The True Tale of Seattle's Sherlock Holmes

The telegram went out at 4:55am, from a small town in Southern Oregon. “NEED SERVICES OF DETECTIVE TO SOLVE MURDER CASE,” it read. “RELATIVES SUSPICIONED.”

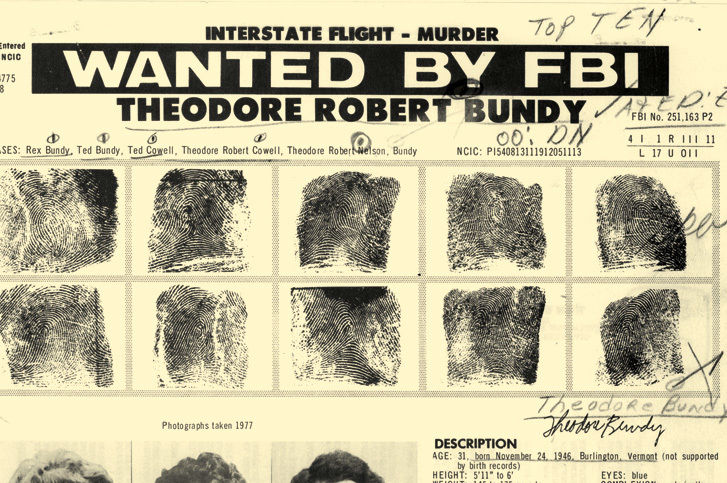

It traveled hundreds of miles up the West Coast to the stately Arctic Building on the corner of Third and Cherry in downtown Seattle. Outside on the facade were terra-cotta walrus heads carved like Gothic gargoyles. Inside was the desk of Luke May, president of Revelare International Secret Service.

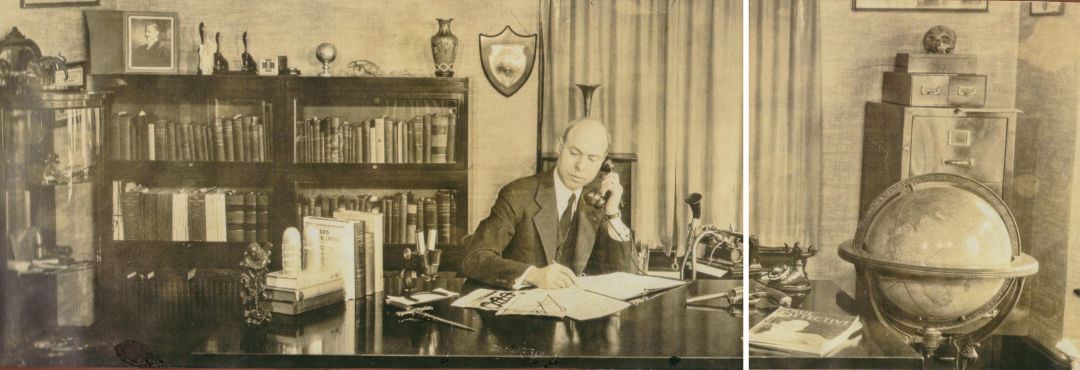

May, only 30 years old, was the founder and lead investigator of Revelare. Humphrey Bogart as famous sleuth Philip Marlowe would have put his feet up on the desk; Nick Charles of The Thin Man would have poured a bootleg dry martini. But Luke May, real-life private detective whose big, glossy desk was ringed by bookshelves and knickknacks, simply added it to his roster of open cases.

It was September 6, 1923, three days after Ebba Covell had been murdered in Oregon. Homemaker Ebba was wife to chiropractor Dr. Fred Covell, mother to three young children, stepmother to two teenagers, and caretaker to her husband’s disabled brother, Arthur. They all lived together in a square, shingle-sided house a few miles outside Bandon by the Sea on the Oregon coast, with a front porch no bigger than a closet.

On Monday—Labor Day—Ebba’s stepdaughter Lucille had taken the three little ones outside, where Uncle Arthur reclined in the early September sun. Sometime before midday, 15-year-old Alton found his stepmother on the kitchen floor, unresponsive. Arthur phoned his brother in alarm sometime around noon.

Now, Ebba Covell had always been known to panic. She’d call Fred when she thought a child had caught diphtheria (it was a cold) or nearly died from a tumble (they were fine). “Excitable,” the neighbors called her. So it wasn’t exactly a surprise that when Fred Covell took off from Bandon to address the emergency at home, he didn’t drive any faster than usual.

This time an emergency had truly erupted. Ebba was unresponsive, and the right side of her face was a strange orange-red color. By his own claim, the chiropractor’s attempt to resuscitate his wife lasted a half hour before he contacted Ebba’s father, a lighthouse keeper in Umpqua, and then the undertaker. No one ever ran for the nearest neighbors, a quarter a mile away.

