Fire at the Sanctuary of the Apes

For the third time in 25 minutes Chief DJ Evans commanded his firefighters to fall back. It was either fall back or burn to death. The grass, scrub brush, and trees on the slope between the river and the firefighters on the highway were engulfed in flames—flames that an erratic 30-mile-per-hour wind threw in all directions. The men felt the heat from the blaze on their faces, the blast of air from the fire’s convection winds against their chests. And now, what moments earlier seemed unthinkable: The conflagration shot flames over the tops of the fire engines and onto the other side of the road.

And so Chief Evans, five volunteers, and his wife, Captain Kay Evans, retreated another several yards down the highway. But within seconds they were back in the same situation. The flames kept lunging at them.

The chief took stock of the inferno once more. He’d never seen anything like it in his 18 years of combating wildfires. The hillside erupted as if soaked in gasoline. He had called for backup and by now every fire district in the county, from Cle Elum to Ellensburg, knew about the big burn on Highway 10 at Taylor Bridge. They’d all engage it soon, along with firefighters from all over the state—a 1,000-person force locked in battle with a flame-throwing monster that would last for more than two weeks. But at the moment it was just Evans and his small band of volunteers.

The fire now flanked them on both sides of the highway. The water they sprayed evaporated on impact. Finally, at about 2pm, Monday, August 13, 2012, some 45 brutal minutes after arriving on the scene, Evans made the order. A full evac, which meant that the men—and one woman—of the Kittitas County Fire District No. 1, headquartered in the town of Thorp, population 240, were taking their two fire engines and getting the hell out.

Fire on the Mountain The Taylor Bridge Fire erupted on the afternoon of August 13, 2012, and quickly jumped over ridgelines and into neighborhoods miles away, eventually consuming 36 square miles and destroying 61 homes.

Image: Steve Bisig

J. B. Mulcahy’s eyes opened at 6am. He was wide awake. Years of rising and working before dawn had wired his mind to fly across the border between slumber and consciousness. So although it was his day off, staying in bed to catch more sleep wasn’t an option. Diana, his wife of two years, partner for 12, lay next to him, plunged in a world of dreams she wouldn’t swim up from for another three hours.

Mulcahy padded to the kitchen to make breakfast. Purple sunlight glowed through the window above the sink. Blond, bearded, and blue eyed, Mulcahy, 35, resembled actor Ryan Gosling, if Ryan Gosling wore the tan, weathered look of a man who spent his days on an old farm, as Mulcahy did, driving a tractor, mending fences, collecting pieces of scrap metal.

If Mulcahy could be described as a farmer, then he was by far the strangest kind of farmer in the Northwest. He didn’t raise horses, like his nearest neighbor, or cattle, or any other type of livestock or crops. In the mustard, two-story building 120 yards from where he stood resided seven chimpanzees. Four years earlier, having endured a lifetime of clinical experimentation, the primates caught a break after a Seattle man spent part of his severance check from a bio-engineering firm on a 26-acre farm six miles outside Cle Elum—80 miles east of Seattle—and converted it into Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest. He and a board of directors hired Mulcahy, along with Mulcahy’s then-girlfriend Diana Goodrich, to help run the sanctuary.

Cle Elum, population 1,900, had embraced the chimps, showering the facility with donated fruits and vegetables, cash, toys, and blankets. In 2009, the city council voted unanimously to proclaim the Cle Elum Seven—Annie, Burrito, Foxie, Jamie, Jody, Missy, and Negra—honorary citizens of the town.

Mulcahy and Goodrich now lived in the one-story brown clapboard house adjacent to the chimp building and led a team of caretakers and volunteers, two of whom were taking over that Monday’s feedings so Mulcahy and Goodrich could enjoy a day off.

As the light through the kitchen window brightened and the house warmed, Mulcahy grew restless. The plan was to go on a hike, something the couple hadn’t done for a long time. But Diana, to his ongoing frustration, was a late riser. So he paced until she woke—and paced some more as she did laundry and dressed and ate her usual breakfast: a plate of blueberries. Finally, a little before 1pm, they filed out of the house and into their silver VW Rabbit and wheeled down the gravel path onto Highway 10, westbound toward the Pete Lake trailhead.

