An Inconvenient Cure

THE PART OF THIS STORY YOU MAY ALREADY KNOW is the stuff of news montages.

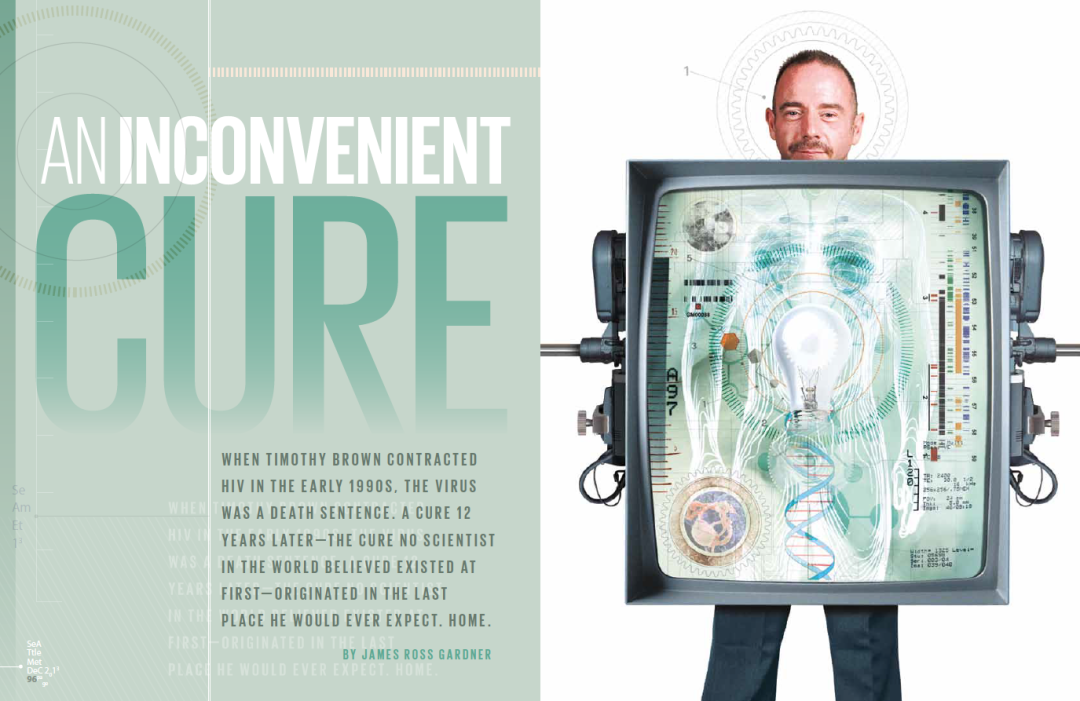

Somewhere between two planes crashing into the world’s financial center and a rover touching down on the red Martian dirt, future audiences gorging on the events that defined the early part of the twenty-first century will get a flash of a skinny man with thinning brown hair, reading glasses on the end of his nose. Either the words will appear on the screen or the man himself will be heard explaining that you are looking at the first person cured of HIV, a plague that spent 30 years killing millions around the globe.

What news archivist of the future could resist Tuesday, July 24, 2012, during the 19th International AIDS Conference in Washington, DC? The day before, then–secretary of state Hillary Clinton addressed the crowd, welcoming more than 20,000 attendees back to the United States, as the conference had not been held in this country since 1990—the year the plague had infected almost 161,000 Americans and claimed the lives of more than 120,000.

There had long been whispers in AIDS research circles and the occasional story in the press about the man cured via an obscure procedure in Germany—a bone marrow stem cell transplant to treat his acute myeloid leukemia that also rid his body of HIV.

That wasn’t the message delivered from the podium. No, Secretary Clinton said that while extraordinary progress had occurred in the past two decades, no cure had been achieved. Later that day, Bill Gates, whose foundation has made AIDS research a top priority, particularly in Africa, made his opinion clear. “If somebody could cure AIDS...that’s very much a long shot,” he told the audience. “It’s probably not in the cards anytime soon, which is why the treatment imperative is so dramatic.” Richard Horton, editor of the medical journal The Lancet, piled on. Global health blog Humanosphere reported that he told attendees, “This kind of language implies we are close to ending the epidemic, and it’s just not true. It’s a marketing strategy, and one that could backfire.”