Police had to travel a dirt road down to the Covell homestead. Today this stretch of Oregon is dotted with golf links—the famed Bandon Dunes course on the rugged coast, the public Bandon Crossings inland—and RV parks, but in 1923 the passage was treed and empty, tire ruts dug into the ground like cat scratch marks.

Officers grilled Fred Covell on his wife’s injuries—which he couldn’t explain. Why did it look like her body had been moved and her clothing had been changed? They asked Fred about his past wives, too—all three of them. One he’d divorced, he said. The others died of cancer and in childbirth. The police noted, and the newspapers would repeat, that Fred couldn’t recall the maiden names of all the past Mrs. Covells.

A local coroner’s jury determined that Ebba’s floppy neck, in sharp contrast to her stiff body in rigor mortis, had been lethally broken, and that bruises suggested a fight. Even in an era without Dateline episodes to binge, police could cast an easy eye to the doctor husband with no answers: one who happened to manipulate necks for a living. Fred Covell was arrested, and the murder of Ebba Covell was solved.

Until Luke May showed up.

Image: Courtesy MOHAI

He’s been called the American Sherlock Holmes, but Luke May was more a Jazz Age blend of Encyclopedia Brown and CSI, more eager nerd than debonair celebrity. By the time he hopped on a train south to the Oregon coast in 1923, he’d already been a private investigator nearly half his life.

He solved his first case—a murder—at 17 years old by befriending police in Salt Lake City and finagling an invitation to a crime scene. There, he noticed an out-of-place handsaw that had escaped everyone else’s attention. Tracing its origins led to a suspect, an arrest, a conviction for murder, and ultimately an execution. From the beginning, Luke May was a closer.

But May was not a cop. In the early twentieth century, city police departments employed their own detectives, but few were trained with any sophistication. They might not even write anything down while investigating. When a crime proved too complex or too mysterious, or there was physical evidence to analyze, departments hired outside consultants like May. The concept was familiar in 1923, given that Arthur Conan Doyle was still churning out new tales of the fictional “consulting detective” Sherlock Holmes.

May was not a detective to rhapsodize on the criminal mind. He constructed his cases like Lego sets, bit by solid bit until the structure was completed and ready to stand up in court. Over the course of May’s career, his firm solved hundreds of crimes this way, an average of one to two new ones every week.

Image: Courtesy Mindi Reid

Call it a Midwestern work ethic. Born in Nebraska in 1892, May’s family moved around as his father farmed and did carpentry, eventually settling in Salt Lake City. May never graduated from high school or attended college (not that most police department detectives went to college then either), but he studied criminology ravenously, even though few books existed on the subject and even fewer were in English.

The teenage May would sit in the galleries of Utah courtrooms watching trials to understand how a criminal case was made. He absorbed knowledge as a habit; when he had to go undercover at a business school later in his career, the detective used the opportunity to learn some bookkeeping.

Despite his upbringing, no one would mistake the dapper May for a farm boy. His personal uniform was a three-piece suit, and when his hairline crept to the polar regions of his head at a young age, he picked up a kind of proto–Stanley Tucci vibe. Though known for his wide-brimmed fedoras, he was most often photographed with his scientific equipment, jacket removed for lab work.

