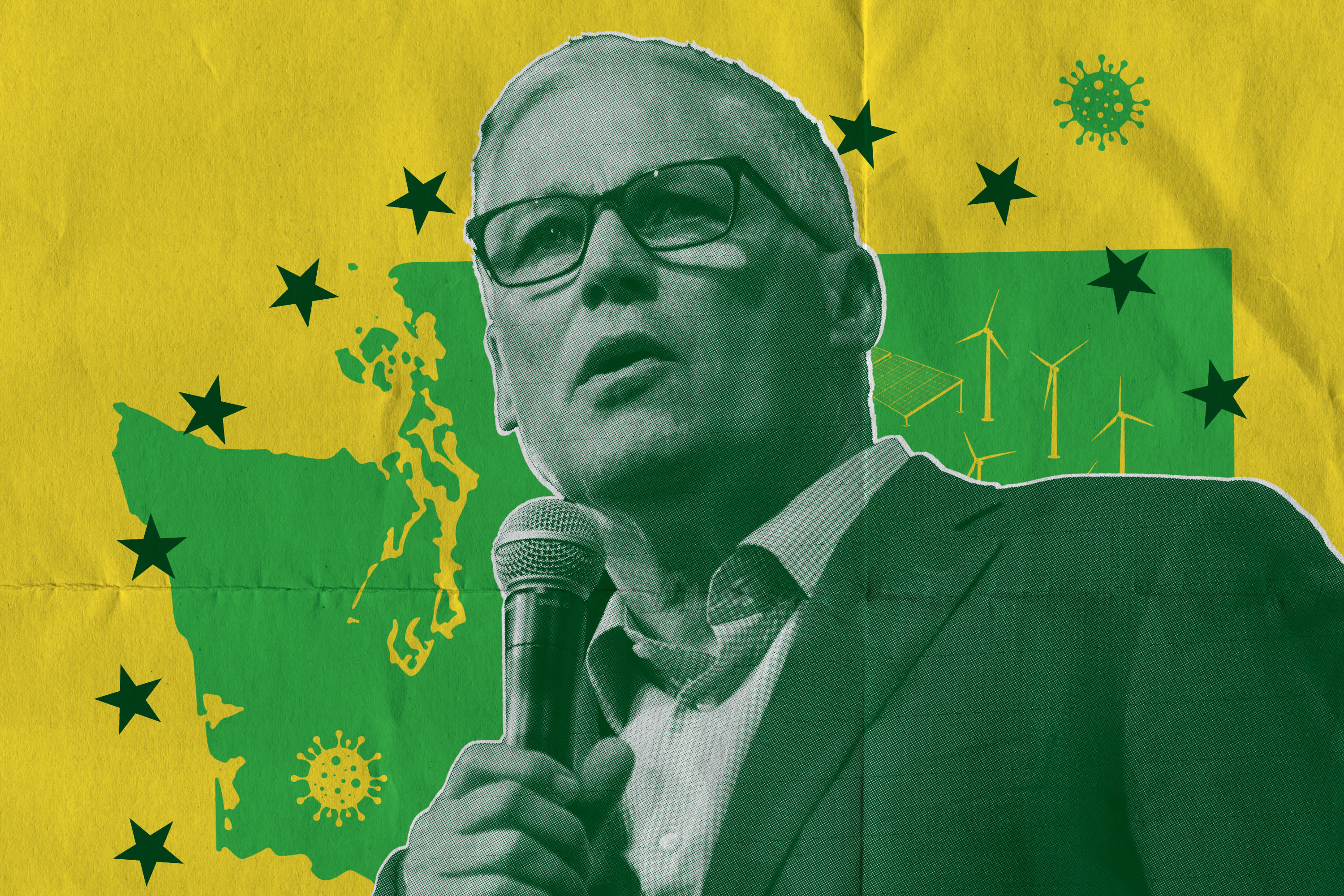

Why Jay Inslee Chose to Stay in This Washington

Seattle Met composite, Inslee portrait courtesy Gage Skidmore

Jay Inslee’s on my screen again, but this time he wants to talk about Kon-Tiki. It’s January 22, one day after one year since the first confirmed case of Covid-19 in Washington, since the governor’s press conferences became appointment viewing for more than just journalists and wonks. From a high-backed chair at a mahogany table inside the state Capitol, he’s rendered verdict after verdict on the public’s ability to sit at restaurants, to see friends. His didactic guidance provides a rare injection of monoculture (“Washingtonians”—drink!) into a dispersed, shut-down state. Now he’s in a different seat—in the dining room of the governor’s residence—as he wedges an interview between briefings and his first shot of a coronavirus vaccine. Over his right shoulder, there’s a mirror and a couple of sad-looking candles. Over his left, there’s a bookcase with…well, I can’t quite make out the lettering on the bindings from this virtual view. “Let’s see if there’s a good one,” Inslee says, swiveling. His gaze settles on Kon-Tiki, Thor Heyerdahl’s epic travelogue, which I haven’t read. “Ohmygosh! It’s one of the most classic adventure stories of all time.”

The short version: A dubious colonization theory prompts some guys to float from Peru to Polynesia on a raft made of balsa logs. They encounter rogue waves, sharks, whales. A parrot dies. But they make it. “They were just insane,” Inslee says in admiration.

He keeps scanning until he comes across another book that’s a personal favorite—his own. Published in 2007, Apollo’s Fire trumpets a clean-energy economy that will harness the environment’s natural forces to help save it. Inslee, a congressman when he co-authored the book, shares stories of going toe-to-toe with Big Oil backers George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. While working on it, he spoke with luminaries like solar cell pioneer Jimmy Carter, whom he’d talked to about a new green Seattle high-rise the day before our call.

Copies of Inslee’s book are hard to come by these days—really good or really bad news in the publishing world, I remind the governor. He’s less chipper now. “It was bad news in our case.”

Lights, Camera, Shutdown!

Before Inslee delivers his coronavirus announcements, staffers scramble to prepare slides for his data-heavy speeches.

