Why Doesn't the City Already Have a Public Bank?

State senator Bob Hasegawa announces his mayoral campaign outside the downtown Wells Fargo Center on May 9, 2017.

Image: Hayat Norimine

When state senator Bob Hasegawa officially became a candidate for mayor Tuesday, he quickly made a city-owned bank central to his platform—announcing his run in front of the downtown Wells Fargo Center in an anti-corporate message consistent with his sponsored bills in the legislature throughout the years.

Hasegawa, a former union leader and Bernie Sanders delegate, said he wants to set up a task force to come up with recommendations for a public bank, insisting it's the only way to ensure the city can keep a clean social conscience. The City Council's decision to boycott Wells Fargo back in February was a good start, he said, but there will never be great alternatives. In the legislature he's pushed for a state-owned bank, with North Dakota (the only one in the country, established nearly 100 years ago) as a model.

"I think we just have to do it. If we keep tiptoeing around the edges, it's a gridlock recipe of never happening," Hasegawa said to PubliCola on Tuesday. "The lawsuits are going to come regardless because the banks aren't going to tolerate it. Let's just do it see what happens."

It's far from the first time a municipal bank has been considered. Two years ago, then-council member Nick Licata consulted with Hugh Spitzer—UW law professor and a go-to state constitutional expert who worked for the city years ago—and city attorney Pete Holmes, who created a memo outlining the risks.

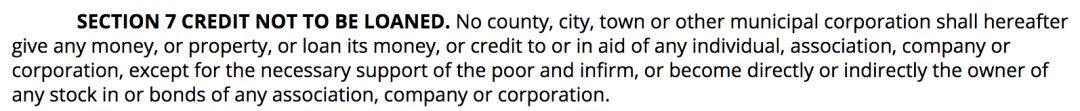

Spitzer said to PubliCola on Tuesday that two sections of the state constitution pose a challenge: Article eight, Sections five and seven.

"So the proposals that are most likely to succeed are those which provide loans to low-income people," Spitzer said. "The problem is that the state auditor watches over cities and will blow the whistle if they conclude that there's some kind of an unconstitutional loan. That’s kind of the big picture issue that you have to deal with."

That's just dealing with the state constitution, but there are challenges with the local government's authority as well, Spitzer said: "Cities have limited authority to make loans to individuals or businesses."

Seattle would have to determine that the investments they're making are prudent and legal. Cities and states are limited to investing only in certain federal securities, bonds, and notes. If loans are considered investments, cities would have a difficult time lending to individuals or businesses.

Here's what Licata said in an email to PubliCola about why he ultimately chose to drop it:

"Basically did not have enough time to mount a major campaign to push for a municipal public bank. [It] would have taken a larger more organized community effort than what existed. The legal problems might have been able to be worked around, but it would most certainly have been challenged, and money or expert pro-bono lawyer work would have been needed."

Council member Lisa Herbold, who worked as a legislative aide for Licata, said she would "definitely like to see it happen" but thinks there are a lot of prerequisite steps before the city can pursue a public bank—like changing state law.

"To me it's not a comparable case to [the city income tax] where there's a question about the legal authority," Herbold said to PubliCola. "I think there are some very specific things we need to do in state law before pursuing a municipal bank, and those things haven't occurred yet. It's not like this is something we can go on our own without that authority."

Ironically, Hasegawa said he grew frustrated with how little he could change as a state legislator, one of his reasons for becoming a mayoral candidate.

"As a mayor, I think that there would be a lot more public authority to take a serious look at this," Hasegawa said.

Updated May 11, 2017, at 8:42am. This post contains screenshots and a more thorough quote from Lisa Herbold.