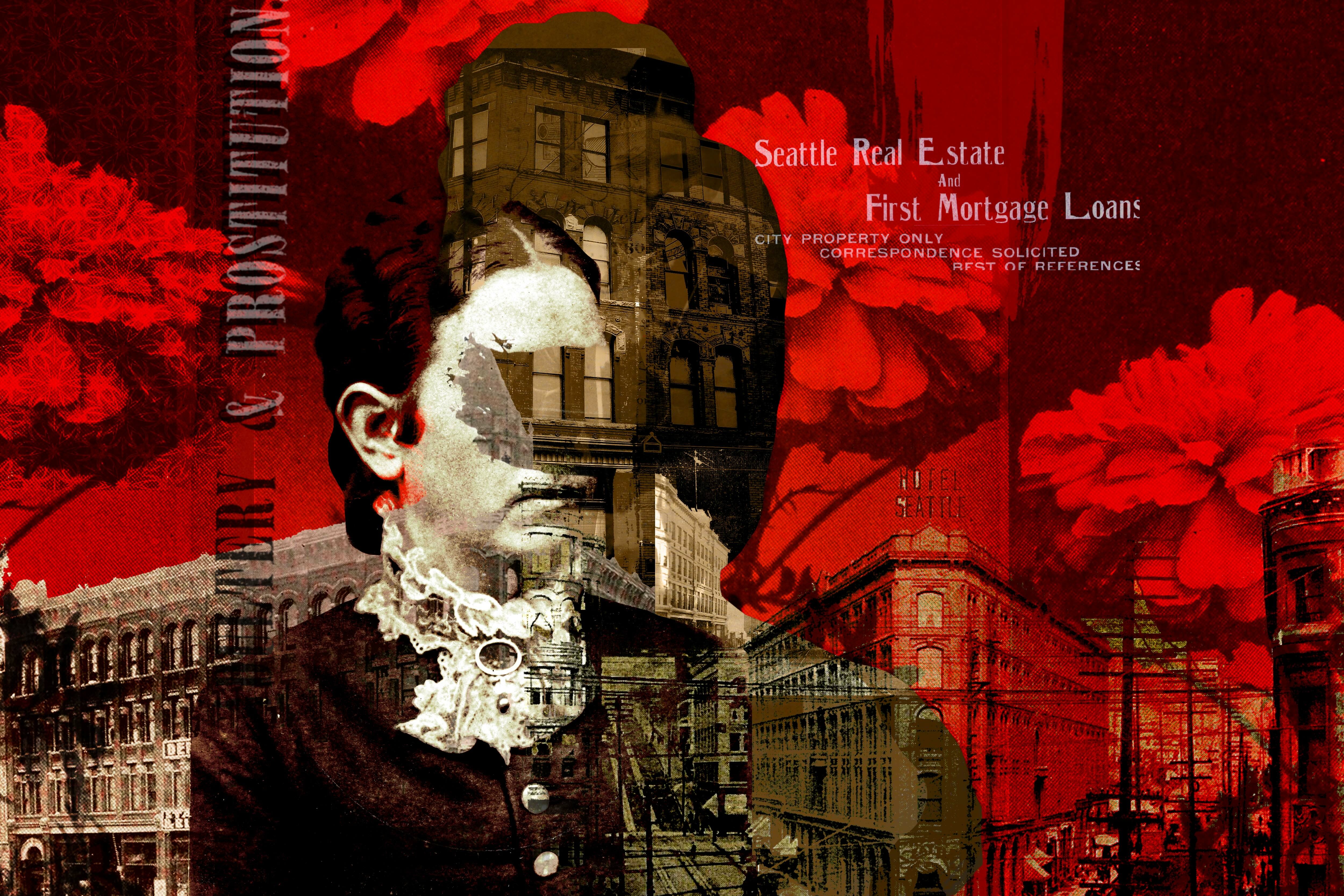

May launched the Revelare agency in Utah in 1914 before quickly moving to Pocatello, Idaho. There he solved cases with one foot still in the Wild West—cases populated with seedy brothel denizens, dance hall girls, and dead gamblers. At some point in his life, May began to lie about his age, shifting his birthday six years back to 1886. For a man who quested after the truth in his work, May was not above a little fakery to project more experience.

In 1919, May moved his agency one last time, to Seattle. The city was still buoyed by the turn-of-the-century gold rush up in the Yukon, and still growing fast. There were many more people than in Idaho, and so many more crimes. Prohibition had just been ratified, and Seattle’s proximity to Canada suggested fertile ground for illegal businesses. That era of the city could be summed up by the fact that when a Seattle Police Department lieutenant launched a booze-running business while still on the force, he was so popular that he was nicknamed “the Good Bootlegger.”

If May arrived in the state as a wunderkind, his work here made him an institution. He found fame in his ability to solve cases with provable science. He and his small staff were hired by Seattle police but also departments in Chehalis, Tacoma, and Aberdeen, and in small towns like Roy and Sultan. The Great Northern Lumber Company hired May to figure out who put a bomb in their dam in Leavenworth.

In the charged, conspiratorial aftermath of the Centralia Tragedy of 1919, in which American Legion members attacked an Industrial Workers of the World union hall and were met with deadly gunfire, May was brought in by the prosecution to conduct forensic analysis on the weapons. But May was not an ideologue: He cared more about hard facts than politics and was as eager to exonerate as he was to convict, if that’s where the evidence led.

May drove his roots deep into the Seattle soil. In the 1920s, he hired a stenographer named Helen Klog. Raised in the Yukon Territory during the gold rush, her parents had sent her south as a teenager for greater opportunities. May, already twice divorced, wooed his employee and proposed to her in a cemetery while out working a murder case.