Taylor Bridge, less than a mile up the highway from the sanctuary, had been under construction all summer. Stretched over a dry gulch that lay 250 feet north of the Yakima River, the bridge was undergoing rebar replacement. Locals had grown used to the detour that sent them up a dirt road and around the construction site. But as J. B. and Diana approached they saw something that caused J. B. to hit the brakes.

Flames danced around the bridge.

J. B. Mulcahy with Missy

The couple hopped out of the car for a closer look. The vegetation between the bridge and the river was on fire. A construction worker shoveled dirt onto part of the blaze, while another hard hat tossed equipment into the back of a pickup. A few yards east a tree lit like a torch. On the bridge: more workers, some frantically calling down to the hard hats below, while others threw construction tools and, soon after, themselves into trucks.

J. B. and Diana didn’t know it at the time but they were witnessing the early moments of what would grow into one of the largest, most destructive wildland fires in the history of Kittitas County. What they did know was that the men had lost control of the conflagration and were fleeing.

They jumped into the VW and raced back down Highway 10 a quarter of a mile and pulled off to the side of the road. J. B. phoned the sanctuary. “Get the chimps inside. We’ve got a problem.”

He hung up and looked back at the fire. The flames had already reached the spot where the couple had been parked just minutes earlier.

Kittitas County Fire District No. 1, formed in 1943 after a series of forest fires nearly turned Thorp, 18 miles east of Cle Elum, to ash, is the oldest fire district in the state. Demand for emergency assistance in the 43.5 rural square miles that the 18 volunteers of District 1 protect had exploded in recent years. They responded to 180 calls in 2009, compared to just 25 in 2000. Yet until four years ago, when fire chief DJ Evans and his team received a $165,150 grant from Homeland Security for protective apparel, radios, pagers, and other gear, most of the volunteers had been using hand-me-downs or outdated equipment.

On the morning of August 13, Chief Evans, 60, and his wife Captain Kay, 56, had rallied a handful of volunteers to offer potential backup to another district, District 7, which was extinguishing a series of small burns near Cle Elum. But the crew had known for days the Big One was coming. Conditions were ripe: The region had experienced a long, wet spring, so grass grew extra tall and thick. In July the rain stopped, the temperatures hovered in the 80s and 90s for weeks, and the wind was relentless. “Really, we were just waiting for the hammer to drop,” the chief would later explain.

The drop came in the form of a brush fire next to a construction site at Taylor Bridge, possibly caused by a welding mishap. By the time District 1 arrived, at 1:21pm, some 20 minutes after the first spark—and less than 10 minutes after J. B. Mulcahy and Diana Goodrich raced back toward the chimp sanctuary—the blaze was exhibiting what Evans calls “extreme behavior”; so extreme the crew retreated three times before ultimately seeking refuge at a makeshift command point.

Flames lurched at the sanctuary all day and night

Image: Steve Bisig

From the command point, an open, relatively treeless (and therefore easily defendable) space about a mile from the fire, Evans was better able to strategize. He turned to his wife and asked her to head west, back up Highway 10 in the direction of the fire to scope the situation at the chimpanzee sanctuary. Captain Kay had heard of the seven apes—everyone had—but because the facility was closed to the public, she’d never seen the primates and didn’t know what to expect when she drove up the gravel path.

She beheld a blur of activity. J. B. Mulcahy ran around the property, setting up sprinklers to wet the grass. Diana had packed their dog and two cats into the VW, which sat idling under a tree with the air conditioning blasting. The two caregivers on duty, Elizabeth Kuykendall and Jackie Buckner, were hosing down the grass around the chimp building.

Captain Kay surveyed the property through the eyes of a firefighter, mentally measuring the space between structures, determining which were the most and the least defensible. The farm sat on a slight incline. At the top of the hill, on the east side and surrounded by a 14-foot-high electric fence, was the two-acre field that constituted the chimps’ outdoor play area, filled with tire swings and climbing structures. Below the field, and also surrounded by an electric fence, was the steel and concrete chimp building, with an attached open-air cage on its east end and a kitchen, mostly made of wood, on its west end. Northeast of the chimp building sat an old wooden barn, and further north, J. B. and Diana’s clapboard house.

