this.

“I have a few years left before I can’t make it,” she says. Some of her neighbors at Bitter Lake Manor senior housing aren’t fast enough. “People with wheelchairs in particular.”

The retired bookkeeper crosses Aurora on foot to catch the RapidRide E Line bus or to shop at the Asian Family Market or PetSmart. Julien doesn’t have a car—“I try to use errands as a way to get out and get exercise.” She knows which parts of Aurora have more sidewalks and fewer driveways where cars might not see her as they pull into and off of the thoroughfare. She knows to swivel 360 degrees to monitor traffic visually, since she doesn’t always hear so well. She knows she’s a person moving slowly through a space that prioritizes hulking, fast-moving vehicles.

Seventeen percent of Seattle’s traffic deaths happen on this 7.6-mile stretch of road. Thirty of Aurora’s city blocks lack sidewalks, putting pedestrians dangerously close to cars. It’s hard to find another major arterial with such long distances between crosswalks. As a result, pedestrians often dart across the six-lane roadway.

Roads, like people, are bad at multitasking. Aurora Avenue has long held two identities: A high-speed thoroughfare designed to get drivers from one part of town to another, and an urban street filled with businesses and driveways and pedestrians running to catch the bus. It fails at both.

Aurora Reimagined Coalition members Lee Bruch (left) and Tom Lang sport their "99 Problems" T-shirts from a previous ARC campaign. Crossing the street safely is definitely one.

Image: Chona Kasinger

Tom Lang keeps a timeline in his head. A tragic one. The woman who died when a car struck her wheelchair as she crossed Aurora Avenue, legally, back in 2002. The brother and sister visiting from Los Angeles in 2019, hit and killed by a driver under the influence while they were walking to visit the Fremont Troll. The University of Washington student running on Green Lake’s outer trail just two months earlier when a car jumped the curb. She survived, but with life-altering injuries. There are many more.

Lang and his wife bought a house two blocks from Aurora Avenue in 2019. Now, when he visits nearby Pilgrim Coffeehouse, he trundles his young daughter across the aging concrete pedestrian bridge, itself an attempt to overlay an urban pedestrian reality onto a landscape very much built for cars.

Lee Bruch’s memory harbors another list: of missed opportunities. The early-2000s study on corridor improvements, squashed by objections from business owners (Shoreline completed its stretch only after going to court). The 2015 Move Seattle levy that listed Aurora as a priority, but the immediate funds went elsewhere once voters approved it. A few years back, the Washington State Department of Transportation re-paved a significant chunk of Aurora, effectively upholding the status quo rather than using the maintenance as a chance to make safety improvements.

That’s when Bruch, a retired architect, cofounded a community group, the Aurora Reimagined Coalition, seeking momentum for change that makes it past the reports-and-studies stage. “Aurora has a lot of problems and a lot of people are really upset,” he says.

Last winter, Lang and Bruch each received a surprising phone call in their capacity as ARC members. It was the equivalent of a fairy godmother materializing with a wand—if magic wishes came with stakeholder meetings and environmental impact studies. State senator Reuven Carlyle, one of Washington’s most influential legislators and a stranger to both men, was calling with a question: If I can secure a big chunk of money to improve Aurora Avenue, can you come up with ways to use it? Could they ever.

Carlyle was approaching retirement, contemplating his legacy, and was ready to expend political capital. In the spring of 2022, governor Jay Inslee signed the $17 billion Move Ahead Washington package that included $50 million for Aurora Avenue. “That’s not the magic answer,” says Carlyle, who retired soon after. “But it is one hell of a down payment.”

The funds came as a surprise to many, as did the unusual language Carlyle used in the bill. Could Seattle at last see genuine change on its most dangerous, most complicated, most history-laden corridor?