Image: Seattle Met Composite and Courtesy Mindi Reid

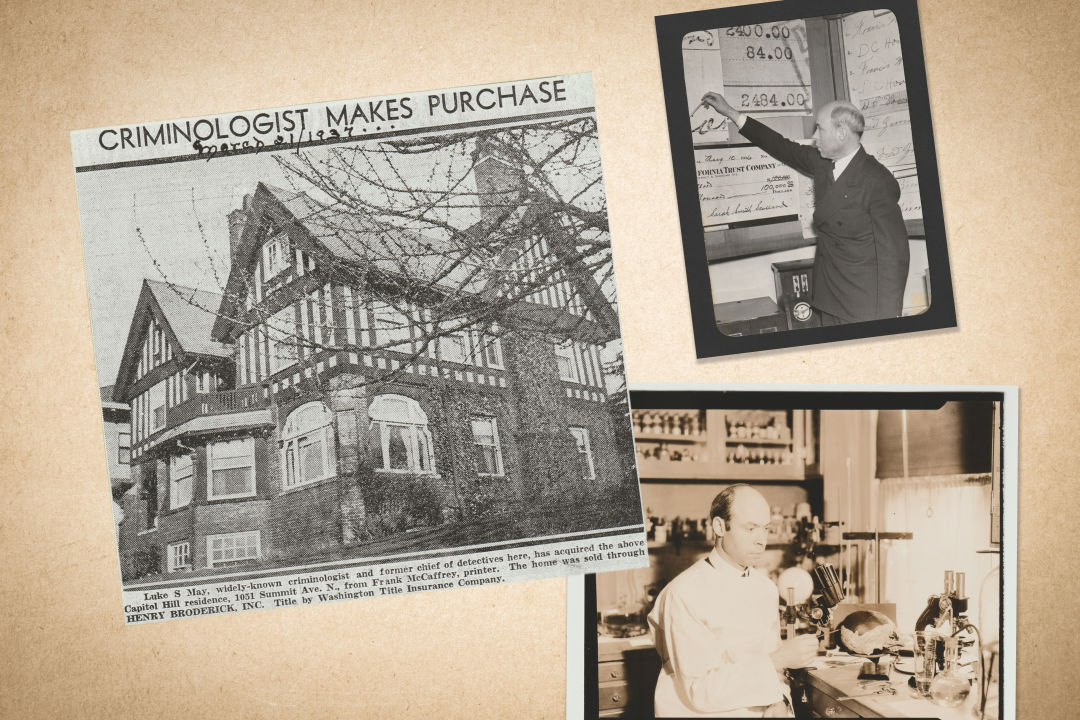

May’s reputation—and bank account—grew. In 1937, after he and Helen had daughter Patricia, he bought a mansion on Capitol Hill, just west of the famed Millionaire’s Row. The Tudor Revival facade aped traditional English architecture. Like Seattle, which wasn’t yet a century old, Luke May had speedrun from establishment to high society in record time.

There were stained glass orioles in the windows and a sweeping view of Lake Union. The Mays hosted grand parties, and, though used to an upbringing where a dogsled was still a practical means of transport, Helen played the elegant hostess while the detective mixed his famous margaritas. He’d dip the rim of one glass into sugar for young Patricia before she was sent to bed.

May no longer commuted from apartment to office building, running his agency out of his home, complete with a laboratory and firearm test space. For Helen, the house was a burden: At more than 4,000 cavernous square feet, and demanding a domestic staff just to keep up, she called it “a woman killer.”

For all his spirit when it came to scientific crime-solving, May was a relatively taciturn man. In his writings, he comes across as disdainful of lesser professionals. In one chapter of his own book, he derides the “almost ludicrous” causes of death listed by a coroner who dashed off worthless conclusions like “Could be assault or diabetes” and “Died suddenly.” May likened the man’s work to a child’s guessing game.

May was process-oriented. A logician. His entire career was devoted to the kind of work relegated to the montages in crime shows—every step following the one before, thorough and exhaustive. But it worked. And May typically followed his cases to the very end, usually into the courtroom to testify.

Revelare logged 127 cases in 1922 alone. His most famous cases came to have nicknames that could have been titles written by Conan Doyle or Edgar Allan Poe: The Bremerton Massacre. The Mahoney Trunk Murder. And, in Bandon, the Murder by the Stars.

Luke May would call the murder of Ebba Covell one of the weirdest mysteries of his career. The case would eventually involve diabolical plotting, underage proxies, secret codes, murder by proxy, and a thwarted crime spree—but at first, it was about mistakes.

May had been summoned to Bandon by Benjamin Fisher, a sharp Coos County district attorney who nevertheless always seemed to wear jackets too small for his shoulders; when newspapers called him “youthful,” they may have noticed he looked like a schoolboy who’d outgrown last year’s uniforms. May’s rate was a $1,000 fee—that would be nearly $19,000 in 2025—plus $6 per day and expenses; he billed his initial trip south on September 8.

The first thing he found were Ebba’s relatives. Husband Fred had been joined in jail by his 15-year-old son, Alton. There was something people found fishy about the youth, a husky boy standing over six feet tall but always mumbling without fully opening his mouth. Earlier that year a judge had committed Alton to an institution in Salem, but it had been too crowded to receive him; reporters were quick to quote reports calling him “feebleminded” and of an “unlikeable disposition.”