Captain Kay confirmed the couple’s fear. The fire was coming right at them. J. B. explained that moving the chimps would take hours, days even. They’d have to be anesthetized and placed, one at a time, in a single-chimp crate, and carefully trucked off the property. The Cle Elum Seven would have to stay. Moreover, J. B. was staying with them.

Kay looked around. Allowing residents to remain on the property during a fire was against protocol. But no one on her crew knew the first thing about chimpanzees. If something went wrong, they would need the primatologist’s expertise. “Okay,” she said. “But everyone else should get out.”

Diana and the caretakers didn’t want to leave, but they also didn’t want to make the firefighters’ job any harder. J. B. said goodbye to his wife, watched her and Elizabeth and Jackie disappear down the gravel road in their cars, powered down the electric fence lest the firefighters get shocked, and began walking into the chimp building. Kay stopped him.

“One more thing,” she said, “If it comes down to it, would you prefer we save your house or the chimp building?”

Diana sped east along Highway 10. In the VW Rabbit’s backseat sat her dog Honey B, a chow, and further back, in carriers, two cats, Lulu and Peanut. She found a spot in the road far enough from the fire to stay safe but close enough that she could see what was happening to the sanctuary, and pulled over.

A giant plume of smoke, maybe 500 feet tall, advanced toward the chimps, her house, and her husband. At the bottom of the plume, a gash of flames cooked through the vegetation surrounding the property and threatened to cook through all that she loved.

Her world was populated by knuckle-dragging apes, prone to throw toy furniture and scream like patients in an asylum, but it was also marked by a strict schedule; breakfast for the chimps at 9:30am, lunch at 1pm, dinner at 4:30. And it was a world more than a decade in the making. She met J. B. while at Central Washington University in Ellensburg in the late 1990s. Both studied under the legendary primatologist Roger Fouts, renowned for teaching sign language to Washoe the chimp. After graduation, she and J. B. worked at the Fauna Foundation, a chimp sanctuary in Montreal, and she followed him when he took a post at a sanctuary in upstate New York.

But this, this was a sanctuary they helped create. Their former classmate Sarah Baeckler was the executive director; J. B. was the director of operations; and Diana helmed communications and development. And it was home. In 2010, she and J. B. were married on the property, yards from the back door of their house.

Now only the sound of her husband’s voice crackling over a two-way radio tethered her to that world. His words, broken over the airwaves, narrated for her the activity he witnessed through a window in the chimp house. After a helicopter hoisting a water bucket arced over the farm, he explained, “Where the helicopter dropped the bucket, it’s still burning in that little gulch.”

Then Diana, from her unique vantage point on the highway: “All of the trees just above Young’s Hill”—referring to the chimps’ two-acre outdoor area—“look like they’re going up now.”

J. B.: “Oh, that’s going to be nasty.”

The fire had enveloped the entire ridge above the farm, circled around the property clockwise, and was now incinerating the grass and trees on both sides. Smoke blanketed the hillside, and Diana could barely make out the sanctuary from the highway. Panic rose in her when, for half a minute, J. B. failed to answer her questions. Then the most startling thing yet squawked through her radio speaker: “The house is on fire.”

A helicopter dropped at least five buckets of water on the chimp sanctuary

Through a rectangular window in the chimp building he watched figures in bright yellow suits stride in what looked like slow motion across the sanctuary. The scene that scrolled by wasn’t the rapid action of firefighting that movie screens had taught his brain to expect but the methodical motions of men and women, clad in fire-resistant Nomex shirts and pants, strategizing against an inexorable threat.

