Four Questions For…

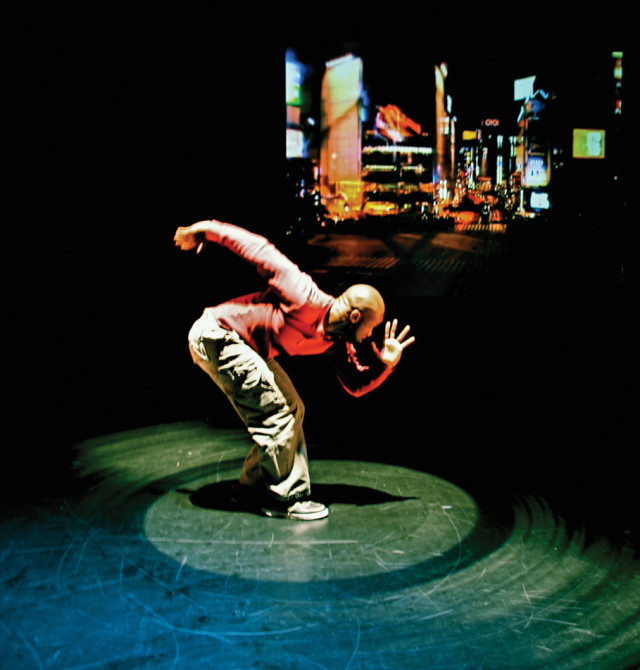

OAKLAND-BASED ARTIST Marc Bamuthi Joseph is both a Broadway veteran (the Tony-winning The Tap Dance Kid) and a National Poetry Slam champion. In The Break/s: A Mixtape for the Stage, his whirlwind talents for dance and spoken word power a piece that also features a DJ, a percussionist/beatboxer, video projections (including documentary footage and interviews), and the notion of hip-hop as “a new voice for a new politic.”

You’ve said, “I’m a poet, I’m an educator, and I move.” How do those things factor into this show? I begin with the idea that there are significant educational underpinnings and responsibilities that an artist can manifest. I found myself back in performance only after teaching high school and finding that the ways we assimilate information vary from person to person: Some folks are kinesthetic learners, some are auditory learners. I find ways of accessing different emotional and intellectual points for different audience members by engaging in different disciplines.

The show is the best elements of hip hop culture distilled in theatrical form. And when I say the best elements, I’m not talking about the misogyny or the mass consumerism that’s in a lot of corporate hip-hop—I’m talking about the ritual of community, the “yes, yes, y’all,” the reciprocity that makes hip-hop alive.

There’s a wry question in The Break/s: “What good is a black man in America if stripped of his threat?” Is the show an attempt to tell us the answer? I don’t think I’m telling you anything; I’m saying a lot but I’m not dictating anything. I wouldn’t say this is an attempt to expose an archetype. It’s more about American citizenship. It’s a travelogue—a travel diary across Planet Hip-Hop, that’s what I call it. The piece touches on four different continents and many different states. It takes place in Paris and in Japan and in Madison, Wisconsin and South Florida. There are personal stories, extrapolated stories. It’s much more about the children of the baby boomers and how we perceive and are perceived around the world through the prism of hip-hop culture.

Do you see what you’re doing as political—as a form of social action? Yes, I do. I am the artistic director of a nonprofit organization called Youth Speaks. Our mission statement is to engage the next generation of leaders by enabling them to discover, develop, publicly present, and apply voice. Part of what I’m doing aesthetically—because I come out of the poetry slam and hip-hop music and hip-hop culture—is kind of an evolutionary step. It’s in the same vein as Ntozake Shange and playwrights that have composed work in verse.

The work is political in the sense that I’m helping to push an art form that then, in turn, shapes where the young folks that I work with develop voice. There’s a Youth Speaks that’s based in Seattle. We also have an affiliate in Hawaii. And then we’re the hub of a national network program called Brave New Voices—so that work is overtly political and this work The Break/s is aesthetically political.

Why do you think hip-hop has become such a resonant language for so many people? Hip-hop is sexy. It’s a folkloric instrument. It’s of the body, right? You can’t escape what my folks in A Tribe Called Quest call The Low End Theory, what my Haitian folks would call the presence of Damballa, or what my scientific folks would call the reptilian brain at work. It’s a frequency that is at the core of hip-hop music and culture—even more than jazz music. So folks respond to that aspect of the music. And then the community aspect is what keeps the culture moving. There’s a way in to the music and to the culture if ou’re listening hard enough.