May sat down with the boy. He watched Alton talk, listened to him, gathered the sketches the boy was making on scrap paper of women with flapper haircuts. The boy wasn’t mentally deficient, May decided. Alton just couldn’t hear well.

But Alton still wouldn’t explain what had happened on Labor Day. He insisted that he’d milked a cow that morning and that his sister Lucille ate her usual mush toast and cocoa for breakfast. It was clear to May that both father and son knew more than they were sharing, but who was covering for whom?

Image: Courtesy MOHAI

May found letters from Fred’s older children that proved they disliked Ebba; he paged through correspondence just a few months old where teenaged Lucille complained, “What our dear moma liked and was happy with is not good enough for this high horse.” After the murder, Ebba’s parents took in her three small children. Lucille was sent to a neighbor’s and Fred’s brother Arthur, in a wheelchair with no one to care for him, was moved to the county poor farm.

“Who would benefit by death,” wrote May in his loopy hand on notepaper as he tried to ascertain motive. His plausible answers: Arthur, who hated Ebba. Teenaged Alton, who didn’t like her either. Lucille, “who would become mistress of house and who was chafing under stepmother’s rule.” As he worked the case out by hand like a long division problem, May came to a conclusion: There was no motive for Fred.

Had Luke May been the type to take someone else’s work as fact, he wouldn’t have traveled 400-some miles from Seattle to Bandon by the Sea. But he wanted to see the body—and face—of Ebba Covell for himself. He arranged for the body to be exhumed and, early in the afternoon of September 12, in a local undertaker’s parlor, examined it with the help of a local doctor.

Despite the murder, despite a week in her grave, you could still see how Ebba, about 30, had been rather pretty before, her thin face framed by thick brown hair. But now bruises dotted her skin, and a “livid discoloration” spread across her face, dark and hardened to a leathery consistency. It looked like a spatter of black ink, covering everything from the bridge of her nose down, her nose a solid black and her cheeks painted in streaks. Even her front teeth were stained.

As ever, May’s scientific mind cataloged every possibility: Were her wounds of her own making? Could this have occurred via natural causes? Was she hit with an object, or did she hit the floor? Could the stain on her face—ammonia, he deduced—have been self-inflicted?

Ebba’s neck, notably, was not broken.

May wasn’t prone to referencing his fictional doppelgänger, but his work could have been summed up by Sherlock Holmes’s famous adage: “When you have eliminated the impossible whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” Having ruled out sudden illness or fatal poisoning, the only solution was suffocation.

May interviewed Fred Covell and found no evidence that the unhelpful, oft-married chiropractor was to blame. With the initial suspect dismissed, what May needed were more clues.

They came, prosaically enough, on paper. First there were the letters from Lucille, passionate with the fury only a 14-year-old can muster.

May called her “not overbright” but noted the letters she was writing to the officials holding her brother in jail. “Why don’t you open your eyes and see things?” she wrote in round, childish cursive. “I could be a better justice of peace and officers than any of you people.”

And then back at the farmhouse, more papers. May leafed through Arthur Covell’s diary, looking at the entry concerning the day of the murder and finding an odd note “Made a mistake. Con. wrong—should have subtracted 14 minutes for this latitude and longitude.”

Image: UW Special Collections and Seattle Met Composite

Arthur’s puzzling diary entry was in fact related to the man’s hobby: astrology. Despite being largely bedridden after a car accident, Arthur wrote out star charts, making predictions and conclusions for people based on birth dates and places, determined by the positions of star constellations.

The supernatural was, in the 1920s, having a moment. It was a rollicking decade that could give the 2020s a run for their money when it came to postpandemic madness; amid the Prohibition and Jazz Age partying swelled America’s long obsession with spiritualism. Scholars would later reason that the horrors of World War I and the Spanish Flu drove fascination with the mystical. Mediums and soothsayers spoke of life after death, weaving scattershot touches of Eastern culture, dangling the promise of meaning beyond the horrors of modern life. And in Oregon, Arthur Covell was making a career of ascribing cosmic power to unseen forces.

Not everybody believed in that promise. Luke May himself lived in the world of the tactile, the provable. In the 1920s Harry Houdini turned from practicing his own magic to debunking astrology and those who claimed to talk to the dead; in 1926 a New York congressman would propose a federal bill to criminalize fortunetelling in Washington, DC.

But Arthur Covell did astrological charts for Hollywood actors, his writings speaking to the belief in an underlying power that fed the universe, the country, and the individual. They spoke of rising above: The moon in Virgo “confers much talent of a high order.” Mars and Uranus together suggest “the possibility of some benefit accruing to you.” Like so many who trafficked in supernatural insight, what Arthur really delivered was flattery and possibility.