And it was dead silent. The building, its windows and doors shut to keep out the smoke, blocked all outside noise. Even the helicopter that hovered every few minutes was muffled. More eerie, though, was the absence of sound inside the 18,000-cubic-foot structure. In the four years J. B. had worked at the sanctuary, the chimp house had hardly been so hushed. The ringleader, Jamie, usually had her fellow apes spun up into some primitive drama, a howling tizzy, say, that kept them distracted long enough for her to steal their nectarines. Or Burrito, the only male in the tribe, would gun baritone hoots at no one in particular. Or the whole lot would crash into the playroom after lunch and rip cardboard boxes to shreds or climb the cage walls or swing from the monkey bars.

But instead the Cle Elum Seven sat completely still, as if hoping to go un-noticed. The only other time J. B. had seen the chimps so listless was when he first met them.

In 2008 they were property of the Buckshire Corporation, which rented animals to laboratories for scientific research. In its facility 40 miles outside of Philadelphia, Buckshire trafficked in primates, dogs, cats, and rabbits. In 1994 a former employee claimed she witnessed another worker kill 20 kittens he deemed superfluous—by snapping their necks with his bare hands. That same year Buckshire was the subject of a U.S. Department of Agriculture investigation and charged with 16 animal welfare violations. Most heinous was the dank basement where dozens of chimpanzees languished in 18-square-foot cages, much smaller than the minimum size required by law. The chimps only left the tiny metal jails when carted off to the lab for liver biopsies that determined the degree to which experimental hepatitis vaccines had destroyed their organs.

Bending to pressure from the feds and groups like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Buckshire spent the next decade and a half unloading its chimp population, releasing the animals to sanctuaries around the country. But there were still seven left: Annie, Burrito, Foxie, Jamie, Jody, Missy, and Negra.

In June of ’08, J. B. and Keith LaChapelle, the man who created the Cle Elum sanctuary, flew to Pennsylvania to meet the apes and escort them to Washington state. They watched the Buckshire technicians roll the limp, anesthetized chimps out of the facility and into a trailer, then they followed the truck and trailer across the continent. They rolled nonstop, one man sleeping in the cramped passenger seat of a Dodge Neon while the other drove, only pausing at truck stops to feed vegetables to the stunned, silent chimps in the trailer.

They arrived at the sanctuary on June 13. The chimps were pale; they hadn’t seen sunlight in years. And they didn’t make a sound for days. “Chimps in the wild,” J. B. would later explain, “make a lot of noise, even when they’re scared—unless they’re scared of something they don’t understand. Then they’ll just hang back and observe before they react.”

Which is what they seemed to be doing now, as the fire burned outside their door. Jamie and Burrito sat stationed at windows, studying the firefighters’ measured movements. J. B. found Foxie sitting away from the glass, leaning against the wire mesh of the playroom cage. He pressed the top of his hand against the mesh. The chimp filled her nostrils with his scent and kissed his hand. “You okay, Foxie?” he whispered.

He had told Captain Kay that if it came down to a choice, of course he preferred the firefighters save the chimp building rather than the house. Now came the reckoning for that decision. During the hour or so he had observed the fire, he developed a system for determining what was burning. Trees, grass, and brush set off light to dark gray smoke. But every once in a while he’d spot black smoke and know that something man-made had caught fire, like a fence or piece of farm equipment. And now he saw black smoke right where the house was. He radioed Diana to tell her their home was gone.

But he had more on his mind. The sanctuary staff had agreed long ago that, no matter what happened, under no circumstances would they ever release the chimps from the confines of the building and outside enclosure, not even so they could escape a fire. The danger was too great to any humans caught in the chimps’ path. The staff members themselves were never in the same space at the same time as the unpredictable and volatile animals, which are three to five times stronger than any man and have been known to rip off human fingers and toes and gnaw faces clean off of skulls.

The building, all steel and concrete, couldn’t burn, but if anything right next to it caught fire, such as the attached, mostly wood kitchen, the structure would likely fill with smoke. The best thing J. B. could do for the chimps in that case would be to release them into the small open-air cage connected to the building and hope they could stay low enough to the ground to breathe oxygen.

He had a lot of time to mull such a scenario. Diana had left Highway 10 to take the dog and cats to a friend’s house in nearby Roslyn and was out of radio range. Elizabeth and Jackie, the volunteer caregivers, had also been on the highway with radios, but they were now out of range, too.

