Will the Upzone Upend the University District?

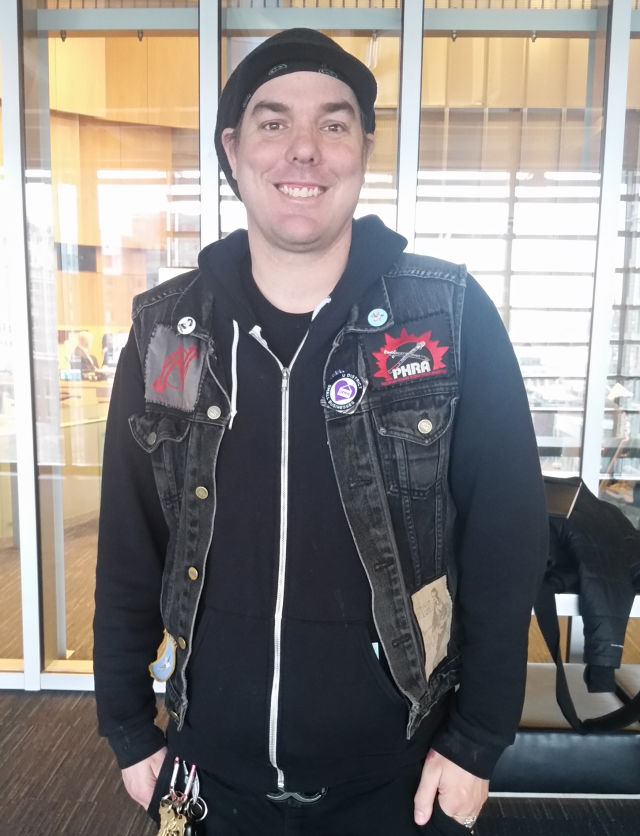

Shilo Murphy, executive director of the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance.

He’s said it before and he’ll say it again: Shilo Murphy will be an “Ave Rat” until the day he dies.

Murphy, executive director of the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance (PHRA), was homeless on the streets of the University District in the 1990s. When he talks about the neighborhood, his fondness for it is palpable. He recalls the bonds he formed with small business owners who looked out for him on the daily: a 75-cent discount off falafel when his funds didn’t quite add up, a free meal now and then, places he could always return to and depend on. To this day, Murphy buys his wife’s birthday present each year from Gargoyles Statuary.

Those relationships were a vital part of his safety net—perhaps the most important part. He says it was the University District’s small businesses that were there for him, more so than any city program. Given that business owners tend to earn the NIMBY badge in debates on homelessness policy (hate or love the ever-present acronym), that kind of connection between the homeless population and business is a rarity to be cherished.

That is the piece of the neighborhood’s character that Murphy is afraid of losing if the University District upzone, approved Tuesday morning by Seattle City Council’s land-use committee leads to rising rents and displacement, as some fear (the ordinance will likely move to a full council vote later this month).

Murphy also believes the swath of social services in the area, including PHRA’s needle exchange and ROOTS Young Adult Shelter, may be threatened.

Plans for the upzone have been in the works for years in anticipation of a new Sound Transit light rail station, slated to open in 2021. Response from the community has been wide ranging, from those who believe it won’t lead to growth fast enough to those like John Fox of the Seattle Displacement Coalition, who called it a “blueprint for gentrification and displacement,” on Tuesday.

Business owners who attended the meeting said they were encouraged by changes the council adopted in response to community feedback, praising the decision to hold off on upzoning University Way Northeast (“the Ave”), as well as to reduce maximum building and storefront width in key areas, among others.

“We’re making progress. Small businesses are being heard,” says Rick McLaughlin, owner of Big Time Brewery. “If the city continues to work with us, I think this will be great for Seattle. Whatever they get away with here will happen in other neighborhoods, so it’s not just about the University District.”

McLaughlin says he is pro-growth, but wants more time to conduct a study to look at how the changes will affect businesses, and hopes to add as many amendments as possible to make sure the area stays affordable. He supports a proposal by city council member Lisa Herbold to preserve legacy businesses and her resolution requesting an evaluation of residential displacement.

Murphy is only mildly assuaged by the council’s amendment to pause the upzone on the Ave.

“I’m hopeful, but it’s temporary.” Murphy says. He doesn’t see services like the needle exchange, which operates out of the University Temple United Methodist Church, surviving a rezone. His concern? If the building gets redeveloped, it would be damn near impossible to find another affordable space if offices go up and tech startups move in.

“In this rezone, places like the needle exchange will go away,” Murphy says. “And in the middle of a heroin epidemic, we will not have these services.”

Staff in council member Lisa Herbold’s office pointed to language in the upzone ordinance that provides some incentive to include human services in new developments. Herbold’s displacement ordinance also affirms the city’s intent to “review future legislative rezones to determine if they pose a risk of increasing the displacement of residents, especially marginalized populations, and the businesses and institutions that serve them.”

At this point in the process, it’s hard for anyone to get a clear vision of what the future will look like. But Murphy believes that the loss of any longstanding business would also be a loss for the homeless community.

“The Ave is a bunch of mom-and-pop shops that sometimes barely make ends meet, and have always supported those in the neighborhood even when it wasn’t in their interest,” he says. “What happens to one business affects the entire homeless population.”

If the area’s fate is another South Lake Union—a gleaming possibility for some, an ultimate fear for others—it becomes significantly harder for Murphy to envision creating the kinds of relationships he believes make the University District special.