May dug into one of the boxes Arthur had left in care of a neighbor when he was moved to the poor farm. The star charts were broken into 12 wedges, leaving spaces for basic facts—name, birth details, color of hair. Covell’s markings around the charts were mostly non-English symbols, like letters reimagined as doodles, the language of astrologers. But the same symbols appeared in unintelligible notes in Covell’s box, correspondence made of loops, crosses, squares, or even letters in confusing and unreadable combinations.

It didn’t take long for May to realize he was looking at a secret code.

How do you catch a thief, a rapist, a murderer? The detective must pluck an invisible thread that ties the crime to the criminal, then build a delicate narrative of facts and clues that prove a suspect is without a doubt guilty. But in the 1920s, police didn’t even always know to look around the room or list the items found in a dead person’s pockets.

To pluck the kinds of invisible threads required of him, Luke May couldn’t be a specialist. He gained proficiency in almost every kind of detection and analysis known or being developed in his era. He solved cases by analyzing handwriting, blood spatters, toxicology, and ballistics. He could analyze the tool markings on a tree to link a person to a crime and tell whether a gunshot wound meant suicide.

His analytical prowess extended into human behavior, his writings categorizing just how to interview suspects, eyeball a crime scene, and identify corpus delicti. May went undercover himself, and owned a button camera that looked like something out of a steampunk fantasy—a giant metal contraption he could wear under his shirt to take surreptitious photos through his literal buttonhole. “He ate, breathed, and drank sleuthing,” says Seattle Police Department retiree and unofficial SPD historian Jim Ritter, who today holds some of May’s artifacts.

Fingerprints were first described for crime identification in the 1800s, but by the early twentieth century their use was still uneven. May developed his own fingerprint powder to detect them but also figured out how fingerprints could be faked. He once used a black light to prove that a typewritten contract had been altered. May wasn’t the only one building this nascent, desperately needed field of criminology, but he did it with vigor.

In 1922, May invented his Revelaroscope, named, of course, for his agency; The Seattle Times dubbed it the “Mastodon of the Microscope Family.” The 400-pound microscope could enhance detail in large form; even in his twenties, May was already having eye trouble from doing repeated examinations. The Revelaroscope has since been lost to history after sitting in a Pioneer Square surplus shop for decades.

Image: Courtesy Mindi Reid

For all his technological advances, May’s greatest legacy may have been organizational, educational, even institutional. He helped launch the Northwest

Association of Sheriffs and Police, which then opened its own Northwest

College of Criminology. He authored articles and books on how to investigate; one pocket-size field guide to criminology included lists of questions to ask about a given crime, and some 159 different types of physical evidence to look for (string, dust, textiles, but also receipts, wastepaper, and timepieces) and a list of possible motives (“7. Revenge; 18. Fear of exposure; 24. Insane desire to kill”).

What’s more, he pressed upon his colleagues that every case could be solved, that no crime had ever been committed that did not leave behind a clue. And in 1933, Seattle’s consulting detective entered the fold, at least for a little while. After Seattle Police Department’s chief of detectives died unexpectedly, May was given the title, registered as a special officer. He dismantled the detective division, keeping only those who were willing to go out and investigate his way—in person, thoroughly, systematically. May stayed with the SPD for only 14 months, annoyed by the lack of budget and support.

But even after he left the force, May’s instructional era continued, if slightly less formally.

When True Detective Mysteries magazine would arrive in the May household mailbox, Helen May would tear off its lurid covers. She was repulsed by the shocked-looking women in low-cut dresses and pistols still wafting with smoke, headlines screaming of murder and violent passion and bandits. But she kept the printed magazine underneath; it was her husband’s de facto classroom.

Inside every issue of True Detective Mysteries was Luke May’s Department, his own regular section of the magazine. Under a photo of May posed behind his ever-glossy desk, talking into a Dictaphone, the article ran as a Q&A, in which May responded to inquiries about ballistics or debunked phrenology as a science. Reader letters were to be sent to the Capitol Hill address, marketed on the page as Scientific Detective Laboratories.

Image: Courtesy Mindi Reid

Other articles inside the magazine told the tales of his cases, most with anguished descriptions of crime scenes using language that would never have come from the staid May’s mouth. He proofed the stories of his famous crimes that appeared in print, often correcting another writer’s grammar even as they fictionalized his crime-catching work.

No matter how sensationalistic the headlines, May reasoned, the magazine stories served as teaching tools—and maybe even a warning. May’s granddaughter, Mindi Reid, remembers his hope that the stories “would be a deterrent [to] people who might be inclined to do bad stuff,” she says, lest they think they were clever. “Science is cleverer still.”

As with most adults of the time, May’s life was interrupted by World War II. He had been commissioned as a lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve Corps in the 1930s, and through the end of that decade worked with naval intelligence, lending his expertise on informant networks. He was called into active duty in October 1940, and he was promoted to commander. For the next four years, he trained agents on investigative methods and intelligence issues.