He paced back and forth in front of the mute chimps, much as he had that morning while waiting for his wife to wake up. Finally, around 4:30—three and a half hours after he and Diana first spied the flames at Taylor Bridge—he stepped out of the building.

J. B. wandered through a yellow miasma of smoke and made out, to his surprise, the faint shape of his house. It hadn’t been incinerated. (He would later learn that the black smoke he witnessed was from a pile of pallets behind the house.) As he inched closer to the home he came across a firefighter lying facedown. The man held a cellphone to his ear and he was sobbing. J. B. asked if he was okay. The man explained that he had just learned that the fire had reached his own house and burned it to the ground.

Captain Kay Evans fought to keep from being swept up in the events unfolding over the radio. In a little less than two hours, the Taylor Bridge Fire, for which she, her husband, and five volunteers had been the first responders, had spread over ridges and into neighborhoods miles away. She could hear the raw details in the grainy radio voices of firefighters. Homes were being evacuated, and homes were being swallowed whole by flames. Occasionally she heard her husband, Chief Evans, pitched in some fiery maelstrom, or the voices of her friends, caught between downed power lines.

But she trained her attention on the ground burning all around her. The battle at the chimp sanctuary—where she led four, sometimes five of her fellow District 1 volunteers—was going to be a long one. She had been a firefighter since 1997, and, like her husband, she’d never seen a blaze behave like this. They had sprayed down a heavy perimeter of water around the property, but a wall of flames, fed by a brisk wind, kept creeping closer, burning through half of the chimps’ outside enclosure. Every so often a tree exploded like a roman candle.

She could see that J. B. and the sanctuary staff, either intentionally or by accident, had created an effective, defensible space around the chimp building. There were no overhanging trees and a rutted tractor path encircled the structure.

The house, though, was in danger. A helicopter dumped bucket after bucket on the home. And a District 1 firefighter sprayed gallons of water onto the roof while another man, a firefighter from District 2, climbed on top of the house and axed away burning shingles.

Radio reports of homes throughout the region going up in flames became more frequent. And around 4pm, Captain Kay watched one of her firefighters fall apart in front of her. A neighbor had called to tell him his house was gone.

Caring for her firefighters was half the job. As the afternoon wore on, she remembered that one of her volunteers was diabetic, and so she approached J. B., now outside of the chimp building, and asked if he could make the man a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

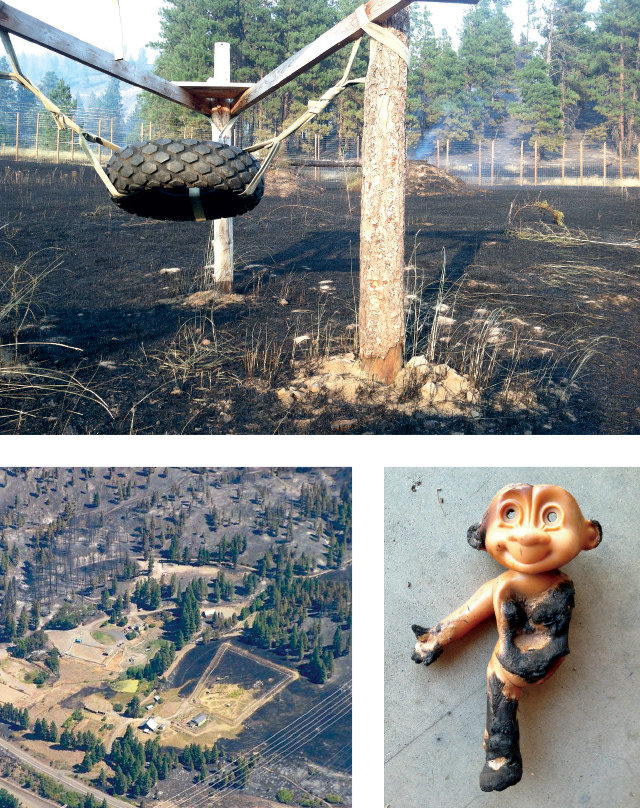

Something Salvaged, Everything Burned Clockwise from top: The chimps’ outdoor enclosure after the fire; one of Foxie the chimp’s beloved troll dolls; an aerial view of the space Kittitas County Fire District No. 1 defended throughout the night of August 13, 2012.

