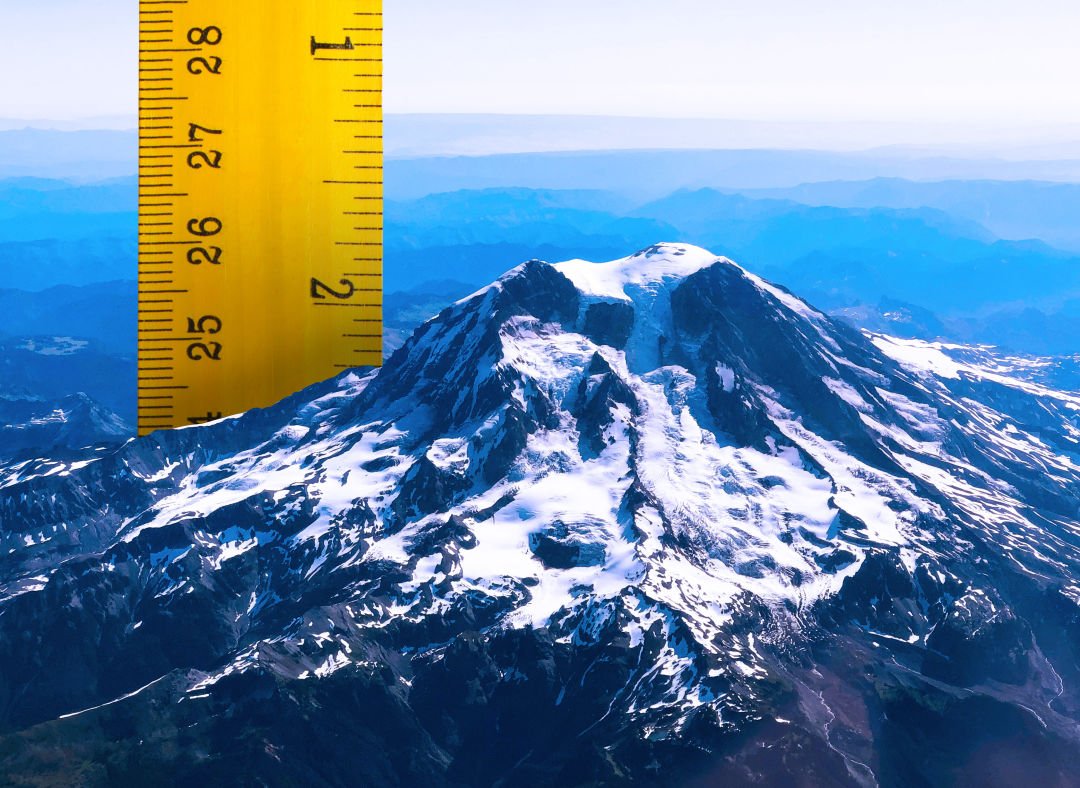

Rainier Is Shorter Than We All Thought

Image: Seattle Met Composite and Peter Hulce/unsplash.com

Hold on to your hat: Mount Rainier isn't what it used to be, and not in a metaphorical sense. Like so many of us, the volcano is shrinking as it ages. But one local scientist and mountaineer just discovered that it got so much shorter that the summit point itself has changed.

On August 27, Eric Gilbertson packed a load of survey-grade GPS units into backpacks and began the climb up the southeast side of Mount Rainier, ascending ladders and crossing chasms of ice. Much of the equipment was borrowed from the Seattle University civil engineering department; Gilbertson is a teaching professor in mechanical engineering there, though this was more of a personal project. Since 2022, he's been measuring the exact heights of Cascade peaks. Last week on Rainier, he confirmed something big.

The exact height of the mountain was first measured by triangulation in 1914, with the number determined in 1956—14,410 feet—still used by United States Geological Survey maps. That's a point called Columbia Crest, a bump of ice to the side of the giant crater that forms most of Rainier's headpiece; it's where everyone goes to take their summit photos, to pose with an ice ax, to catch their breath before the long trip back down.

Image: Courtesy Eric Gilbertson

But Gilbertson, an accomplished mountaineer, heard from friends who work as guides on Rainier that Columbia Crest didn't feel so top-of-the-world anymore. The crater rim, including a part that melts out to rock in the summer, looked higher than the known summit. So early in the morning August 28, Gilbertson and his climbing partner set up their GPS units and took precise readings, double checking them with a site level to measure the angle between the two points. Columbia Crest: 14,389.2 feet. The southwest rim of the crater: 14,399.6 feet.

In short, Rainier is about 10 feet shorter than it used to be, and the summit isn't the summit anymore.

Gilbertson's work isn't official, but then again he doesn't know what would make it so. "It's unclear to me what makes something official or not," he says; his friends at the USGS also didn't know if the agency maintains an official list of summits like this. Using his data, he estimates that the rim overtook Columbia Crest sometime around 2014.

As for the reason behind the big change, Gilbertson notes, "I'm probably not qualified to exactly say why it melted down," but thinks climate change sounds like a likely reason. The last century has seen huge changes on the mountain, with 42 percent of the glacier ice disappearing since 1896. At least one glacier has totally ceased to exist.

Image: Courtesy Eric Gilbertson

Gilbertson is as serious of a mountaineer as he is a scientist; he and his twin are attempting to ascend the highest point of every country on earth, and they're 145 countries into the project. He published his Rainier results on his own blog, written up in the style of a scientific paper, but he doesn't know yet if it will be published elsewhere. His schedule is pretty full; he squeezed this elevation study in between performing the first southeast-to-northwest traverse of Greenland (by snow kite and including four first ascents) and the start of fall classes at Seattle U.

But despite his globetrotting, Gilbertson still has plenty to explore near home. In his Cascade survey project, he has focused on peaks likely to have shifted from climate change, places where there's an ice cap up top (there are four such local spots, including Rainier) or a glacier forms the saddle between high points. He's drawn to combining mountaineering and engineering, he says, because "it's kind of discovering new things that were unknown before." In this case, the unknown height of well-known Mount Rainier.

"I think people should probably care that the mountains are changing that significantly," says Gilbertson. "Twenty-something feet"—or how much Columbia Crest has shrunk since 1999, leading to its loss of status—"is kind of a big deal."