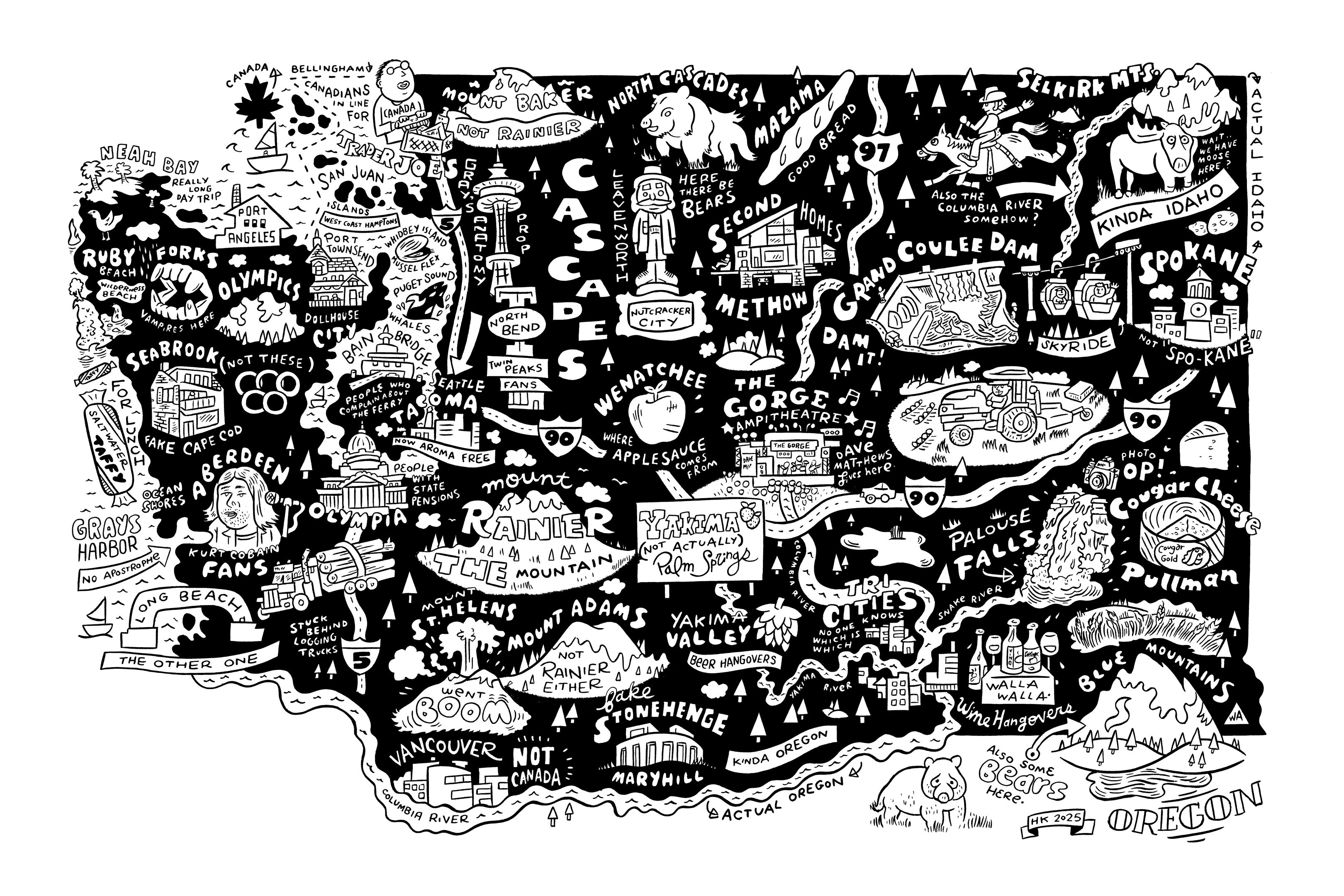

This Washington

State Reps, AG's Office Accuse ACLU of Misinformation on Gang Bill. ACLU Stands by Claims

There was a tense moment during yesterday's public hearing on state Attorney General Rob McKenna's controversial gang bill

.

After ACLU lobbyist Shankar Narayan testified against the bill—the ACLU is concerned that the bill gives elastic leeway to law enforcement to label someone as a gang member—state Rep. Kirk Pearson (R-39, Monroe) had a combative question for Narayan: "Do you stand by the emails [ACLU supporters] sent to us about this bill? Are you aware that there were inaccuracies in the emails?"