In the early evening Diana Goodrich returned to the sanctuary, as did Elizabeth and Jackie, briefly, to bring bottled water for the chimps. Captain Kay didn’t object. But as the sun went down she and her team were still at it.

All night they fought back the blaze as it threatened to overtake the sanctuary. She and the other firefighters took turns catching quick catnaps in the fire engine, and stayed on long after sunrise, when the full light of the morning revealed all: a charred, denuded hillside and the nearly untouched sanctuary in a sea of black.

Diana and J. B., who had slept in the chimp building’s kitchen—and awoke to a suddenly noisy primate troupe demanding its morning fruit smoothies—brought Kay and the men coffee. J. B. felt a slap on his back and turned to see the firefighter who’d been in tears the day before, a smile now splitting his broad face. The man had just come back from his home, which had not burned after all. Like J. B. and Diana’s house it had been covered in smoke, causing his neighbor to think it was in flames.

As they chatted about the events of the day and night before, Kay noticed J. B.’s Run for the Apes sweatshirt, advertising a recent fundraising 5k. Kay didn’t say anything, but she thought that maybe she would like to run in the race next time; that now that she felt part of the sanctuary, she would like to be involved with it.

Then, around 10am, she steered the fire engine down the gravel path and onto the highway. The rig’s windows framed a radically changed world. Homes and farms were piles of darkened rubble. Entire swaths of trees were black, skeletal versions of their former selves.

And the Taylor Bridge Fire had only been burning for less than 24 hours. It would eventually consume 36 square miles (an area roughly half the size of Seattle), destroy 61 homes, and take a thousand firefighters 15 days—and $10.1 million—to fully contain it. By early October the cause of the fire was still officially undeclared. But the Washington State Department of Transportation had informed Conway Construction, the contractors working on the bridge that day, that it would likely be liable for the estimated $8.3 million in damages.

Even that was just the beginning of the region’s problems. Days after the Taylor Bridge Fire blinked out, lightning struck the parched Cascades and set some 90 new blazes, choking the towns of Winthrop and Wenatchee with smoke to the point of mandatory evacuations.

But for now Captain Kay steered down Highway 10 and then onto Interstate 90 toward home, tired and sore and knowing that she had just helped save the home of seven chimps and two humans.

Four days later, Saturday, August 18, the town of Cle Elum hummed with activity. Engines, bearing the insignias of fire districts from all over the state, Seattle to Spokane, rolled up and down First Street, ferrying water, supplies, and men and women between the inferno and Cle Elum-Roslyn High School, the staging area for the firefighting. In the school lobby a dozen rectangular tables constituted a command center. A map on the wall, updated hourly, tracked the Taylor Bridge Fire’s progress. Firefighters caught quick naps on cots in the darkened gymnasium. Behind the school was a sea of tents, where more fighters slept.

The hillside around Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest looked like Mordor—a coal-colored surface from which heat rose in curly shafts of smoke. The mercury hit an oppressive 93 degrees. And the chimps had yet to venture out onto the half-burned Young’s Hill.

Around 2pm a fire engine grumbled up the path. Three firefighters, volunteers from Snohomish County Fire District No. 26, piled out. They were there, officially, to inspect the property for hot spots, fires that lurk underground and inside burnt tree trunks and can ignite at any moment. But really, they just wanted to see the chimps.

At the sight of the truck, J. B. Mulcahy and some friends took a break from minor repairs. Diana Goodrich and three other caretakers lured the primates out of the building and into the open-air cage with carrots and bottles of water. The firefighters agreed to sit for a photo in front of the chimps, which had lined up, chomping on carrots.

Diana raised her camera and counted before snapping the shot. “Okay, guys, one, two…” Just then Jamie, the mischievous ringleader, climbed to the top of the cage and spit a mouthful of water down on the firefighters, who squinted, smiled, and wiped the water away.