Jay Inslee’s a persistent fellow. For decades, he’s harped on combating global warming even as progress toward lowering greenhouse gas emissions has proceeded at the pace of a makeshift vessel bobbing across the Pacific. He staked a short-lived presidential campaign to the cause, decrying Joe Biden’s climate plan on a crowded Democratic debate stage in July 2019. “Our house is on fire!” he hollered, sounding appropriately desperate for an existential call to arms. Some fawned over his Clark Kent glasses and jawline as he vowed to save the planet (“Horniness for Jay Inslee Is a Renewable Resource,” one New York headline read). Still, his plea didn’t move the polls much. Three weeks after his 15 minutes on the national stage, he dropped out. “I would have preferred to win,” Inslee tells me, laughing. Vindication would come, however, when Biden tweaked much of his environmental agenda to Inslee’s liking: “He’s been a house on fire!” says Inslee, finding new use for his debate line.

Many pundits expected the governor to join the president’s administration in a climate-related role. But Inslee didn’t seek a place in the cabinet, he told me, and he was never offered one.

Instead the spry 70-year-old decided to stick around in this Washington, the state his family has called home for seven generations. The state that elected him for an almost unprecedented third term this past November. The only other person to hold the governor’s office for that long consecutively is Dan Evans, a Republican who exited Olympia in 1977.

Inslee’s victory seemed like a foregone conclusion after effectively steering the state through the early waves of the pandemic. The messaging on climate change that had failed to galvanize the nation during his presidential run—earnest, science-driven, a bit hokey—had persuaded most of his fellow Washingtonians to mask up and stay away from each other.

Still, the governor had wielded broad executive powers to bend his state toward science early in the pandemic. For all Inslee’s boasting on the campaign trail about Washington’s thriving green economy, the state had only just begun to act with his desired urgency on climate change amid annual legislative slogs. For the bulk of his first two terms, major environment bills went nowhere as the state’s greenhouse gas emissions figures crept upward.

But as Inslee’s book points out, with every crisis comes opportunity. And so it was, on the eve of his third term, that the governor would make his most convincing case yet for his scientific creed.

David Postman wouldn’t touch the grapes. It was the morning of March 8, 2020, and inside a King County government building in downtown Seattle, politicians and public health officials from different parts of the state had crammed into a conference room to discuss the nascent spread of the novel coronavirus. The mysterious respiratory illness had already killed at least 17 people in the Seattle area, including 16 tied to a long-term care facility in Kirkland. Inslee had declared a state of emergency in late February, but social distancing mandates weren’t yet in place. The Sounders had just played in front of a crowd of 33,000. Nobody wore masks yet. Communal snacks and Starbucks may have still seemed appropriate. But the governor’s chief of staff was wary.

