The Man Who Loved Seattle Too Much

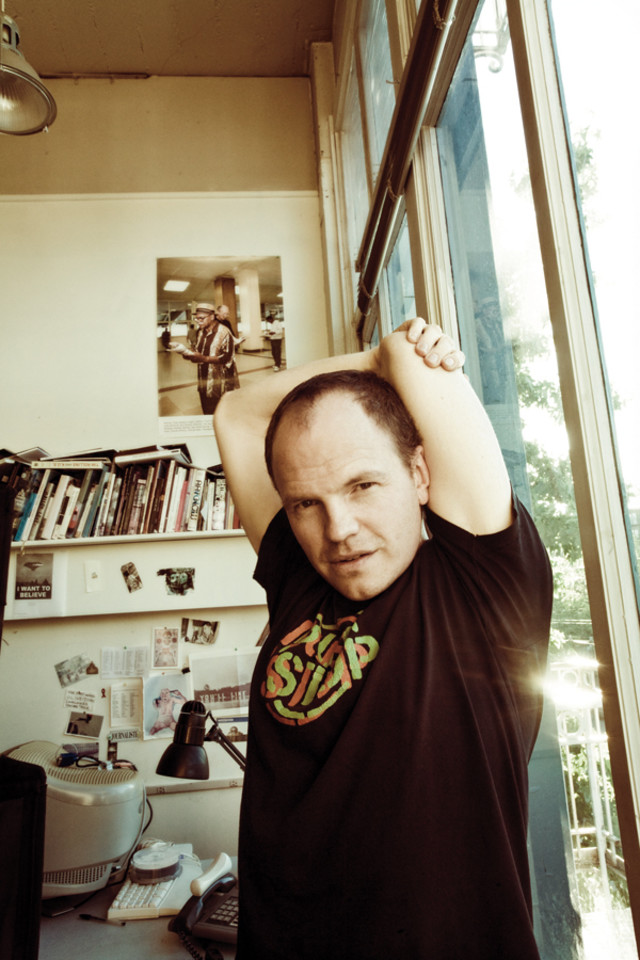

Image: José Mandojana

SCENE 1: THE WRAP PARTY

It was a night of tears, cheers, and bear hugs. After two months of careering around town, Grassroots, the new film about an improbable Seattle City Council campaign in 2001, had finished shooting. It was time for that fraught but inevitable movieland ritual—the wrap party.

The love and praises flowed, celebrating a rare event: a nationally produced film set in Seattle that was actually filmed in Seattle. But one figure stood apart, as distinct as a polar bear on Puget Sound. Amid the T-shirts and cocktail dresses, he wore a black watch cap and Michelin-man jacket. His face was red and his expression a rush of flickering emotions. He clutched a glass of brandy like a buoy in a storm.

This was Grant Cogswell, the poet-turned-activist-turned-politician-turned-filmmaker whose 10-year struggle to make Seattle a more urbane, communitarian, and transit-friendly city in the 1990s and early 2000s rocked local politics, nearly wrecked his own life, and inspired the book that inspired Grassroots. He’d traveled 2,800 miles from his current home in Mexico to attend and try to capitalize on the film’s making. He’d dropped in on shooting, been filmed himself for a companion documentary, enlisted Mayor Mike McGinn for one scene, even played a city councilman (not himself) in another.

The 2001 city council campaign was one minor chapter in a torturous decade for both Cogswell and the city he embraced. To watch others reenact it was “very, very weird,” he told me. “Uncanny in the original sense of the word.” Then he brightened. “Stephen [Gyllenhaal, the director] said it’s comforting when people see their pain being made into a film. It’s distancing, it takes it outside of them. And he was right. It put that whole period outside of me. It’s like sending your life off to the cleaners and having it come back better.”

ALTERNATE REALITIES

Life, only better, is Hollywood’s implicit promise: Forge a happy ending, or an uplifting tragedy, out of stories that in real life just dribble or fade away. No one understands this better than a veteran director like Stephen Gyllenhaal. He made several powerful but underappreciated films in the ’90s, then swore off features and stuck to directing TV shows. An editor at Nation Books sent him Zioncheck for President: A True Story of Idealism and Madness in American Politics —a picaresque memoir of Cogswell’s 2001 run for office by his campaign manager and (then) friend, Phil Campbell. The story of Cogswell’s insurgent candidacy, conceived to help Seattle rise above its car addiction with a high-flying monorail system, electrified Gyllenhaal. He saw Campbell and Cogswell as heroic figures: “Like Rocky: The characters are everyday little guys scurrying around in the shadows of a beautiful city, challenging the status quo.” Not only that, they had the makings of that Hollywood staple, the buddy picture—and, as played by Jason Biggs (Jim in the American Pie movies) and Joel David Moore (the overwrought scientist in Avatar), of a classic comedy duo.

