The Art of Politics

Image: 33RPM

The Fall Arts Season is primed to make us ponder where we’ve been, where we are, where we’re headed, and how far we have yet to go. Consider these 15 candidates worth your vote.

{page break}

Image: 33RPM

DANCE

Peace Movement

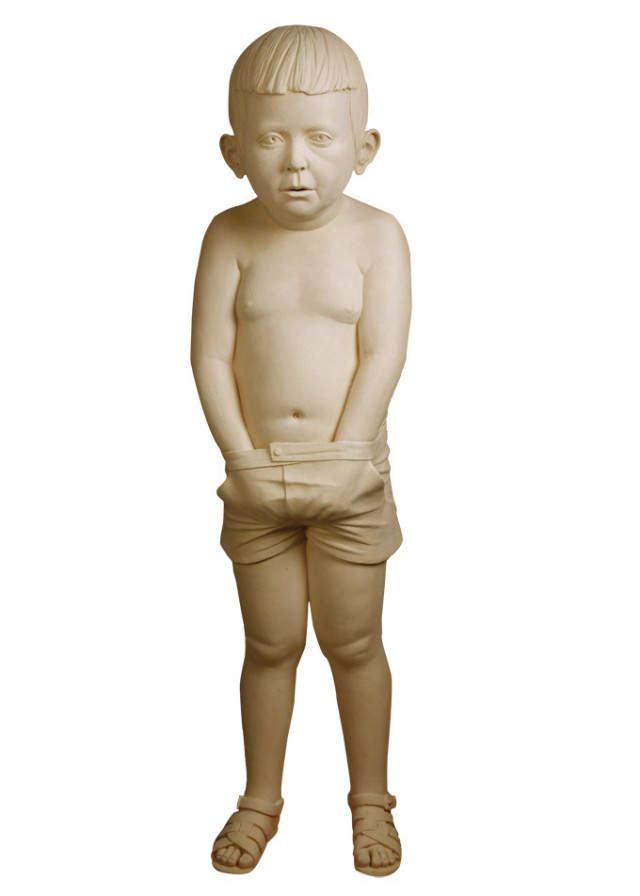

After Spectrum Dance Theater artistic director Donald Byrd finished his fellowship at Harvard’s Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue, he followed the lead of institute founding director Anna Deavere Smith. She’d galvanized audiences with one-woman shows like Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, about the aftermath of the Rodney King verdict, and spoke often of the possibility of solving some of the world’s problems using an artist’s methods. “So I thought it might be interesting,” Byrd decided, “if you put Palestinian, Israeli, and American artists together in a room and say, ‘Okay—make something.’”

Assembling A Chekhovian Resolution required Byrd to ignore the head of Tel Aviv’s major dance center who told Byrd he didn’t believe any Israeli choreographers would be interested. Byrd then pulled a choreographer couple, Nir Ben Gal and Liat Dror, out of semiretirement in the desert to work with Spectrum dancers. The possible participation of Dam, a young Palestinian rap group, initially made some at Spectrum wary until Nir Ben Gal told Byrd, “I love [Dam]—we listen to them all the time.”

And Byrd may still be awaiting word on whether another Palestinian musician, Simon Shaheen, will take part. So when the curtain finally rises…? “[Audiences] will consider that people regardless of their political, ideological, or cultural differences can figure out a way to work together,” says Byrd. “It may not be the ideal solution where everybody’s happy, but it’ll be a kind of Chekhovian resolution that at least provides some hope for the future.” www.themoore.com