Inslee’s top lieutenant would only grow more uncomfortable as the meeting went on, as health experts shared slide after slide detailing the virus’s mushrooming transmission. Within a week Washington could see 5,000 cases if it didn’t impose restrictions, a model showed; at that time, fewer than 200 cases had been reported. Toward the center of the long table, Postman pushed his seat back against the wall, distancing himself from the governor and the CDC representative flanking him. “It really had that feel of everything is changing right here, right now, this meeting,” says Postman. “It’ll be different.”

At his side, Inslee listened to public health officials discuss school closures and other measures. He wasn’t doctrinaire about following the science; what the public will accept is “always a part of the equation,” he says. After the meeting, he convened a small group that included Postman, deputy chief of staff Kelly Wicker, and secretary of health John Wiesman to talk strategy. “That’s where he started to say, Okay, what are we doing? What are we doing? I want to go. I want to do it now,” Postman recalls.

Lockdown wouldn’t happen immediately. Outreach to cities and local health departments would have to come first, to get everyone behind a science-led approach. “I won’t say that there was unity,” says Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan, “but we really believed it was important to speak with one voice and to have the same rules.”

By Wednesday, the same day the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, Inslee had banned gatherings of more than 250 people. By the following Wednesday, he’d shuttered schools, restaurants, and bars. And less than a week later, he delivered his seminal “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order, which clamped down on all social and economic activity in the state beyond only what his administration had deemed most essential.

It wasn’t the country’s earliest mass shutdown—California governor Gavin Newsom, for instance, declared his on March 19—but it would prove to be one of its most effective. Cases across the state went from doubling every four days to nearly every 32 days in the weeks after Inslee’s measures went into place—the fifth-greatest transmission rate drop of any state, according to a study published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases. By April 15, instead of 70,000 cases as officials once feared, there were just under 11,000.

If it were just him, Inslee told me, he probably would’ve moved even faster to restrict activity. But it’s almost never just him.

To understand the way Inslee governs, says former longtime aide Joby Shimomura, you need to grasp his appreciation for teams.

At Ingraham High School in North Seattle, Inslee quarterbacked a powerhouse football squad and came off the bench for the Rams’ undefeated state championship basketball team during his senior season. On the final play of the 1969 title game against Hoquiam, Inslee recovered a loose ball as time expired and hucked it toward the rafters, hugging teammate Steve Waite in a moment captured in The Seattle Times.

The player who snagged the ball after the celebratory fling, Steve Merkley, remembers Inslee as a defensive stalwart. Not a star, but a good role player—someone who meshed with an experienced, cohesive group.

Unlike nearly everyone else on the team, Inslee hadn’t grown up playing in the neighborhood. His early life itinerary followed the scholastic career pursuits of his father. Frank Inslee was a biology teacher, counselor, and basketball coach at Garfield and Chief Sealth high schools before his ascension to Seattle Public Schools athletic director. His wife, Adele, worked in sales at Sears and Nordstrom. Frank’s passion for sports rubbed off on Jay and his younger brothers, Frank Jr. and Todd, who played on the courts and fields near their homes—first in White Center, later in the vicinity of Carkeek Park.

Team Captain

Inslee weighed just how far he could follow the science with public health officials and politicians in the days before this press conference on March 11, 2020. “He didn’t pretend to have the answers,” says King County executive Dow Constantine (third from left).

The move north meant Inslee arrived at Ingraham as an outsider. Sports greased his transition. Though Inslee spent much more time with his future wife, Trudi Tindall, than with the “numbskulls” on the team, former teammate Merkley says “everybody was kind of Jay’s friend.”

In government, former and current staff members stress, Inslee takes a liberal approach to team building. He seeks input from a wide range of government staffers, sometimes forgoing the chain of command. He’s not just an affable jock, as he’s often branded. He likes to poke and prod—to debate.

It’s this expansive approach that appealed to Joby Shimomura in 1996 when a quick coffee with Jay and Trudi at Uptown Espresso in Lower Queen Anne turned into an hours-long discussion about Washington’s future, about her life. They’d ask her to manage his first campaign for governor that year.