All of this meant improving the facts that Campbell had scrupulously recorded in Zioncheck for President. Far from a Hollywood bromance, the arduous campaign actually ruptured Campbell’s and Cogswell’s friendship.

Cogswell looks nothing like the tall, gawky Joel David Moore. He can be intense and abrasive, but he stayed cool and poised throughout the campaign, at least in public. Moore’s version is an idealistic goofball, a shoe-pounding, profanity-spewing eruption of righteous passion. He delivers a stirring post-9/11 speech that Cogswell never gave. He even storms about in a polar bear suit at a rally and a city council meeting—something the real Cogswell only joked about doing if he were elected. It becomes the movie’s signature image.

“So did you really have a polar bear suit?” one guest at the wrap party asked Cogswell. “I’m deferring all questions to the director,” Cogswell replied, nodding at Gyllenhaal. “It doesn’t matter what really happened,” said Gyllenhaal. “We’re making myths here!”

{page break}

In Grassroots, the actor Joel David Moore dons a polar bear suit, something Grant Cogswell threatened but never did.

Image: Hilary Harris

THE IMMIGRANT

Gyllenhaal is late to this game. Grant Cogswell has been creating—and living—the myth of Grant Cogswell for decades, trying to write his own happy ending, or ennobling tragedy. So powerful was his mythopoeic conception of his life that for a while he was able to embrace an entire city in it.

Cogswell was born in Los Angeles to a family marked by what he calls “a potent confluence of political passion and madness”—twin specters that would haunt him as well. His grandmothers met while working on a legislative campaign. His mother worked on Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign and was at the Ambassador Hotel when Kennedy was shot. His maternal grandfather was institutionalized “in his late 60s.”

His father was a globe-trotting tech rep for an aerospace company and a prodigious drinker. His mother fled the drinking when Grant was four, and his father took him along, shuttling between European hotel rooms. He spent his high school years in England. Only much later did his mother tell him Dad also worked for the CIA.

Growing up transient and motherless “was hell,” says Cogswell. It induced an expat’s sense of displacement and an abiding yearning to belong somewhere: “He was one of the loneliest people I ever met,” Campbell wrote. When Grant was nearly 17, the family returned to Los Angeles, an experience he found “horrific.” He’d grown up hearing idyllic tales about the LA of streetcars and orange groves, nothing like the smog-choked sprawl he returned to.

But one place beckoned as a haven of calm and continuity. When Grant was 12, his grandmother moved to Mercer Island, and he spent each summer there, reveling in the trees, mountains, and smogless skies.

THE LEGACY

Cogswell moved to Seattle in May 1994, after college (creative writing, classics, and English). He was finishing a novel, since shelved; he had a passion for punk rock, a protean sexual identity (he’s variously identified himself as gay, bi, and straight; the significant relationships he talks about were with women), and a Europe-influenced vision of urban community he thought Seattle might still fulfill. “Seattle then was LA in 1952…. I thought we could still turn the tide.” Still get it right. Still write a happy ending to Los Angeles’s story, elsewhere.

He reread Murray Morgan’s Skid Road, the lively collection of vignettes that has introduced generations to Seattle’s history. In its pages he found a soulmate: Marion Zioncheck.

Like Cogswell, he was an immigrant outsider touched with brilliance. He worked from childhood on, putting himself through the University of Washington by logging, sandhogging, selling papers, and catching fish and (for the health authorities) rats. A rousing orator, he got elected student president, then challenged the college’s most sacred cows, Greek Row and the athletic department. He urged redirecting funds from sports teams to a student center. Jocks shaved his head, roughed him up, and tossed him in Frosh Pond, but Zioncheck didn’t back down. Two decades later the Husky Union was built.

Soon after law school, Zioncheck scored a populist triumph: leading a successful recall drive against Mayor Frank Edwards, who wanted to sell off Seattle City Light. He then ran for Congress, and in 1932, at the age of 31 and to everyone’s surprise, he won.

At first Zioncheck backed President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. But he soon grew disillusioned—“like an Obama volunteer who doesn’t vote in 2012 because he’s disappointed,” says Cogswell. Zioncheck led an insurgent congressional left bloc that tried to boost taxes and support public education. He drank and worked ferociously, reading every bill that came before Congress. Overwork, Cogswell believes, drove Zioncheck over the edge. That and caring too much.