So it was particularly bold, if somewhat jarring, when Timothy Brown gave a press conference the next day in an out-of-the-way room in DC’s Westin City Center hotel. “Let me be crystal clear: I am HIV negative. I am free of the virus.” Then, as if no one in the audience quite believed him, he added, “Despite what you may have read and heard recently in the media, I am cured of the AIDS virus.”

He followed that with the announcement that he would be dedicating his life and body to the sole purpose of developing a universal cure for AIDS.

How he got there would be a story for another time—a story that begins decades ago and halfway across the planet, if we’re talking the virus. If we’re talking the patient, it begins in the other Washington on—why not?—a bus.

Brown's senior portrait in the Ingraham High School 1984 yearbook

Picture him. Small guy. Curly, brown hair. A public bus brings him from Edmonds, where he and his mother moved shortly after his freshman year, to North Seattle’s Ingraham High School. He sits alone, applying lipstick. It’s the early 1980s and one of Timothy Brown’s favorite musical acts is Culture Club. He wants to be Boy George. The confusion and disdain on the faces of his fellow passengers is obvious. Brown doesn’t care. He’ll never care.

“He was fearless,” recalls one of his best friends at the time, Elaine Fitch, who met Brown when they were 10 years old and their mothers joined the same singles group in a North Seattle church. At school, when someone tried to spread a rumor that he and a friend were gay and having sex together, Brown corrected the record. “He’s not gay,” he said, “but I am.”

Soon only his mother was in the dark about his orientation. Sometimes he went to Northgate mall, the first mall in America, to find other gay teens. It was secret and exciting, even after that time in the men’s room at Nordstrom when store security caught him with a fellow 17-year-old. The store called the police, and Brown sat with the other kid in a back office while the cop tried to reach Mrs. Brown. No answer. The other kid wasn’t so lucky. “Your son’s been arrested,” the cop told the other kid’s mother. “For what?” Brown could overhear the woman say through the receiver.

“For lewd conduct.”

“What was he doing?”

“Fellatio.”

Released from custody, Brown slinked from the store and out onto the curb, where his mother waited as planned. He told her nothing but later wrote a four-page letter explaining to her what had happened. Except he lied. He wrote it was the first time.

“He was very promiscuous,” explains Fitch. “And all of us would caution him to at least be careful. And obviously he wasn’t.”

By 1984, the year Brown graduated from Ingraham, Seattle had already seen dozens of AIDS cases.

ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME FIRST GRIPPED the U.S. when gay men in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco inexplicably contracted and died from pneumocystis pneumonia. AIDS gobbled up T cells until a person’s immune system was nonexistent, leaving him or her vulnerable to a host of diseases. Researchers eventually identified the virus that caused the epidemic, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), and its modes of travel: blood transfusions and sexual intercourse.

The first two Seattle AIDS cases appeared in 1982. By 1987 area physicians had diagnosed about 500 cumulative cases in King County. In 1989 the number jumped to 1,000 cases; 92 percent were attributed to transmission via gay male sex.

That early history is riddled with frustration, beginning with fights over who discovered the virus, who to blame for spreading it, and why no cure or even an effective treatment existed. ACT-UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) kept the conversation kindled, advocating for HIV patients’ rights during a time when U.S. and global leaders turned a blind eye to the syndrome quickly taking the lives of thousands of gay men. Through nonviolent sit-ins and other forms of protest, ACT-UP pressured the Centers for Disease Control, the National Institutes of Health, and the Federal Drug Administration to respond more quickly to the epidemic.

Timothy Brown, now living in Seattle’s Capitol Hill in an apartment on Summit Ave, worked at a bank downtown, took business classes at Seattle University—courtesy of his employer—and, around 1989, joined the Seattle chapter of ACT-UP.

