Vision Zero or Zero Vision?

Image: Allison Vu

The cyclists hold their bikes like shields in the middle of the road. On a sweltering midsummer night, dozens have slowly pedaled down the West Seattle Bridge Trail along Southwest Spokane Street. One by one, two by two, they’re more procession than peloton. Near 11th, when the coast is clear, a few turn left into the thoroughfare and dismount. Standing behind their wheels and holding up traffic, they allow their fellow riders to cross behind them without incident. No one could possibly take these human stop signs for granted. Two weeks earlier, on this patch of Harbor Island pavement, a sedan driver struck and killed cyclist Robb Mason.

The memorial ride hosted by Critical Mass Seattle on that July evening drew an outpouring of grief from the city’s cycling community and those who knew the skillful massage therapist. Under golden-hour light, they laid flowers in the crosswalk and huddled beneath a white “ghost bike” affixed impressively high on a light pole.

But a certain thinly veiled anger also attended the gathering. There was the immediate outrage: The driver had sped off after striking Mason and, as of press time, had yet to be caught or come forward. And then there was the longer-running indignation that nags anyone trying to navigate this city, be it by bike, car, wheelchair, or foot: The streets, as presently designed, aren’t remotely safe enough.

Mason’s death marked the 14th traffic fatality of the year in Seattle. The very same city that, a full seven years ago, adopted a plan to end deaths and serious injuries on its roads by 2030.

Halfway to the target date of “Vision Zero” and that goal has never seemed further from reach. Last year was Seattle’s deadliest, traffic-wise, since 2006. Even as many workers ditched commutes for couches during the pandemic, major crashes remained jarringly common. “We’re seeing trends headed in the wrong direction,” says Allison Schwartz, Vision Zero coordinator for the Seattle Department of Transportation.

Pedestrian deaths have risen significantly since the debut of the plan, and in 2021, they peaked, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the city’s total traffic deaths. About 27 percent of the fatalities were unhoused people. Transit wonks were blindsided. They expected fatalities to drop when office workers went remote, Schwartz says. But it turns out all those empty roads did was speed vehicles up. The lack of car congestion likely led to more lethal collisions.

At the outset of 2022, a string of cyclist deaths heightened concerns too. Claudia Mason couldn’t believe her husband was one of those victims. Cradling a framed photo of Robb and flowers someone handed her, she told the memorial riders that the 63-year-old was “hyper-aware of his surroundings.” This was a man so attuned to his senses, he told Claudia one night during massage therapy training he could feel his fingertips changing.

Instead of driving, Robb and Claudia Mason often walked and cycled around the city together.

Image: courtesy Claudia Mason

A few years before the crash, he’d started commuting by scooter and bike from their Magnolia home to West Seattle, where his hands worked magic on massage clients. He took his new rides on the bus, on the water taxi. “He tried every which way to get here by not driving.” To adopt the greener modes of transit the city’s progressive types champion every chance they can get.

But in a city long designed for the fast, uninterrupted movement of motor vehicles, that lifestyle eventually placed him in harm’s way. A byzantine transit corridor, where industrial traffic lanes, railroad tracks, and a bike trail intersect chaotically, exposed him to the car that killed him after work one night. He died, his wife would later say, in the street.

Standing before the group near the scene of the crime, Claudia let the roar of vehicles behind her pass before she spoke. An avid cyclist herself, she didn’t know that the bike path here reversed direction just beyond the West Seattle Low Bridge, allowing riders to cross beneath the span without entering the street. Maybe Robb didn’t either.

She pushed her personal suffering down for a moment to express a broader frustration, one that will certainly be echoed during another memorial ride for Robb tomorrow. “This area,” she said, “needs to be changed.”

In 2019, Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan tried to slow traffic by lowering speed limits to 25 miles per hour on many Seattle streets.

But the new signs along those arterials can only help so much. When thoroughfares still look the same, even conscientious drivers might zoom down them as if nothing has changed. Southwest Spokane Street, the yawning road where a car hit Robb Mason’s body so violently he died of blunt force injuries before an ambulance could whisk him away, is supposed to top out at 25 miles per hour.

Transit activists now call these collisions “crashes,” not “accidents.” They’re tragedies born not from bad luck but the inevitabilities of poor infrastructure, the thinking goes.

Even in an urbanist’s utopia, there has to be some room for human error. Vision Zero acknowledges mistakes will happen.

A ghost bike remains near the spot where a hit-and-run driver killed Robb Mason.