Zioncheck cracked up in style midway through his second term. On January 1, 1936, after carousing through the night, he lurched up to the switchboard of a Washington, DC, apartment house, plugged in all the lines, and wished everyone a happy New Year. Arrested and jailed, he sobered up, but not for long.

Updated September 22, 2010. This version corrects errors originally published in the October 2010 issue. Grant Cogswell’s mother worked on Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential, not congressional, campaign.

{page break}

Marion Zioncheck (above left), like Cogswell, was an outsider touched with brilliance and a passion for politics.

For the next six months, Zioncheck’s capers made him a darling of the scandal sheets, who dubbed him “the playboy congressman” and stalked him obsessively. He collected and ignored speeding tickets, and had to be stopped from brawling with a Texan delegate on the House floor. He married a federal typist after one date; she left him, then came back. Straightjacketed away to a sanitarium, he escaped and returned to Seattle. He announced he would seek reelection, then changed his mind and withdrew his candidacy, then decided again to run.

Image: Hilary Harris

On August 8, 1936, Zioncheck was to give a speech in -Seattle. He stopped by his office in the Arctic Building to pick up some papers. His brother-in-law entered the office and found Zioncheck scribbling at his desk. Zioncheck jumped up, dashed to the window, and plunged to the pavement. The note he’d started read, “My only hope in life was to improve the condition of an unfair economic system that held no promise to those that all the wealth of a decent chance to survive let alone live.”

To Cogswell, Zioncheck’s life seemed to embrace his own contradictions: his social conscience and impish exhibitionism, ardent energy punctuated by paralyzing bouts of depression—that familial “confluence of political passion and madness.” He began writing an “Ode to Congressman Marion Zioncheck.”

Cogswell worked on it for six years, till it reached epic length.

Marion Zioncheck for President

of Death!

is my new campaign: your plea

wins just one vote in this house,

my own….

Phil Campbell took his title from the poem and seeded the book with Zioncheck’s story. But there’s no room in movie comedy for the ghosts of Congress past, and no Zioncheck in Grassroots. Just as well, says Cogswell; he’s writing the movie he wants to make about Zioncheck. Cogswell found a cautionary example, even a type of hope, in his doomed hero’s despair. He would face the world, even when he likewise felt buffeted by it. He would fight, but stop when the fight could no longer be won. By surviving, he would write a happy ending to Zioncheck’s story.

MORE IMPORTANT THINGS

Cogswell entered the political fray just as Zioncheck had: via a ballot battle to protect public resources from private interests. Around the time he landed in town, the Mariners and Seahawks began demanding new stadiums to replace the dowdy but functional Kingdome. An opposition group, Citizens for More Important Things, formed, and Cogswell became its field coordinator. In late 1996 he began an all-volunteer petition drive that collected a record 74,000 signatures in two months for an initiative that would ban public funding of pro-sports facilities—a stunning upset. “It wouldn’t have happened without Grant,” says Chris Van Dyk, the campaign’s founder. “He was everything you could hope for in a political activist—committed, methodical, organized, able to live on next to nothing. He’s one of those rare people who come out of nowhere, take on anybody, and can do anything.”

Almost anything. In the end the team owners won. The legislature overrode county voters and funded the baseball stadium. Paul Allen, the Seahawks’ new co-owner, spent $3 million on lobbying and $8.4 million on a special election for a football stadium.

The campaigns wore hard on Cogswell. Some sports fans bitterly resented the challenge to their beloved teams. “I was getting death threats all the time,” he recalls. “I stopped listening and tried to put it out of my mind. I guess I didn’t really—it stayed in my body.” He started getting severe pains in his back, then hips, legs, shoulders, and feet. He couldn’t stand cold; the watch cap he often wears in summer is not an affectation. “Doctors were baffled,” he says. “I think it’s stress-related.” The symptoms, vividly caricatured in Grassroots, recurred as long as he stayed in Seattle.

MONORAIL MEN

At Bumbershoot 1994 Cogswell saw a garrulous bear of a man named Dick Falkenbury desperately flogging a petition to build a monorail system. Falkenbury, then a chatty, polymath taxi and tour-bus driver, came to a realization while navigating traffic: Seattle didn’t just need transit. It needed elevated transit, which wouldn’t block or get bogged down in traffic, nor divide neighborhoods with dangerous railways as would the surface light rail the official powers wanted to build. And monorail, unlike rail, could climb Seattle’s steep hills, eliminating costly tunnels.