On Thursday, September 13, 1990, Brown and about 40 of his fellow activists disrupted a Nordstrom fashion show at the Sheraton Hotel and Towers downtown. “We’re here!” they chanted. “We’re queer. We’re not going shopping.”

The protestors showered the crowd with pamphlets that censured Nordstrom for its alleged poor treatment of gay employees and employees with HIV. (Among their demands was that the retailer extend benefits to domestic partners.) For another demonstration, ACT-UP filed into the office of then-mayor Charles Royer for a silent sit-in. Except the same guy who squashed a rumor at school by announcing he was gay couldn’t stay quiet for long. Brown broke the silence and loudly articulated ACT-UP’s message—until the others told him to shut up.

In 1990 he toured Europe with Elaine Fitch and another female friend. They explored England, France, Spain, and Greece for three months. Brown’s pursuit of sexual partners, says Fitch, made him a difficult travel companion. “Tim was just going out and meeting people, so there’d be nights where Sherry and I’d be tired, or we’d have to get up and travel someplace else the next day, and he’d go out.” And not return all night. On at least one occasion the women had to catch a train and arrange—via long-distance phone calls with Brown’s mother—to meet him somewhere in the next city on the itinerary. “I was really mad, because, you know, we generally assumed he was okay, but still, you’re in a foreign city, and he just didn’t come back.”

Brown returned to Seattle after three months, but the city had lost its shine. A year later he was living in Barcelona, where he says he “drank a lot of red wine and beer” before finally landing a position as an English teacher at a summer camp for kids. After his Syrian roommate caught him lying naked with a man in the living room and threatened to throw him off the balcony, he moved to Germany, where he worked as a translator.

All the while Brown maintained a robust if sometimes risky sex life: While he usually used condoms, occasionally he didn’t.

Timothy Brown returned to Seattle for a visit in June 2013, six years after his remarkable cure from the AIDS virus.

In 1995, Elaine Fitch, attending law school in San Francisco, answered the telephone. It was Brown, now living in Berlin. He had tested positive for HIV.

“I was furious. Part of it was just the pain and fear,” Fitch recalls. “Just knowing the prevalence of HIV at that point and knowing how promiscuous he was… I remember crying and pounding on the wall. Just being really upset. Because at that point, it was a death sentence.”

An AIDS diagnosis in ’95, when nearly 20 million people worldwide had the virus, was just that. There was no reliable treatment, and the one drug that had proven effective, AZT, was actually killing some patients.

A former partner who also had AIDS told Brown, “You know, we probably only have two years to live.” Facing what he thought was certain demise, Brown decided to focus on his education and continued university studies in Berlin. He waited a year before telling his mother about the diagnosis, though, as she was in her own battle against breast cancer. This time he didn’t leave it to a letter. On a visit to Seattle, he invited her for a walk in a park. He broke the news on a bench. It was her worst fear about her son come true.

Luckily for Brown, a year after his diagnosis a new combination of AIDS treatments, a cocktail of drugs called antiretroviral therapy, was keeping the virus at bay for some patients. The mortality rates slumped off, and the infected were told they might live after all. For Brown, AIDS became an inconvenient—14 pills a day—but manageable chronic illness.

He wouldn’t consider himself lucky for long. In 2006 he started to feel sluggish and constantly tired. Tests revealed he had acute myeloid leukemia. If he was to survive, chemotherapy would have to begin immediately.

During Brown’s second round of chemo at Berlin’s Charité Hospital, his doctor, Gero Hütter, approached him in the hall and said that he’d like to take a blood sample to send to the bone marrow donor bank. The request sur-prised Brown. Chemo, not a bone marrow transplant, had been the decided-upon treatment for his leukemia.

The doctor had an idea.

A receptor known as CCR5 opens the door for HIV to enter the immune system of an infected person. A mutation, delta 32, found almost exclusively in northern Europeans—and only in one percent of that population—shuts off CCR5, effectively closing HIV’s only door into the system. Hütter knew very little about AIDS research, but he postulated that if he could find a stem cell donor for Brown with the delta-32 mutation, he may be able to rid his patient of leukemia and HIV.