After the war, everything was different, and that included the private investigation business. For years May had lobbied for police departments to have their own in-house crime labs instead of outsourcing the work to people like him; the decade after the war would see that become a reality. Criminology schools were forming, like the pioneering program at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1950.

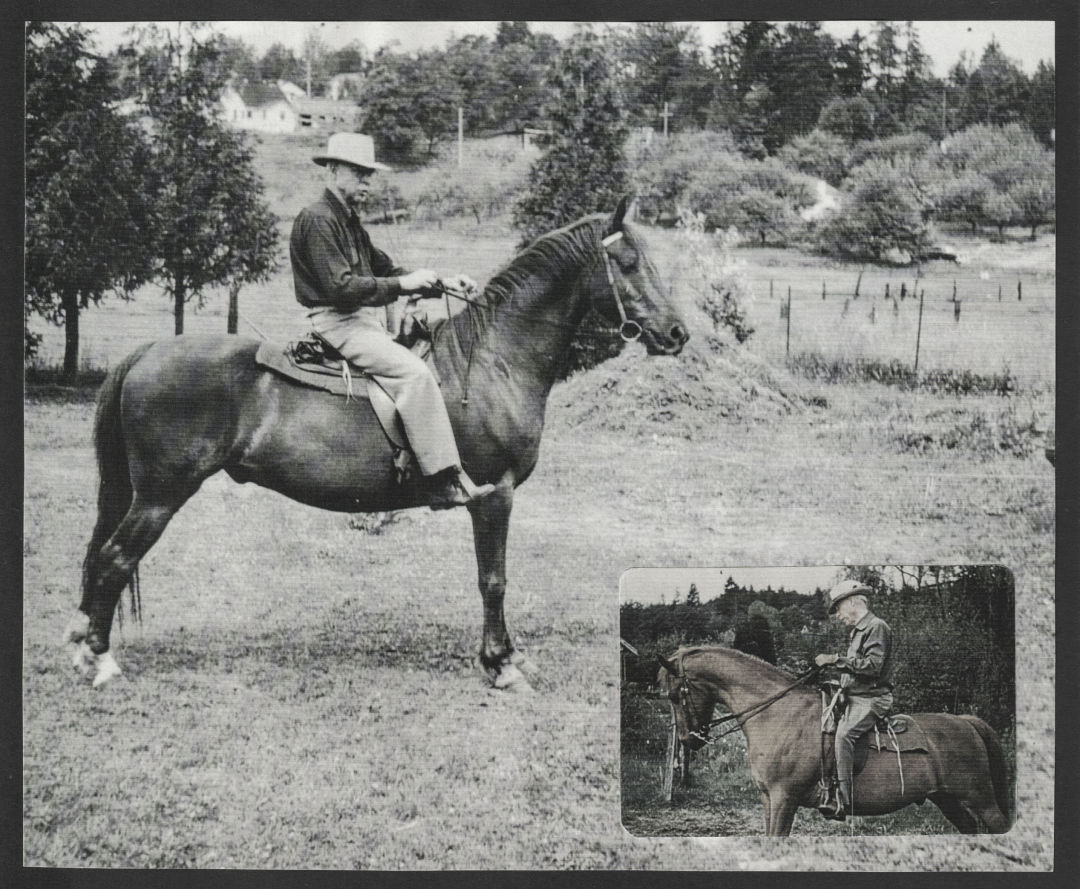

May pivoted to document work and lie detector expertise. He still worked cases, but fewer murders and even fewer high-profile cases. He embraced horseback riding and made real estate deals; he liked watching professional wrestling. A producer approached him about turning his cases into a TV show in the style of Dragnet, but it never came to fruition.

Image: Courtesy Mindi Reid

May and his wife sold the Capitol Hill mansion and moved to a more modest home in Wedgwood, and eventually he retired altogether. Before he died in 1965, he gave his granddaughter, Mindi, a magnifying glass for her fourth birthday.

Today many of May’s files sit in the Special Collections of the University of Washington library. As the keeper of her grandfather’s legacy, Mindi lets scholars and researchers page through boxes of yellowing papers and scribbled notes, mimeographed correspondence and newspaper clippings.

The man who unburied secrets, who devised clever ways to expose them, died with a few secrets of his own. While his files were cataloged, Helen destroyed one chunk of her late husband’s work. It wasn’t until much later that the rest of his family learned what it likely was: records of another daughter from an earlier marriage, relinquished to the state in the early 1920s. There’s no way of knowing how many other mysteries Luke May took to his grave.