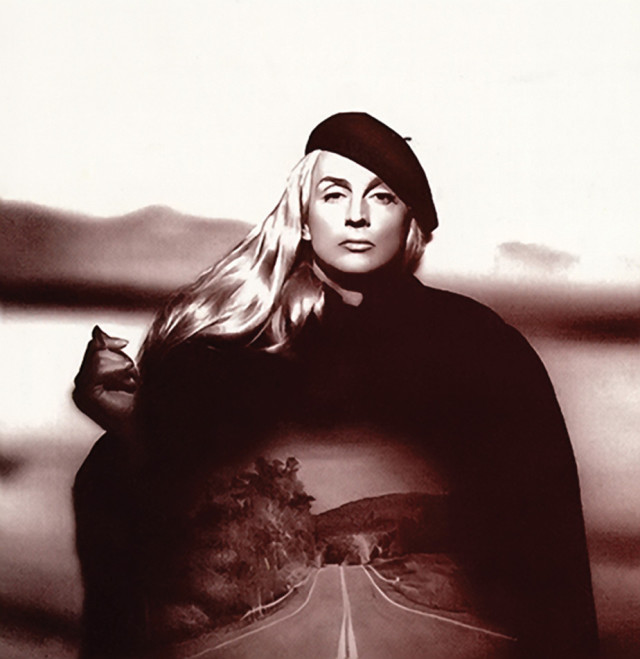

Image: Josef Astor

CONCERT

Both Sides—Now

All of John Kelly’s older sisters listened to Joni Mitchell records while he was growing up. “It was really the first time that I was exposed to soliloquy, wanderlust, and a certain kind of theatrical element in music,” he remembers. “For me, a kid from Jersey, it was, like, wow.” Kelly prefers not to define Paved Paradise: Redux, his live concert of Mitchell’s songs. “Initially, it was me wanting to do her music—period,” he explains, thinking back to his first gig in 1984. “And then the actor in me said, Okay, do I want to portray this character visually? And I said yes, because that’s the juicier challenge.”

It’s no drag show: It’s a total immersion. Kelly plaintively strums a dulcimer as his voice reaches the pure, poignant high of “O-oh, Caa-naa-DAAA!” on Mitchell’s “A Case of You.” He then somehow lowers into the later, smokier-voiced Joni. And he speaks in a dead-on duplication of her awkward, earnest stage patter. “But it’s not Beatlemania,” he warns. “You’re not going to get away that easy with this. It’s not about realness. It’s using all these elements to varying degrees for the purpose of warping expectations.” The refusal of a man in a dress to pin down exactly what we should make of him may be, in its singular way, the most political act of the season. At a time when society’s need for certainties runs rampant, Kelly’s magical incarnation says something beautiful about the unknowable, everyday fluidity of the self. www.tripledoor.com

{page break}

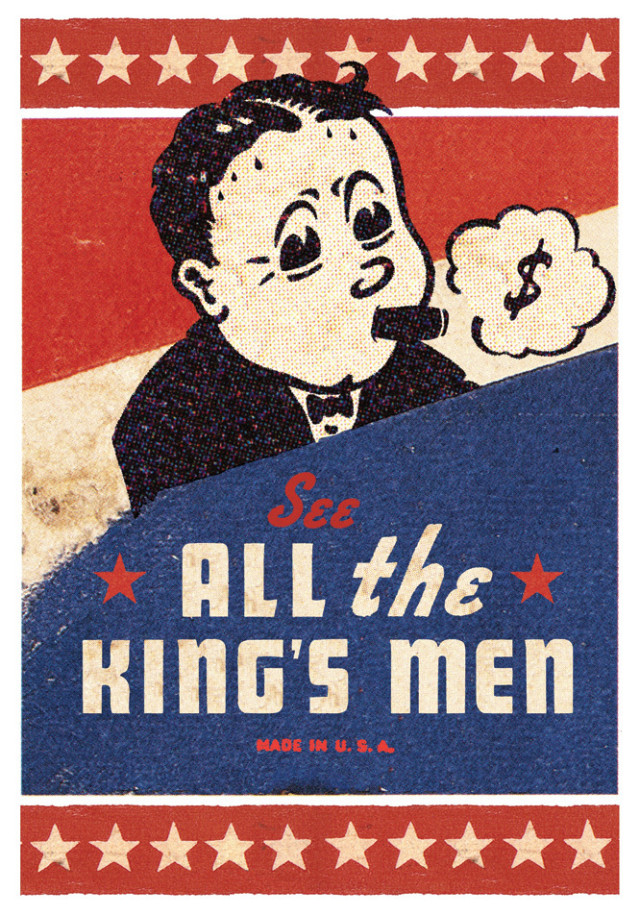

Image: Intiman Theater

THEATER

Royal Corruption

In 2004, Intiman Theatre began the American Cycle, five plays performed over five years that examine our country through our most potent stories. It’s fitting that the series ends in an election year with All the King’s Men, an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize–winning Robert Penn Warren novel that artistic director Bartlett Sher calls “a sort of shadow story of idealism in politics and how it intersects with the culture.” The plot presents the rise of Willie Stark, who sacrifices his ideals to gain the Louisiana state governorship in the 1930s, with the tragic disillusionment of his right-hand man, reporter Jack Burden. “The thing we don’t want to talk about when we tend to be idealists is that we can also be corrupted,” Sher muses. We should, he says, recognize theater’s transforming power: “The relationship between the arts and public and civic life in the United States is stronger maybe than ever. And I’m very positive about that.” www.intiman.org