A relatively young doctor at 38, Hütter was not prominent at Charité Hospital, let alone among virus researchers. The idea was a long shot, one that no one had ever tried and that no one, not even Hütter’s colleagues, thought possible.

Brown again called his friend Elaine Fitch, now practicing law in Washington, DC, and explained the procedure. “But I don’t like the idea of being a guinea pig.”

“What do you have to lose?” Fitch said. “If this guy’s theory proves true, think what it could do not just for you but tons of other people.”

Brown paused, absorbing the words of one of his oldest friends.

“You’re going to get the treatment anyway,” she added, “so why not try it this guy’s way?”

Hütter’s way wasn’t easy. The doctor identified 232 suitable stem cell donors for Brown and paid $40 per sample to screen for the mutation. Only sample No. 61, from a German male, came up as delta 32.

The procedure Brown would undergo was a standard bone marrow stem cell transplantation developed in Seattle, Brown’s hometown, by Donnall Thomas, the cofounder of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and a Nobel prize-winning researcher.

Brown stopped his antiretroviral regime and underwent the transplant in early 2007. He felt the difference overnight. “More energy and I was able to put on muscle weight. And I was looking better and feeling better,” he recalls. Tests showed zero trace of HIV in his system. Hütter’s wild idea appeared to have worked.

Before anyone could toast the victory, Brown relapsed. The leukemia returned a year after the treatment. “I thought he was going to die at that point,” says Fitch. “I took a trip out to Berlin because I thought I was going to be saying goodbye.”

A second transplant—again with No. 61’s stem cells—was a success. Brown regained his strength, and when he did he was whole and free of both HIV and leukemia.

There was another problem. No one believed it.

Hütter submitted a paper documenting the case to The New England Journal of Medicine, which swiftly rejected it. The claim was too outlandish. Thirty years of AIDS research hadn’t yielded anywhere near what a no-name German physician said he had done.

Fred Hutchinson's Keith Jerome has studied HIV and other viruses since the mid-1990's.

“Scientists are inherently skeptical,” explains Fred Hutchinson’s Keith Jerome, a scientist who has studied HIV and other viruses since the mid-1990s. “We need to show proof. This is incredibly important to people who are affected by HIV, and it was the stuff of science fiction only a few years ago. The last thing you want to do is give people the wrong ideas or raise hope.”

Hütter settled for an explanatory poster at a Boston gathering of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in the winter of 2008. Again, few took the doctor seriously.

Dr. Jeffrey Laurence, an AIDS researcher at Cornell, did. He invited Hütter to speak about the so-called Berlin Patient to a group at MIT six months later. This time a journalist—a science writer at The Wall Street Journal—was present. The resulting article was read around the world.

The New England Journal of Medicine reconsidered Hütter’s claims. It published his original paper in the February 2009 issue, but with a caveat—an editorial in the same issue that threw doubt on the whole premise, penned by one of the original discoverers of the AIDS virus in the 1980s.

“It’s kind of surreal,” says Fitch. “I mean, to think that this scrawny little kid you grew up with is going to change the face of medicine because he was willing to work with this doctor who had this crazy theory. So now he doesn’t have leukemia and he doesn’t have HIV. It’s frankly astonishing.”

Keith Jerome agrees. “When the paper came out in The New England Journal, I said certainly there’s enough evidence here that something really amazing has happened,” he says. “Timothy Brown has been studied very carefully since by a tremendous number of highly qualified laboratories. It’s very clear that we’re not detecting the virus in his body now. So, I’m quite convinced at this point.”

But in addition to doubting Hütter’s claims—even Brown himself says he didn’t believe he was cured until he saw it published in The New England Journal—critics also pointed out the impracticality of the procedure.

Bone marrow transplants are almost prohibitively expensive—as much as $200,000 or more—and notoriously dangerous. Oncologists only recommend it as a last-minute, life-saving resort.

Was there a way to take the concept and adapt it in a way that was practical?