So Allison Schwartz understands the skepticism that the city can ever eliminate collisions resulting in serious injuries or deaths. Yet she won’t surrender the cause. She points to Oslo, the Nordic city that has seen a drastic reduction in (but not zero, technically) serious collisions since moving to create a car-free downtown.

Seattle isn’t excommunicating Subarus from the city’s core anytime soon. Schwartz instead backs smaller changes that can at least help us reverse our current trajectory of traffic deaths. Reducing vehicle lanes. Adding more leading pedestrian intervals, which give walkers a three-second head start before the signal turns. Focusing on traffic danger zones, namely Aurora Avenue North; thoroughfares in Southeast Seattle such as Martin Luther King Jr. Way South and Rainier Avenue South; and basically all of SoDo.

Reginald “Doc” Wilson, the founder of a nonprofit that, as part of its mission, organizes rides to Black-led businesses and institutions, regularly cycles down Rainier. “It’s deadly,” the Peace Peloton executive director says, noting he’s been pushed up on the curb and even had ice thrown on him while riding next to cars.

But Wilson also knows that bikers aren’t always the chillest, either. “There are some cyclists out there who are total assholes.” And even more cyclists, including Wilson, also get behind the wheel of cars on occasion.

Given this necessary coexistence, he’d like to see more transit advocates lead with empathy rather than bias. It might seem like common sense to a young, able-bodied person to ban cars from Lake Washington Boulevard, but how would that affect older residents who can’t get around otherwise?

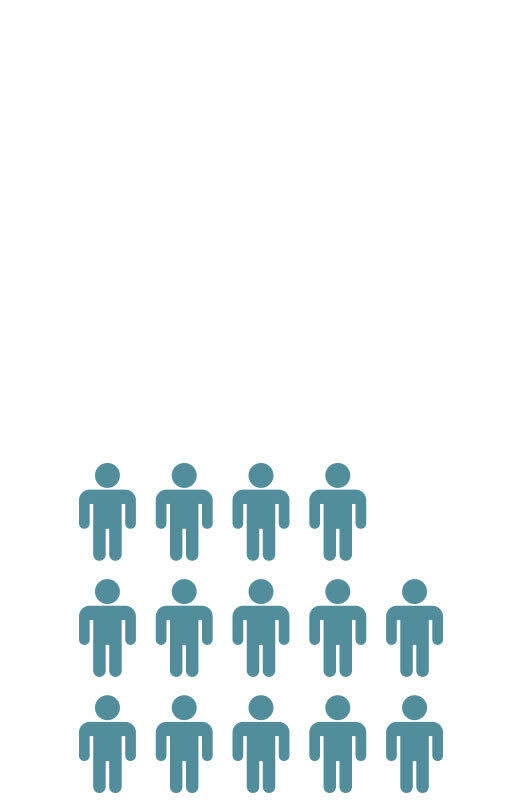

Traffic Fatalities in Seattle

2017

(24)

2018

(14)

2019

(26)

2020

(25)

2021

(30)

Navigating this tangle of perspectives will be dizzying for new SDOT director Greg Spotts. During a presser this summer, the former Los Angeles transit official said he’ll conduct a “top to bottom” review of Vision Zero and adjust accordingly. Gordon Padelford, the executive director of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, is “cautiously optimistic” about the new administration’s approach to addressing traffic deaths. “They’re saying the right things.”

Critical Mass Seattle member Joe Hand doesn’t agree. Ambitious as it may be, Vision Zero’s 2030 timeline is “a slap in the face” to the rider. “We shouldn’t be accepting any deaths.”

About 20 cyclists relay this message across the street from Seattle City Hall on a foggy August morning. As city council’s transportation committee prepares to convene inside, Critical Mass riders urge drivers to “Honk 4 Our Safety” along a curb on Fourth Avenue.

Many oblige. A truck driver lays on the horn for a block and a half. Others quickly scan signs the group has stapled to a boarded fence. Some of them list the names of recent traffic fatalities. Near the middle, in big purple letters, is “Robb J. Mason.”

Claudia Mason wasn’t there to see it. Though she somehow mustered a rousing speech at the group’s memorial ride, Robb’s death had flattened her. She went to Trader Joe’s and saw how few things she needed to buy for just herself. She broke down in the checkout line.

Eventually, though, she’d return to work at Elliott Bay Book Company, even cycling there from Magnolia. Some of her colleagues attended the funeral. Many were in disbelief. “It’s just not a normal death,” Claudia says.

Not normal. But in this city, still far from nonexistent.