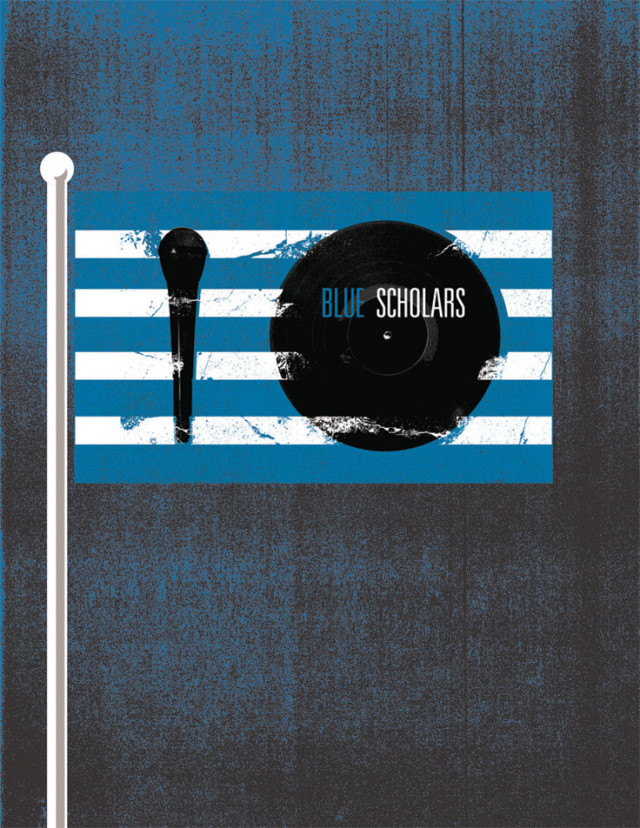

Image: 33RPM

CONCERT

Scholarly Sound

“There’s a lot of political music that doesn’t address people’s ills in a way that they can digest,” DJ Sabzi of Seattle’s breakout hip-hop group Blue Scholars told us back in May 2007. “We wanted to bring what’s happening in the world down to the level of human contact.” The two UW alums—one the son of Filipino immigrants, the other an Iranian American—met that goal, all right: MC Geologic, who handles the rhymes, and sonic master Sabzi are still touring on the strength of last year’s Bayani CD, still exploring a bracing new kind of inspirational music.

Their lyrics, like these from “Butter and Gun$ (Loyalty II),” send the tongue tripping over our national quagmire: Tell me whatever happened to askin’ a couple of questions? / They put us in competition to cause affliction with opposition. But, again, it’s that human connection, not untouchable worries like the presidential race, that remains foremost for Sabzi. “It’s at the grassroots level that the true work gets done,” he says. “I try to support my friends who are teachers, the people who are concretely trying to change the life of one or two people. I’ll vote, but most of our efforts are in strengthening our network of friends and neighbors.” If the past year and the Scholars’ rousing, righteous stage brio are any indication, that community will only increase. www.showboxonline.com

{page break}

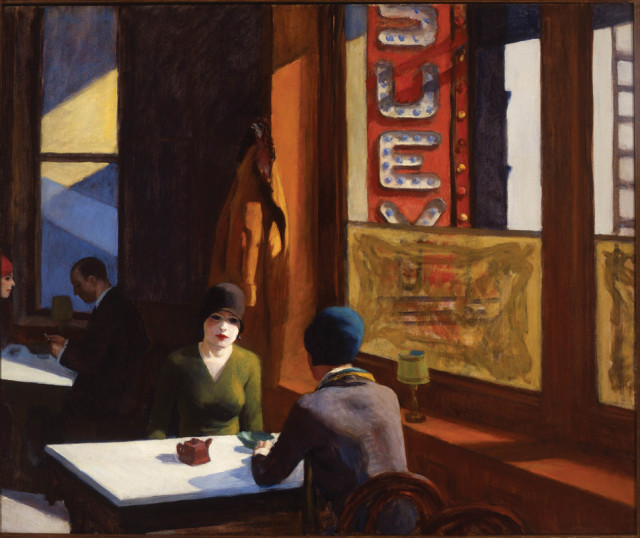

VISUAL ART

Image: Seattle Art Museum

Ladies First

When local collector Barney Ebsworth bequeathed the 1929 Edward Hopper masterwork Chop Suey to the Seattle Art Museum, Patti Junker saw that he’d also opened a window onto a different view of America in the early twentieth century. “There are no polemics about breadlines and battlefields and brutality,”