Image: Courtesy Mindi Ried

A few years before he died, May went to the Seattle World’s Fair. Mindi still has a photo of her grandfather in his signature hat, posing with his wife, daughter, and tiny Mindi herself under the soaring cabins of the Skyride aerial tram that crossed Seattle Center. When May set up shop in rough-and-tumble Seattle in 1919, it was hard to imagine the city coming to stand for science and progress. But in 1962, the Science Pavilion had a large model of Watson and Crick’s newly discovered DNA molecule, the one frontier of science, of criminology, that he just barely missed. If he’d lived a little longer, May would probably have become a self-trained expert in that too.

In Oregon, May had determined what hadn’t happened to Ebba Covell; now for what really did. Paging through Arthur Covell’s bizarre hieroglyphic paperwork, he saw the names of Bandon locals and more astrological symbols. To a mind like May’s, Arthur’s cipher code wasn’t hard to break. What was more stunning was what the gibberish notes ended up saying.

“A total of twenty-nine murders had been carefully planned” by Arthur Covell, May later wrote about the case. The murders were organized by the star signs, scheduled for when astrology said was favorable. Ebba Covell’s star chart was among the papers. More prosaically, the notes contained details for the actual perpetrator: young Alton.

It seemed clear now that Arthur had been the brains behind Ebba’s murder while his nephew, Alton, had done the dirty work: an impressionable teen steered by an astrologer with a shifting grasp on morals, fueled by a belief that the stars spelled out his destiny. The only problem was that neither Alton nor Arthur would talk to May.

The detective started with Lucille. She would often visit her brother in jail and whisper desperately, their conversations picked up by spy equipment. Then May intercepted letters being passed from Arthur to Alton. Scribbled on page 60 of a copy of The American Magazine passed to the boy, Arthur instructed him to “deny that I told you to kill her. Deny that you did kill her.” Other notes were passed to Alton on toilet paper or crammed inside an apple.

A plan coalesced. May’s procedural brain could negotiate more than microscope slides, and he constructed a plan. A sneaky, manipulative one. He’d plant a misleading headline in the newspapers and shake a confession out of young Alton.

The newspapers complied. In the Coos Bay Times on October 9, the top of page one read “Arthur Covell Confesses He Planned Crimes.” Though the small print in the story noted only that the uncle’s papers had spelled out other, as-yet-uncommitted crimes, with “no direct connection with the death of the woman,” May let the imprisoned Alton read just the headlines. “I didn’t care to let him know just what his uncle had confessed,” he wrote.

Alton himself confessed to May that afternoon. He described how he used a rag soaked in ammonia to cover his stepmother’s face for three minutes, how he threw it in a gulch after. His sister and his uncle had known about it, he said. His uncle had directed him. It didn’t take May long to get a confession from Arthur, and the astrologer handed the grand jury foreman a statement the next day, claiming responsibility for it all.

Though Ebba’s murder had received little attention in the news at first—just a rural housewife found dead—the twists May uncovered made it all front page–worthy. “Stars Spelled Her Death,” read one. “Astrologer Confesses to Murder Plot” ran the full banner headline in the October 12 edition of The Portland News. The planned, uncommitted crimes were even more bizarre than the one that had taken place, and the true crime circus that ensued would have exhausted Nancy Grace.

And Luke May, criminologist, was usually given credit.

All that remains of Luke May’s time in Southern Oregon are a scattering of notes and a sheath of professional correspondence—plus the always unreliable testimony of the popular press. The newspapers of the day got facts wrong as a matter of course, bungling names, vacillating the date of the murder by several days, and fumbling who knows what else. In his own book, Crime’s Nemesis, May would contradict the news reports, his own notes, and the thrilling tale he’d OK’d for the magazine. May cared about the science he doled out in his advice column, not the narrative submitted to history.

Image: Courtesy Mindi Reid

As weeks went on after the confession, it became clear that Arthur held an unbelievable hold over his niece and nephew, both of whom had lived with him for a time. Lucille showed up at the trials dressed in flapper wear, impressing the media with her adult appearance. But once on the stand, May wrote later, the girl was unable to incriminate her uncle unless District Attorney Fisher blocked her views of him. Fisher obtained a guilty verdict for Alton; he’d serve about a decade before going free. Arthur was convicted of murder in the first degree and was executed by hanging in May 1925.

Arthur claimed that Alton and Lucille “were at all times under control of my mind and will.” They’d fallen under the thrall of a man with the urge to wrest power into his own grasp, first the power of celestial forces and then, more acutely, the sheer physical power of a teenage boy to do his bidding. Arthur Covell thought he’d picked the perfect time, by the stars, to commit his crime. But he didn’t operate with the rigor of Luke May.

The final story of what happened when May wrapped up the Covell case—the Murder by the Stars—might be true. Or it might have been the romantic fantasy of a reporter juicing his story, a tale adopted by May himself in later writings. It goes like this: As May left Arthur Covell’s trial, the murderer reached up from his cot to shake Luke May’s hand and tell the man who outsmarted him one last thing: “You only did your duty.”