{page break}

Cogswell “understood the idea immediately,” says Falkenbury. And he understood why Falkenbury’s amateurish effort was fizzling. He enlisted in it, cleaned up Falkenbury’s sloppy writing and signage, and honed his message. He invented an ingenious, low-tech automated alternative to the usual prerequisites for a successful petition, an army of volunteers or money to pay signature gatherers. Instead, Cogswell devised four-by-eight-foot plywood easels on which literature and petitions could be set out for passersby to read and sign at leisure.

“It doesn’t matter what really happened. We’re making myths here!”

“Grant’s the kind of guy who will have 100 good ideas—and one of them will be just the right idea,” says Falkenbury. “This one was brilliant!” It was too late to gin up support for ’95, but they launched a new petition drive in 1996 (in between Cogswell’s two stadium campaigns), swept onto the September 1997 ballot and passed with a healthy 6 percent margin.

The New York Times called the monorail victory the Northwest’s “biggest political upset” in a decade. Cogswell celebrated by getting the city seal tattooed on his shoulder. It was a grandiose gesture, and a commitment: From now on Seattle was his, and he was Seattle’s.

Actually building the monorail was another matter. Vultures charged with implementing it loomed in the city government, waiting to pick it off. In 2001 Cogswell decided to unseat one of them.

THE SCRIBE

Phil Campbell arrived from Memphis in August 1999 to take a job as a reporter at The Stranger. But he didn’t get Seattle. Its big-cause activists left him bewildered and suspicious, and the anti-WTO protests three months later blindsided him. Then, looking up through the tear gas, pepper spray, and flash grenades he saw “a two-wheeled apparition”: Grant Cogswell, a freelance music critic for The Stranger, speeding with fierce, expert determination through the chaos.

Cogswell became Campbell’s Virgil, guiding him through the mysteries of Seattle’s soul. Still, Campbell lacked the right snarky edge for The Stranger, and in June 2001 the paper fired him. Campbell was despondent, but Cogswell revived him with an audacious idea. He was going to run for city council, against transportation committee chair Richard McIver, a key monorail opponent. And he wanted Campbell for his campaign manager.

The rest is history, as recorded in Zioncheck for President and reimagined in Grassroots. Cogswell lost, but won 45 percent of the vote against a popular incumbent, the only African American on a council that had for decades had a semi-dedicated “black seat.”

Supporters and political pros urged Cogswell to run for an open seat next time around. But he was done with electoral politics. Campbell was deeply disappointed: Cogswell was throwing away all their labors, squandering his chance to actually change the system.

“I didn’t give up because I lost,” says Cogswell. “I gave up because I saw it was a place where I wouldn’t be able to get anything done…. Zioncheck was a great warning sign, though of course I didn’t see it at first. I realized I had to stop.”

LITTLE VICTORIES

Cogswell resumed campaigning for issues rather than office. For about one year, starting in 2002, he became Executive Director of Yes for Seattle, a nonprofit promoting select urban—environmental initiatives. The first two, for water conservation and creek restoration, succeeded so well that they never made it to the ballot: City Hall enacted versions of them.

{page break}

Afterward he helped launch one more big fight. In 2004 he and urban designer Cary Moon started a campaign for a highway-free downtown waterfront: no viaduct, no tunnel, more transit. Cogswell crafted the message, the name (the People’s Waterfront Coalition), and a waterfront vision: the Seattle Strand, a shore and a bejeweled string, strung with parks instead of pearls.

Their effort transformed the public debate. In a three-way advisory vote, Seattleites preferred the no-highway option, eventually forcing the state to back off demanding a new viaduct and settle for a compromise tunnel. Moon, who’s still fighting the tunnel plan, has gotten the public credit. But she says Cogswell’s work was invaluable: “We’ll realize much later how much he contributed to the city.”

THE HORROR

At the same time Cogswell launched a very different but likewise audacious project. An old friend named Dan Gildark, now studying filmmaking in Portland, asked him to write a screenplay. Cogswell set aside his dream of a Zioncheck film and dashed out Cthulhu, a “Gothic, apocalyptic, anti-Bush, gay horror” feature derived from H. P. Lovecraft and set in a fictionalized Astoria, with undertones of his own haunted family history. He sold his condo, poured in $140,000 of a family inheritance, and, his persuasive powers undimmed, lured more investors—plus Tori Spelling, to play a scary seductress.