says Junker, who curated SAM’s Edward Hopper’s Women. “But somehow these [paintings] are more resonant of the human condition at a time of great deprivation and change.” Junker sought other Hopper women who suggested not the confident nation of purple mountain majesties but an increasingly unsure land of urban isolation.

The intimate exhibit features two works (Compartment C, Car 293 and Summer Evening) not seen publicly in at least a generation, as well as familiar ladies from his canvases who are rarely caught in person (e.g., the contemplative usher in the glow of New York Movie). “Hopper really appreciated this disconnection from contemporary society and from others,” Junker supposes. “I think he thought this was a portentous thing.” www.seattleartmuseum.org

THEATER

Reindeer Games

At a Christmas party one year, playwright Amy Boyce Holtcamp was watching the annual airing of Rudolph in his stop-motion tribulations and finally saw the TV special for what it really was: a metaphor for the ’60s. “Rudolph was being ostracized by the other reindeer for the color of his nose much as someone would be for the color of his skin. The does are all oppressed by Santa but, in a budding feminist maneuver, defy him and go off in search of their own. And the dentist elf is an obvious metaphor for homosexuality.”

Holtcamp’s Island of Misfits for Next Stage salutes the troubled reindeer and his friends with its own picaresque journey to the north. The main characters toil at an animated film company in 1969 until one of them, an African American puppeteer, gets his draft notice and decides to head to Canada. He’s joined by a filmographer who’s been donning mourning garb ever since JFK’s assassination. Realizing it’s not safe for a black man and white woman to travel together, they bring along the company’s gay white male accountant. “Can you ever truly divorce yourself from your country,” Holtcamp wonders, “even if your country considers you a misfit?” She’s betting the answer is a subversive holiday laugh. www.nextstage.org

Image: 33RPM

CLASSICAL

Igor and Elvis

A wartime soldier on leave trades his fiddle to the devil in exchange for enormous wealth that adds up to enormous emptiness. Igor Stravinsky’s 1918 septet The Soldier’s Tale is narrated for Northwest Sinfonietta by one actor and allows edgy, virtuosic parts for nearly every instrument: The trumpet pokes out to imply the not-so-sprightly side of marching music, the violin both mocks and rejoices, the percussion could be the drumroll that precedes either a magic trick or a firing squad. The piece addresses the malaise following the First World War but it resonates with anyone feeling the weight of the world today. “It’s one of the great masterpieces of the twentieth century and we’re doing a twentieth-century season, so it was a natural,” says Sinfonietta music director and conductor Christophe Chagnard. “The fact is that it’s true that the war is very heavy in people’s minds. And selling your soul to enrich yourself is not a new concept, obviously.”

Obviously. Composer Michael Daugherty’s 1993 Dead Elvis, which sounds like “Viva Las Vegas” twitching beneath classical conventions, also made the program. Daugherty wrote it for the same instruments as those in the The Soldier’s Tale—he sees the King’s deal with Colonel Parker as a similarly Faustian pact: “If you want to understand America and all its riddles,” he writes, “sooner or later you will have to deal with (Dead) Elvis.” www.nwsinfonietta.com

{page break}

VISUAL ART

The Body Politic

Image: Tom Holt

A little boy playing with himself in his shorts? “It’s a perverted studio over here,” jokes artist Tip Toland, whose life-size—and larger-than-life-size—sculptures in Melt, The Figure in Clay highlight the human form in all its imperfection. If we’re going to look at each other, the figures seem to demand, let’s really look—or, as Toland puts it, let’s begin “softening our hearts to what we’re afraid of.” She’d been sculpting bas-relief wall pieces ever since grad school in the 1980s, but the figures needed to stand on their own: “These kept talking to me. I wanted them to have more of a presence.”