Inslee would finish behind Seattle mayor Norm Rice and eventual winner Gary Locke in that race, but Shimomura would soon work alongside him in the U.S. House of Representatives and, later, in the governor’s office as his chief of staff, among other roles. She watched as he responded to catastrophe after catastrophe over the years: the Skagit River bridge collapse, the Oso mudslide, and 9/11. On that day, almost immediately after the Twin Towers were struck, Inslee called Shimomura into his DC office and told her he was shutting it down. There was no time for debate with the team on this occasion; staff were to gather their things and retreat to a colleague’s home nearby. As Shimomura walked out of the government building, she could see smoke billowing from the Pentagon, the site of the third strike. “In crisis situations,” she says, “he just acts.”

Dr. Kathy Lofy had dialed into plenty of meetings since the coronavirus outbreak surfaced in China, but this was a new one for the state’s public health officer: “You need to be on the call with the governor and Dr. Fauci.”

In the early weeks of the pandemic, while president Donald Trump’s administration muzzled the country’s health brass, Inslee called some of these officials to figure out what was really going on. Anthony Fauci, the coronavirus czar seen snickering behind Trump at a White House presser, lent his perspective, as did a World Health Organization investigator who’d been on the ground in Wuhan. Experts advised him that the state would have to impose a shutdown as soon as possible to stave off mass mortalities. “If you’re uncomfortable doing that, it’s probably the right thing to do,” recalls John Wiesman, then the state’s secretary of health, of the guidance.

Beyond the global scientific community, Inslee turned to Washington’s booming “knowledge” industry for counsel. A statistical modeling geek squad that briefed the governor on Friday mornings included representatives from Microsoft, the Institute for Disease Modeling, and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. The group’s findings helped inform decisions like whether to close schools. Later on, Inslee marshaled Seattle’s private-sector brainpower to expedite vaccine mobilization after a plodding start. Starbucks, Microsoft, and Kaiser Permanente were among the first major local employers to lend tech and operational support to mass vaccination. “You will get your reward in the afterlife,” Inslee quipped at a January press conference.

The governor still leaned on morning briefings with local public health officials as he weighed which direction to turn the dial on the state’s activity. Before bed he’d read studies published in The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine to prepare for meetings both planned and unannounced. When news broke about the coronavirus variant stemming from the United Kingdom last winter, he gave Wiesman an impromptu ring on a Sunday morning. “There are times where he’s a real pain in the ass about details and when he is doing all this research, and you’re like, Would you just stop for a moment?” says Wiesman, now a professor at the University of North Carolina. “But you know, that again comes back to: He cares. He wants to know the science.” Some in his state, it would turn out, did not.

A gun jammed into his jeans, Robert Sutherland stood atop a bench outside the state Capitol, clasping a microphone. A tightly packed ring of protesters had formed around the state representative on a hazy Sunday in April of 2020. “Don’t Tread on Me” and Washington Three Percent flags waved behind him; in his line of sight, “End Inslee’s Tyranny” and “Inslee Sits Down When He Pees” signs danced above the crowd. The Republican official from Snohomish County lambasted the governor’s use of his emergency powers during the pandemic. “We’ve warned you, time and time again: back off,” he said, jabbing a finger in the air. “You’re crossing the line of illegal action.”

Hundreds gathered on the sprawling Olympia campus that day to protest Inslee’s ongoing “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order. While the state shutdown had helped curb coronavirus cases, it had also throttled many small businesses and limited recreational activities, like fishing, that seemed safe to many of those in attendance. Their outrage was stoked by president Donald Trump, who’d urged his supporters to “liberate” restricted states even with coronavirus still wreaking havoc on the nation’s health. In Olympia, one of his longtime foes seethed. “The president is fomenting domestic rebellion and spreading lies,” Inslee tweeted two days before protesters defied his ban on large gatherings.

The governor and Trump had sparred, both directly and by proxy, for months. Inslee fired off a social media missive in February after a call from vice president Mike Pence. “I told him our work would be more successful if the Trump administration stuck to the science and told the truth.” Trump responded by calling Washington’s governor a “snake” and “a nasty person.” Inslee’s Twitter shots contradicted his own advice from a famous square-off with the president: During a meeting of the National Governors Association at the White House in 2018, Inslee stood up and told Trump he would benefit from a “little less tweeting.” Now Inslee was the one needling on the social media platform. “There’s something unseemly about such exhibitionism when a pandemic is slipping through your state’s front door,” a Tacoma News Tribune editorial opined.

Reveling in the afterglow of Biden’s inauguration, Inslee didn’t want to discuss his former Oval Office rival during our January interview. Still, he kept alluding to Trump (“unlike some, I want to recognize he beat me fair and square,” Inslee said of his loss to Biden). He’s done the same in public appearances.