Meanwhile, the monorail fight dragged on. After voters passed Falkenbury and Cogswell’s 1997 initiative, the city council stonewalled. Proponents sued to force the council to act; it responded by repealing the initiative. Voters then passed two more initiatives reinstating the monorail plan, and overwhelmingly rejected a 2004 measure to scuttle it. But the project got saddled with bloated costs, a compromised route, feeble taxing capacity, and fatally expensive financing. Cogswell by then had no official role. “But I was still trying to shepherd it along,” he says. “My heart was completely invested in it.

“I knew it was over when I saw the headline in the P-I, in June 2005—‘$11 Billion Monorail Plan.’ ” Public confidence collapsed, and so did Cogswell. “I called a friend, and we went to the bowling alley for a beer. I burst into tears, just kept sobbing and sobbing. I couldn’t stop.”

Rather than pausing to seek better financing, Mayor Greg Nickels pushed the monorail plan to another public vote—its fifth. This time, weary voters pulled the plug. “When it finally did crash, I walked around in tears for a week. My vision of what I was doing with my life, my future, my identity as a poet—they were all wrapped up in it. That’s when I gave up on Seattle. It was my muse. I haven’t written poetry since.”

Worse, Cogswell almost gave up on life itself. “I came super fucking close. That’s all I’m willing to say.” Five years later he’s still trying to sort out what happened. Sometimes he thinks Zioncheck’s cautionary example saved him from suicide: “If it weren’t for him I wouldn’t be alive,” he told me. Two weeks later he wasn’t so sure: “To have him as a warning helped me ride it out, but you don’t know until you go. Knowing about Zioncheck’s suicide didn’t help me avoid my own in the long run.… It was purely circumstance that saved me.”

BACK FROM THE BRINK

Cogswell threw himself into finishing Cthulhu. It premiered in 2007, found a few cultish fans, and otherwise bombed. “Lesson—don’t spend all your savings making a bad horror movie,” he says now. “Producing a movie is much harder than running for office.”

In 2008 Cogswell published a lurid account of its making for The Stranger: “I was the screenwriter, second-biggest investor, PR hack, extras coordinator, and a sometimes producer of the largest, most expensive locally produced film ever made in Seattle. It took five years. It cost $1 million, and its extremely slow projected return may have broken the bank for local distribution-quality films for the foreseeable future. It ruined my health, driving me to the brink of suicide twice, and from sobriety back down into a drinking life (and, briefly, the cocaine life below that ) and aggravating a chronic muscle condition that addicted me to painkillers…”

Updated September 22, 2010. This version corrects errors originally published in the October 2010 issue. Grant Cogswell, and not collaborator Cary Moon, crafted the message and the vision for the People’s Waterfront Coalition.

{page break}

And that was just the lead. It was a terrific behind-the-screen tell-all, a Northwest grunge gothic 8½. But not a good career move. Afterward Cogswell tried to get work running campaigns in Seattle, but everyone remembered the coke and pills and a blow job from a production assistant he’d mentioned in The Stranger. “I can’t get a job in the career I made in this town. People don’t trust me not to say crazy shit.”

Cogswell vows not to produce more films, but he still writes them, feverishly. Next stop for him and Gildark: Sevastopol, “a romantic comedy about Ukranian Internet brides.” A rock musical about John Keats. “A film about the illegitimate children of a doo-wop star, based on Aeschylus’s Oresteia.” And, of course, the last days of Marion Zioncheck. If they can get the money.

Cogswell went to LA seeking screenwriting work just as the economy busted. He wound up sharing a room in a flophouse and staying with the mother he hadn’t seen since he was four. Two years ago he hit bottom, “pushing the last of my saleable possessions—some books and camping gear—four miles in a shopping cart to sell them for $7.”

And then he bounced back—and conceived a new civic passion. Cogswell had first visited Mexico City in 2005, to get away from the monorail and Cthulhu madness. Last year he went to stay. He found he could live cheaply and find work, writing guidebooks and teaching English.

Sure enough, he got a big idea: Start what would be the only English-language bookstore in the world’s second-largest city and launch Mexico Review, a cross-cultural Paris Review for the coming Latin American Century. Seattle may have broken his heart, she didn’t steal it forever.

“What I was trying to create was already there in Mexico City,” exults Cogswell. He raves about its great transit, deep history, rich street life, and cosmopolitanism, how its 20 million people manage to get along in an area the size of metropolitan Seattle.

“I was hoping to see Seattle become a great and real city in my lifetime. But these things don’t happen in a single lifetime. They happen over centuries.”