Clay and sometimes human hair combine for an uncomfortably vivid authenticity. Surrealist touches heighten the effect; her five-year-old fumbling boy stands five feet tall. She hopes the piece inspires a humane tenderness instead of prurient fear. “The body that we’re all given is a gift,” she says, “but it’s not to be whitewashed and made to look nice.” Melt, The Figure in Clay, September 23–February 8, Bellevue Arts Museum, 425-519-0770; www.bellevuearts.org

DANCE

Last Look

When Eurydice is killed by a snake, the gods allow grief-stricken Orpheus to lead her from the underworld—on the condition that he never once look back at her. Well—he looked. And he never saw her again. Greek mythology reminds us of the fallibility of human action. “There’s so much in the myth about grief and how people treat each other and why people make the choices they make,” says Julie Tobiason, co–artistic director of Seattle Dance Project. “And we’re exploring those human emotions.”

In Project Orpheus six dancers work their way through classical, pop, and cabaret music chosen by three choreographers from disparate parts of Seattle’s dance world—Cornish instructor and longtime local impresario Wade Madsen, Pacific Northwest Ballet principal dancer Olivier Wevers, and Eastside dancemaker Eva Stone. “Wade is really interested in the scene where she gets bit by a snake,” Tobiason explains. “Olivier talked a lot about the emotional side of grief. Eva really connected with the underworld.” All found extra invigoration in the collaborative working environment. “I walked in one day and I thought, Gosh, this is such a great blend of different dance communities in Seattle,” says Tobiason. “It’s part of our vision to pull from different areas to create what we want to create.” www.seattledanceproject.org

{page break}

BOOKS

Memory Maker

Image: 33RPM

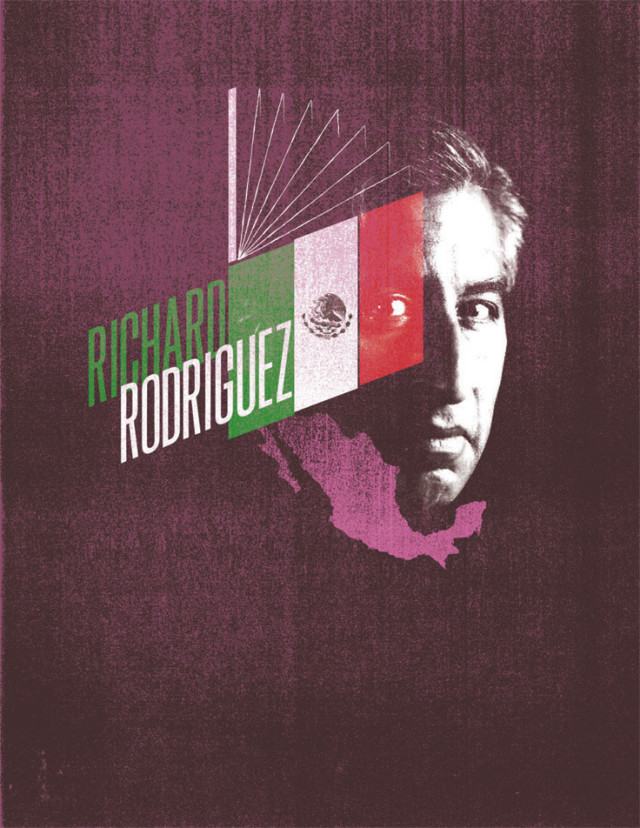

“I had cancer about four years ago,” says writer Richard Rodriguez. “I’m really interested in the whole process of injury and the wound and one’s association with other sick people. I went through, as most gay men did, the process of helping a lot of men die in the 1980s and ’90s. But I never thought, because I had the survivor’s sense of being spared, that I would be struck down quite so soon after the death of a very good friend. And it’s really that: learning that you belong to the nation of the wounded.”