To some degree, Trump makes for a convenient Inslee adversary; sparring with him raises the politician’s profile and distracts from other critiques. In January of 2021, after the state unveiled a regional reopening plan based on change-over-time data, rather than static case and hospitalization tallies, a group of Democratic legislators from the Olympic Peninsula wrote that it demonstrated a “disastrous disconnect with the realities of our communities.” Some public health officials even questioned its merit. And as closures stretched into the 2021 legislative session, a bipartisan bill called for the entire state to resume more social and economic activities. Inslee didn’t pretend his recovery plan was perfect. “There are 10,000 legitimate criticisms,” he said during a February 4 presser.

Nor did he shrink in his executive chair as he felt the weight of businesses and schools closing. Gripes with the governor’s far-reaching crisis powers—the state leader can ban just about anything “to help preserve and maintain life, health, property or the public peace” during a state of emergency—weren’t limited to those protesting at the Capitol. Politicians and newspaper editorials implored him to hold a special legislative session over the summer to ferry votes on a state budget shortfall and, perhaps, other Covid-related matters. “During emergencies, sure, the governor can and should issue executive orders, but not for a year,” former Washington governor Dan Evans told me in February.

Unlike Inslee, the 95-year-old centrist Republican whose name graces the University of Washington’s school of public policy and governance was middle-aged when he embarked on the last gubernatorial third term in state history. It was a less partisan time, he noted, though politics has always been “a contact sport.” Neither he nor anyone else could argue with Washington’s pandemic scorecard—only a handful of other states would claim a lower death rate during the first year of the pandemic—but Evans didn’t think the state’s response would necessarily define Inslee’s third term. “The focus is on Covid now,” he said, “but it won’t be for the four years that he’s been elected.”

Along the side of a country road, Jay Inslee—Levi’s, cuffed sleeves, Washington State Cougars mask—stood for a press conference. It was early September 2020, and after so many formal addresses from behind that conference table in the state Capitol, the event conjured a more normal season of election year barnstorming. But something else, something urgent, had drawn the governor out of his quarantine in Western Washington to a small town on the other side of the state.

For weeks, historically rampant wildfires had ravaged the West Coast. On Labor Day they scorched Washington: More acres burned in 24 hours across the state than in any of the last 12 full fire seasons, according to the governor’s office. In Seattle, a scrim of smoke applied a yellow filter to the city. Masks to prevent the spread of coronavirus now doubled as guards against airborne ash.

The situation in Eastern Washington was more dire. Just south of Spokane, fires had destroyed 80 percent of the buildings and homes in the tiny town of Malden. Its post office, its city hall, its fire station—all gone. The governor peered into one disemboweled structure, the brick exterior and charred window frames some of its only remains; other buildings were embers.

In his roadside address, the governor expressed his grief for what had been lost, his admiration for the community’s resilience. Then he arrived at his larger point. “We talk about this as a wildfire,” he said. He raised his shoulders. “I think we have to start thinking they’re more climate fires.”

It was both a gentle overture and a bit of an I-told-you-so. While the governor had been stressing the perils of Covid-19 for months on end, the pet crisis he’d forewarned forever—climate change—had never stopped threatening the state’s future.

Still, even amid so much destruction, the fires’ toll remained less chilling than the pandemic’s scourge. The blazes set off by some combination of rising temperatures and poor land management didn’t bring about mass casualties like Covid-19, just property damage and a notice that global warming could hasten deaths in the future. “It is the perfect problem,” Inslee would later tell me. “It’s slow. The enemy is invisible, which is carbon dioxide. You don’t see its ramifications that day, that year, or maybe even that decade, and it requires a communal response to solve. That’s the hardest thing humans ever have to deal with, so we need the deepest reservoirs of optimism that we’ve ever had.”

During his presidential campaign, Inslee practiced that enthusiasm everywhere from Iowa farmland to a crowded table on The View. He told Joy Behar and company that the country could defeat climate change, that his state had already built a thriving clean-energy economy. He wore an apple pin on his left lapel, a regular feature of his wardrobe that not only advertises Washington’s signature fruit but also ascribes a certain do-gooder quality, to him and his state.