Hans-Peter-Kiem is adapting Brown's HIV cure so that patients won't need bone marrow stem cell donors.

Proof that we are living in the age of miracles can be found at the laboratory of Dr. Hans-Peter Kiem on the campus of Fred Hutch. First a tall woman materializes in the lobby: short angular haircut favored by female leads in films set in the distant future; white sleeveless dress with horizontal blue lines at the hem, which hits just above the knee; a speed walk that leaves you four steps behind through a hallway crowded with lab equipment and into the office of Dr. Kiem.

Kiem sits behind a desk, the verdant campus framed in the window behind him. He favors blue buttonup shirts and a blue pen in the left breast pocket that may or may not be an intentional accent of color.

A German native, Kiem came to Seattle 21 years ago to follow in the steps of his hero, bone-marrow transplantation pioneer Donnall Thomas. Kiem admits that, like his Hutch colleague Keith Jerome, he was skeptical about Brown’s case at first. But he has read the papers, looked at the evidence, and is convinced the Berlin Patient is real. (Two other HIV-positive men in Boston have since undergone a similar marrow transplant treatment and now reportedly show no signs of the virus.)

Until Timothy Brown, Kiem says, cure was practically a verboten word in AIDS research circles. “Before we were talking about vaccines, prevention—which is all very, very important. But really nobody has talked about the cure. He’s launched an entirely new field.”

“Timothy has been wonderful about visiting with the AIDS researchers at our scientific conferences,” adds Jerome. “And he clearly has developed quite a sophisticated scientific mind, and so he’ll often ask questions.”

Kiem’s lab is at work developing a way to take the concept that cured Brown—trading good bone marrow stem cells for bad—but instead of using a donor, patients would receive their own reengineered blood and marrow stem cells; stem cells, Kiem hopes, that will be the equivalent of the delta-32 mutation, shutting the door on HIV so it can’t enter the immune system.

Timothy Brown meets with Fred Hutchinson researchers in June 2013.

In just a few minutes, Timothy Brown will stand in front of more than 150 primary care providers, oncologists, and researchers—an auditorium so packed, dozens of attendees will sit on the floor just to glimpse the one true miracle many of them will ever see in the flesh.

But first, as if he somehow isn’t on the campus of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Brown lights a cigarette. An e-cigarette, mind you, its electric blue tip a pulsar that flares each time he brings the cigarette to his mouth. No smoke—just invisible hits of nicotine to put his bones at ease before he tells the story of how an anonymous expat in Germany became the most famous AIDS patient in history.

It’s June 18, 2013, and Kiem and Jerome have invited Brown and his new organization—the Timothy Ray Brown Foundation, the first organization solely dedicated to finding an AIDS cure—to the Hutch for a two-day symposium that will include a cocktail hour with the scientists and multiple talks by the researchers and Brown himself.

In the courtyard on campus, Brown takes a seat at an ornate metal picnic table in the shade of a maple tree. When he sits his charcoal blazer collapses outward in pillowy folds, so that, even at 47, he looks like a boy in a grown man’s suit. He takes another drag on his e-cigarette. Until 2010 he was known in the medical literature simply as “the Berlin Patient”; a German newspaper profile identified him as “Neil.” He came forward at last, he says, because he didn’t want to be the only person cured of AIDS. He was, in effect, tired of being a walking miracle who could not help others. Since then he has rubbed shoulders with the likes of Nancy Pelosi and Sharon Stone and spoken to crowds all over the country. (He now lives in a suburb of Las Vegas.)

Inside his body flows the secret that has escaped researchers since the virus was first discovered—the way to shut the door into the immune system, keeping out one of the worst plagues of our lifetime. Brown knows we have so far to go: Some 1.7 million people died worldwide from AIDS or AIDS-related complications in 2011.

He rises from the picnic table. His blazer falls flat against his lanky frame and he cuts across the courtyard. A pair of glass doors open then shut behind him. And Timothy Brown steps in front of the crowd to speak.

This article originally appeared in the December 2013 issue of Seattle Met.