The chance to hear that lesson is the main reason to grab a seat at November’s edition of the Hugo Literary Series, where Rodriguez and two other writers—Allen Johnson and Sallie Tisdale—each read a new work based on a personal-injury theme. Beginning with his lyrical Hunger of Memory in 1982, which contained a disavowal of bilingual education that enraged liberals and fellow Latino Americans, Rodriguez has championed through memoir the notion that people cannot be defined through easy ethnic or political associations. “I treasure, at this later stage in my life, my own contradictions,” he agrees. “I’m no longer seeking a straight line—in my own life or in my writing. I like the fact that I live within a certain kind of complexity.” www.hugohouse.org

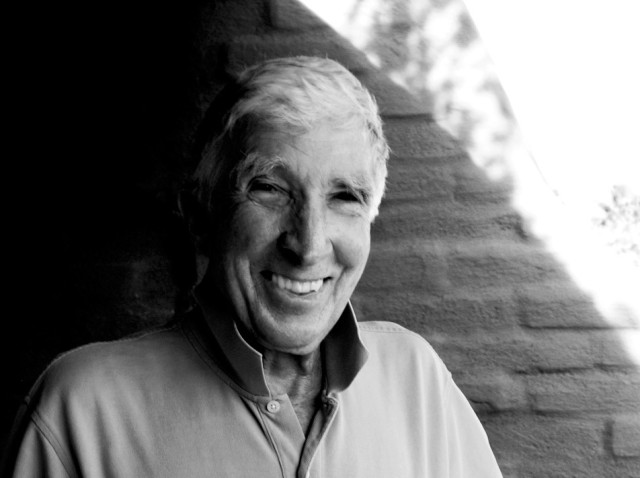

Book Report

Image: Martha Updike

John Updike’s province, as Seattle Arts and Lectures reminds us, is “the American small town and the Protestant middle class,” and he won two Pulitzers for novels about hero Rabbit Angstrom in just that territory. But Updike’s land has proven far larger. For years his frank essays in The New Yorker have been a reason to reconsider national identity through revered American literature. L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz pales next to the unfaithful movie classic, Updike notes, because Baum “did not grasp that [his tale] concerns our ability to survive disillusion.” And it’s not the “n” word we should worry about in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; it’s the novel’s second half, in which “it’s as if Twain forgot what slavery is—the constriction of it, the helplessness of it, all suspended while Tom Sawyer toys with a tediously extended, bookish prank.” Updike’s visit should push us out of our cloistered complacency and into the fresh, open field of a good argument. www.lectures.org

{page break}

THEATER

One Man, One Nation

Image: Daniel Beaty

For his latest work, playwright and performer Daniel Beaty drew on the National Urban League’s report The State of Black America 2007: Portrait of the Black Male. Resurrection re-creates one night in the lives of six black men—from a child genius to an elderly bishop. Their economic, relationship, and physical challenges may be based on issues in the report, but what happens to these men on this particular night, says Beaty, “is the revelation of the play,” and you’ll have to buy a ticket to watch the details unravel. He calls Resurrection a “contemporary male response” to the ’70s hit For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf, a collage of theatrical poems about the struggles of African American women. “They’re all connected to each other,” he says of the men in his piece. “They’re all living in the same time period, in the same community. You meet these six individuals and you gradually get to know them in a very intimate way.”

Beaty, an Obie winner for his Emergence-See!, blends music, poetry, and comedy. “I believe we don’t discuss a lot of important issues because they seem unbearable,” he says. “The humor and the quirkiness enable a new kind of conversation to happen.” It’s a conversation that also enables Beaty to perform solo: Though the piece can be performed by an ensemble, he’ll be everywhere—and everyone—at once for the full 75 minutes. www.cdforum.org

Dinner Debate

Image: Rick Burkhart

All of Rick Burkhardt’s degrees were in music. Andy Gricevich majored in contemporary poetry. They met Ryan Higgins, a theater grad, while they were all at UC San Diego. In 2005 they formed the Nonsense Company to pool their disparate talents. In the Great Hymn of Thanksgiving/Conversation Storm, the three friends deliver an absurdist musical about what Burkhardt calls “what it’s been like to live in America during the Iraq war, and having to live through these discussions of whether or not we want to be torturing people.” Thanksgiving uses silverware as instruments and a rhythmic table talk that’s a “kind of fractured sound of what you might be hearing from the television.” Conversation finds each of the troupe’s members reaching to surreal lengths in the attempt to win an unreasonable argument. “Although in my mind,” Burkhardt teases, “it doesn’t become any more surreal than our national conversation has been in the last six or seven years.” www.infinitelaughs.com