It wasn’t a false pretense. The state had become a leader on renewable replacements for fossil fuels, especially in hydropower. But the broader truth about the state’s progress on the environment wasn’t quite as shiny as the pin over Inslee’s heart when he took that talk-show stage in March 2019—or even when he affixed a similar accessory to a deputy sheriff in Malden on a smoldering September afternoon a year later. Not yet.

Enraging Forest Fires

Visits to communities beset by blazes, like the Sumner Grade fire in 2020, stoke Inslee’s climate change ire.

On matters of climate, says state Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon, “Jay Inslee is impatient for change.” The 34th District Democrat means that as a compliment. Fitzgibbon was one of four legislators in a climate change work group that emerged from the first legislative session during Inslee’s governorship. At his swearing-in ceremony in 2013, the governor, a former state representative himself, declared that he would bring “disruptive change” to Washington. His principal achievement on the environment that year, however, barely made waves.

A new law created a bipartisan work group to devise a strategy for meeting the state’s greenhouse gas emissions targets set in 2008. With its composition split along partisan lines, the group never reached consensus to submit a formal recommendation. Before the bill’s passage, the Senate Energy, Environment, and Telecommunications Committee had even scrapped any mention of global warming. “Whenever you speak in absolutes about the science being concluded,” said Republican state senator Doug Ericksen, then the committee’s chair, “history is replete with people being proven wrong.”

Ericksen, later a Trump EPA appointee, would prove to be a foil for Inslee’s progressive climate plans. So would other legislators, including some Democrats, who told the governor to just hold on a second there. That philosophy didn’t jibe with Inslee. “If you have a huge problem that becomes worse over time,” Inslee told The Seattle Times in 2013, “it doesn’t mean you should start later, it means you should start earlier.”

Inslee’s also risked becoming something of a climate Cassandra to more than just lawmakers. At the turn of this century, when the topic was still novel and Inslee was in Congress, aides worried he’d lose his constituents’ ears. “It felt like a really hard story to tell,” says former chief of staff Joby Shimomura.

Inslee had to listen first. In the mid-1990s, after losing his U.S. House seat in the traditionally Republican Fourth District, he would regularly join a small group of scientists, activists, and others in the back room of a restaurant in Wallingford. They’d eat finger food while discussing concerns about energy policy and the environment.

Inslee has always harbored “a yen for nature,” he says. When he was a child, his parents led youth groups up the flanks of Mount Rainier. They brought Jay and his brothers along to plant flowers and build shelters, including one that still stands near Lake George.

Yet at the University of Washington, he studied not botany or biology, but economics—the foundation for his later focus on creating clean-energy jobs. During a trip to Stockholm in college to study the energy policies of the Swedish city, he admired the double-paned windows in its buildings that cut down on coal-burning heat. He also attended the very first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.

Despite his background, he was mostly absorbing at those meetings in Wallingford, as he often is today. “He’s not an academic in his scientific approach,” says climate policy advocate KC Golden, a frequent attendee of the gatherings. “But he is a scientific enthusiast.”

That passion arrived on Ken Caldeira’s radar in 2005. The scientist partially credited with coining ocean acidification briefed a small group of Congress members in DC about what was then a new concept. While experts had known the sea sucked up carbon dioxide, they weren’t aware it was reducing ocean pH levels to dangerous lows, endangering oysters, clams, sea urchins. At the meeting, Caldeira remembers, Inslee wondered why more people weren’t there, why it wasn’t a higher priority. It wouldn’t be the last time he felt that way in government.

Few things have tested Inslee’s limited reserves of patience, and boundless optimism, like the Washington state legislature. For a law to pass through both chambers and make it to the governor’s desk, it must survive a byzantine system of committees, hearings, actions, amendments, and votes known as democracy.

During the better part of his first two terms, Inslee watched climate bill after climate bill die in Olympia after West Coast peers had enacted similar laws to lower greenhouse gas emissions. A cap-and-trade system like the one passed in California fell flat in 2015. A direct tax on carbon like the one British Columbia instituted in 2008 couldn’t pass in Washington a decade later. A low-carbon fuel standard, already codified in California, Oregon, and British Columbia, got blocked twice by Democrat Steve Hobbs, the Transportation Committee chairman in the Senate. Conservatives almost unanimously resisted these policies. “If we went to an autocracy, and I could just choose my own policies, it would have been a hell of a lot better,” Inslee says, tongue firmly in cheek as he leans back in his chair at the governor’s residence. “But we have a democracy. And I respect democracy.”