After Narayan said he stood by the ACLU's interpretation of the bill, the Democratic chair of the committee, Rep. Chris Hurst (D-31, Enumclaw), concluded the tense moment, saying he too was "concerned" about the emails.

In part, the ACLU emails state: "This approach [legally labeling suspects as gang members] will sweep up innocent people and order them into court where they will have no right to an attorney and no realistic opportunity to show they are not gang members."

Here's the deal: The bill allows law enforcement to seek a "protective order" against an alleged gang member. The provision was modeled, the AGs office says, along the lines of a domestic violence protective order, where, indeed, the respondent (the alleged abuser), doesn't have a constitutional right to an attorney. (In the AGs analgoy, the community at large is the abused partner).

The city has to show "by clear and convincing evidence" that a criminal gang exists and prove that the suspect is a member. Once the protective order is granted, the alleged gang member can be prohbited from a long list of activities, including: violating curfew, wearing gang clothing, intimidating people, associating with other gang members, possessing alcohol, and carrying weapons.

If they blow it, they're arrested for violating the protective order; or as the ACLU complains, a person with no previous record is set up to have a record.

Proponents of the bill like Pearson and Hurst (and the AGs office) scoff at the notion that bill doesn't allow alleged gang members the right to an attorney.

AG spokesman Dan Sytman responded to the emails with an email of his own:

Sytman also belittled the ACLU "robo mails," saying that in some instances, when legislators tried to respond to the emails, they bounced back because there was no known sender.

Narayan tells PubliCola the fact that an attorney isn't required to get a protective order is excactly why the AG's equation is "so problematic."

Narayan also has trouble with the AG's analogy to domestic violence. He says,

After ACLU lobbyist Shankar Narayan testified against the bill—the ACLU is concerned that the bill gives elastic leeway to law enforcement to label someone as a gang member—state Rep. Kirk Pearson (R-39, Monroe) had a combative question for Narayan: "Do you stand by the emails [ACLU supporters] sent to us about this bill? Are you aware that there were inaccuracies in the emails?"

After Narayan said he stood by the ACLU's interpretation of the bill, the Democratic chair of the committee, Rep. Chris Hurst (D-31, Enumclaw), concluded the tense moment, saying he too was "concerned" about the emails.

In part, the ACLU emails state: "This approach [legally labeling suspects as gang members] will sweep up innocent people and order them into court where they will have no right to an attorney and no realistic opportunity to show they are not gang members."

Here's the deal: The bill allows law enforcement to seek a "protective order" against an alleged gang member. The provision was modeled, the AGs office says, along the lines of a domestic violence protective order, where, indeed, the respondent (the alleged abuser), doesn't have a constitutional right to an attorney. (In the AGs analgoy, the community at large is the abused partner).

The city has to show "by clear and convincing evidence" that a criminal gang exists and prove that the suspect is a member. Once the protective order is granted, the alleged gang member can be prohbited from a long list of activities, including: violating curfew, wearing gang clothing, intimidating people, associating with other gang members, possessing alcohol, and carrying weapons.

If they blow it, they're arrested for violating the protective order; or as the ACLU complains, a person with no previous record is set up to have a record.

Proponents of the bill like Pearson and Hurst (and the AGs office) scoff at the notion that bill doesn't allow alleged gang members the right to an attorney.

AG spokesman Dan Sytman responded to the emails with an email of his own:

"As the ACLU knows, appointment of counsel at a protection order hearing is not constitutionally required because the protection order hearing is a civil hearing. This is how anti-domestic violence and anti-harassment protection orders work. This protection order statute is identical to all other protection order statutes in Washington in that none of them require court appointed counsel at the protection order hearing."

Sytman also belittled the ACLU "robo mails," saying that in some instances, when legislators tried to respond to the emails, they bounced back because there was no known sender.

Narayan tells PubliCola the fact that an attorney isn't required to get a protective order is excactly why the AG's equation is "so problematic."

The subject of the injunction is unlikely to be able to fight back even if they are not a gang member, because they have no attorney at that stage.

After that stage, a custom-tailored trapdoor has been created that the individual is likely to violate simply by living his life -- and resulting in a criminal charge that he is unlikely to be able to defeat even though he will have an attorney at that stage.

Narayan also has trouble with the AG's analogy to domestic violence. He says,

In a DV protection order, you have evidence for the potential for specific behavior, physical violence. In a gang injunction, you have the potential for unspecified behavior—remember, injunctions don't require any crime to happen, just that a gang exists and this person is a member—by an individual [where] little or no evidence may exist other than their dress and associations, against 'the community'. So the point is that this kind of net is so broad that an attorney should be required."