{page break}

DANCE

Vanishing Point

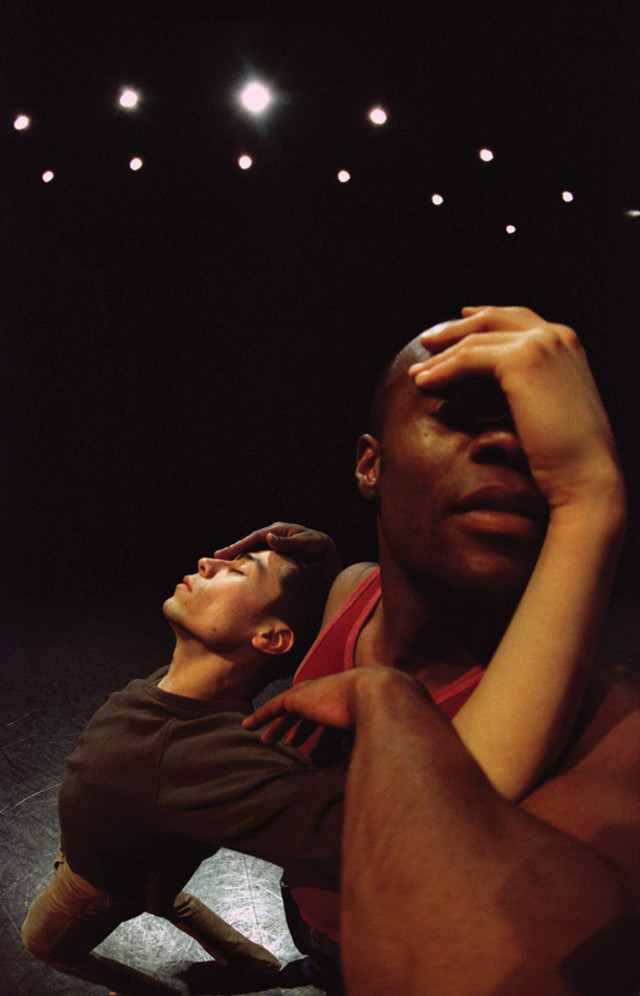

Image: Chris Randle

Vancouver choreographer Crystal Pite was in Montreal for Canada’s Remembrance Day in 2005. “The whole country stops and we do a minute of silence and everybody wears poppies for about a month,” Pite says. “I had a poppy on my backpack and an American guy asked me what all the poppies were about. I started thinking about our veterans from the First and Second World Wars and how they’re just vanishing—and, with them, their stories and their memories.” Pite transferred that sentiment into Lost Action, feeling too overwhelmed to deal with the subject of veterans and choosing instead to address the ever-evaporating nature of dance itself. “Because the thing is always in a state of disappearing,” she offers, “I think it’s a really great metaphor for death and life and the present moment.”

Owen Belton, her longtime collaborator, taped acoustic instruments and sampled sounds; there’s also recorded dialogue of four men talking about an ambiguously violent situation. Pite and the other six members of her troupe Kidd Pivot perform intensely physical images of conflict and rescue. She hadn’t wanted to make a piece about soldiers but, six weeks later, she looked back “and realized that I’d gone ahead and done it anyway.” Lost Action, November 20–22, On the Boards, 206-217-9888; www.ontheboards.org

CLASSICAL

Facing the Music

If you look at the typical American orchestra you’re not seeing many African Americans or Latinos; the nonprofit, classical music Sphinx Organization reports that those two minorities combined account for less than 5 percent of professional orchestra musicians. Violinists Ilmar Gavilan and Melissa White, violist Juan-Miguel Hernandez, and cellist Desmond Neysmith set out to literally change the face of classical music as the Harlem Quartet.

Each member of this black and Latin American chamber ensemble playing for the UW World Series achieved first-place laureates at the Sphinx Competition. Their stated mission is “to advance diversity in classical music,” and watching them in action you can see that dream coming true: A hushed, exquisite rendering of the Ravel Quartet in F Major feels as fresh, young, and persuasive as the locomotive that is Wynton Marsalis’s “Hellbound Highball.” Take the A Train, their debut CD, features a lot of Marsalis compositions and the titular standard. It’s a first-class ticket, but nothing compared to the pleasure of hearing them live. Harlem Quartet, December 9, Meany Hall, 206-543-4880; www.uwworldseries.org