The post-2018 setbacks were particularly grating for Inslee, according to former chief of staff David Postman, given the Democratic control of the legislature. Republican opposition was to be expected, but this was his team letting him down. Pushback from Big Oil and squabbles among environmental activists had also led to failures in the legislature and on ballots in November, where a 2018 carbon tax initiative backed by Inslee got rejected.

The defeats created a greater gap between the state’s environmental reputation and its reality. Despite boasting a climate-conscious governor and a burgeoning energy sector, Washington’s greenhouse gas emissions had actually climbed since Inslee took office.

But in 2019, as he embarked on a presidential run, the governor sought smaller wins on climate rather than sweeping economic measures. The strategy yielded a much-needed triumph. Shortly after Inslee visited The View, the legislature voted to transition to 100 percent clean energy—think wind and sunshine instead of coal and natural gas—by 2045. Washington is one of only a handful of states to make that commitment.

Inslee noted that the benefits of this acclaimed electric grid hadn’t kicked in yet when I brought up the state’s rising emissions. It’s certainly true they’ll help. It’s also true the state remains well off the pace of reaching its net-zero emissions goal by 2050 thanks to naggingly high transportation pollution. “We’re way ahead,” says climate activist KC Golden, “and we’re way behind.”

But Inslee’s back to taking big swings on the environment. At this year’s legislative session, he unveiled another suite of climate change policies. A plan to decarbonize buildings died in committee. But after so many letdowns, the waning hours of this year’s lawmaking marathon brought the long-awaited passages of a clean fuel standard and cap-and-trade system. The latter incentivizes polluters to lower greenhouse gas emissions and requires the state to improve air quality in communities “overburdened” by pollution. “We finally have meaningful climate legislation that reflects the values and priorities of Washingtonians,” Inslee said after the session’s close.

Yet, even if all of his proposed policies were to pass, I pointed out in January, the state would still be a little shy of its 2030 greenhouse gas emissions benchmark. “You have to have a plan that will be aggressive enough to fit the needs of the moment,” he explained, “while not so aggressive that no one will follow you.”

Because he’s Jay Inslee, he compares it to leading a peloton. Get too far out ahead of the other cyclists in your pack, and you can’t bring any of them along.

First Teammate

Trudi Inslee, the governor's wife of nearly 50 years, has had a "profound" effect on his decision-making, Jay says. Here she receives a hand at the 2019 State of the State address.

The daffodils are coming up and the plum blossoms are out, Inslee informs me the next time we speak. It’s a Monday in mid-March. He’s just announced an order to return more children to classrooms and an expansion of the vaccine rollout, which has already ratcheted up several notches. Meanwhile, his climate legislation package is making progress in Olympia. “It’s a good time to be alive in Washington,” Inslee says.

He’s sitting in a different dining room this time, working remotely from his home on Bainbridge Island, donning what can only be described as PNW-chic (a fleece beneath a suit jacket). Over one of his shoulders peeks a painting of the Moses Coulee canyon in Central Washington. “We’ve had this for, I don’t know, how long have we had this, Trudi?” Off-screen, his wife answers immediately: 1993, when Inslee represented that rural area of Washington in Congress.

Like many couples during the pandemic, the Inslees have spent more time at home together than perhaps ever before. Trudi’s participated in some government team discussions, including when staffers worked on the governor’s inaugural address video. “The team said, ‘Yeah, you look good there gov, that was OK.’” But Trudi? “Noooo. Not good.” They redid the whole thing.

In the first draft of Inslee’s speech in that video, spokesperson Mike Faulk called it Inslee’s “third and final term.” Inslee did a double take. Final? “Strike that phrase,” he instructed. But he was just being cautious. “I would not bet on me having another term.”

He won’t say if this is his last political stop, if he’ll run again for president. He will say why he stayed. Ditching this Washington for that other one would have meant leaving behind three children and four grandchildren he often mentions in speeches. And with a Democratic trifecta of control in Olympia, he saw an opportunity to move climate change legislation that would protect their future, and Washington’s. Even just a few years ago, environmental bills in Olympia held about as much promise as the Kon-Tiki raft halfway across the Pacific. Now the political currents have shifted.

At the same time, Inslee stresses, he wanted to keep “a steady hand on the tiller” as the state weathered the pandemic’s waves. For though his fitful voyage toward a sustainable future finally has some steam behind it, he has another crisis to see to shore first.