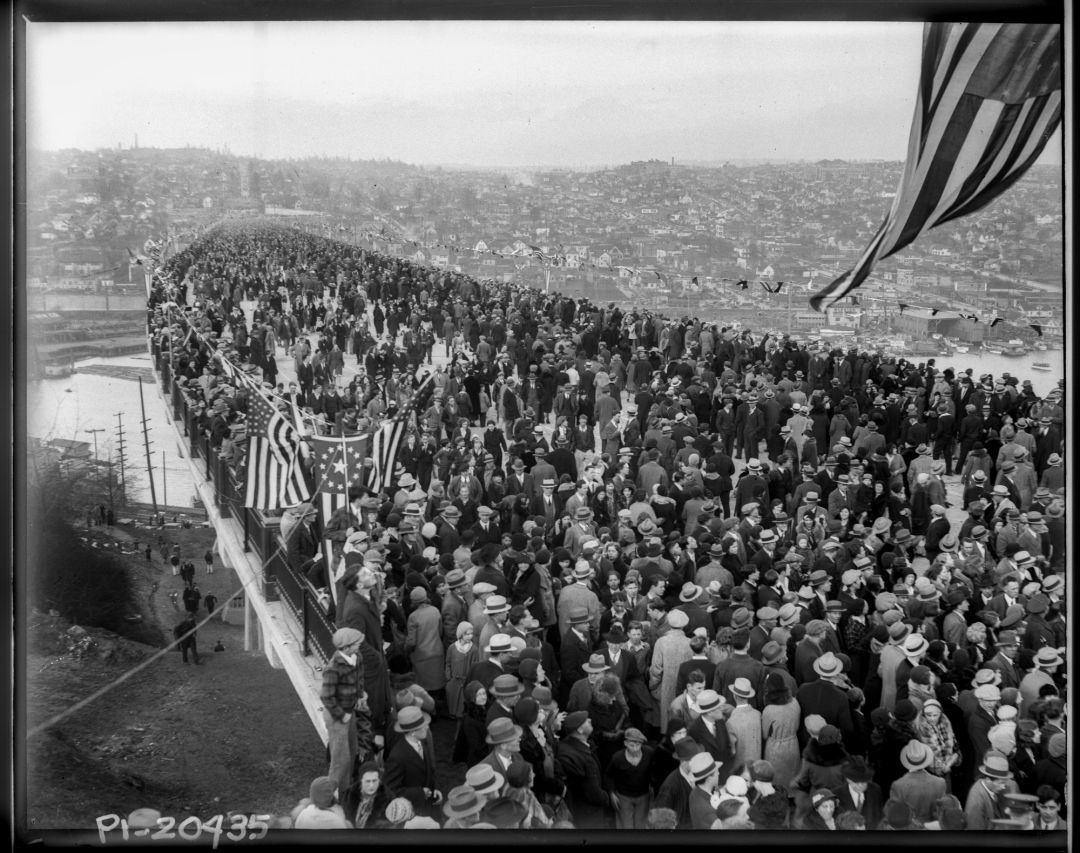

Seattle turned out for the opening day of the Aurora Bridge in 1932.

Image: Courtesy MOHAI

The city chose George Washington’s 200th birthday, February 22, 1932, to dedicate the new bridge that soared 155 feet above Lake Union. President Herbert Hoover pressed a golden telegraph key back in Washington, DC, that ignited a siren on the bridge and a 21-gun salute in the water below. The Aurora Bridge was the final link in the Pacific Highway, which stretched from Mexico to Canada. It cemented Aurora Avenue’s status as Seattle’s major north-south thoroughfare—at least until Interstate 5 arrived three decades later.

Today, Aurora is a state highway surrounded by city. Six lanes of high-speed traffic race past used car lots and auto repair shops, a relic of the days when these were the outskirts of town. Midcentury car culture is visible everywhere, from the stores isolated by large parking lots to the run-down motor inns that once lodged travelers headed to the World’s Fair.

But Seattle’s modern-day identity is present here, too. Recent up-zoning measures have meant new apartment buildings along the corridor, bringing more residents and a need for more neighborhood-style businesses. King County Metro’s busiest transit line, the RapidRide E Line transports more than 10,000 passengers a day on Aurora.

The $50 million from the state came with unusually specific stipulations. Carlyle’s language concentrates the money in a 15-block stretch—North 90th to North 105th streets—in the Licton Springs neighborhood. The senator’s main goal, he says, was “avoid the money being peanut buttered.” That’s legislative speak for spreading funds over a lot of different needs (a sidewalk here, a leading pedestrian interval there). “Fifty million will evaporate into thin air if we spread it out over 10 miles,” says Carlyle. “My goal was to radically transform a small area at the highest-quality level.”

He hopes those blocks will illustrate what’s possible, even if the state won’t actually allocate the money for at least another few years. Additionally, the Seattle Department of Transportation needs to have a big-picture plan in place first. You can’t just rebuild one small section of a street when you’re talking about drainage systems and lane realignments that will impact all of it.

SDOT Director Greg Spotts got involved with Aurora Avenue even before his first official day on the job in September 2022. Constituents contacted him about some healthy trees in danger of removal due to sidewalk improvements (insufficient tree canopy is one of the corridor’s many issues), even though Spotts was still living in Los Angeles at the time.

“I haven't met anybody who's happy with the current state,” he says. “There's no other corridor in Seattle where no one will stand up and say, I like it like this.”

In 2021, SDOT began a state-funded study of Aurora Avenue, examining the entire stretch from Harrison Street up to the city limits at 145th Avenue; various agencies have contributed funds for improvement. But the roadway’s alter ego as State Route 99 complicates matters. WSDOT controls everything from curb to curb (not that Aurora has nearly enough actual curbs), while SDOT manages sidewalks (also in short supply) and beyond. Throw in King County Metro for the Rapid Ride bus line and Seattle Public Utilities for drainage issues. That’s a lot of signoffs.

State roads, by definition, “usually prioritize the mobility of traffic,” says Ray Delahanty, a transportation planner (and North Seattle native) who runs the CityNerd YouTube channel. “They’re hands are often tied by the history,” not to mention the legitimate need for a backup route if I-5 has any issues. Planners like him describe Aurora as a “stroad,” a portmanteau of “street” and “road.”

SDOT has already gathered input from the public on everything from bike safety to crosswalks. The agency could release a few potential plans for the entirety of Aurora by this fall. Then it’s vet, analyze, rinse, repeat, until an optimal plan emerges…then receives the additional scrutiny required for any federal funding.

It’s way too early to say when actual construction might begin. But thoughtful modern infrastructure—whatever that ends up looking like—could address issues beyond safety and traffic deaths. As Spotts sees it, “The streetscape is so hostile to people, that we're not getting the value that we need out of that land for the economic growth and housing development that we need in Seattle.”

This round of plans and promises feels more real than anything longtime activists like Lee Bruch have witnessed in the past. Linda Julien already sees new neighborhood residents waiting to catch the bus downtown. Someday, the Aurora they know could be a place where you can cross the street without a thought.