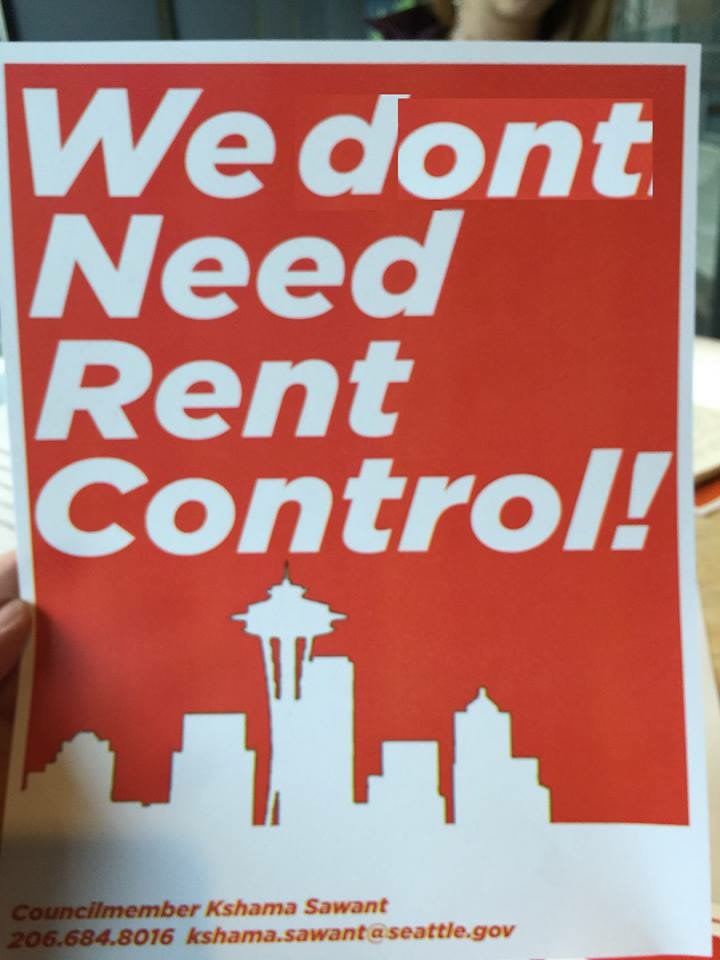

We Don't Need Rent Control

The latest panacea being touted to solve rising housing prices is rent control. But what’s the real story about rent control and housing priced here in Seattle? First, rent control won’t work to achieve its stated purpose, lowering overall housing prices. There isn’t any doubt that lowering prices for some units by fiat will keep those prices frozen, but economists have achieved unusual consensus that rent control causes more problems than it solves, including higher overall housing prices.

Passing a resolution addressed to Olympia won’t create a single affordable apartment for people struggling to pay their rent.

Sure the city council could have a tantrum about the fact that they are preempted by state law from enacting rent control, but passing a fist-shaking resolution addressed to Olympia won’t create a single affordable apartment for people struggling to pay their rent.

The truth is we don’t need rent control because we already have price controls in place for many units in the city. Based on the Puget Sound Regional Council’s database on affordable housing, Seattle has about 82,000 rental units that are priced affordably—with rents that are 30 percent of monthly area median income (AMI)—for people who earn zero to 80 percent of AMI. That’s the income band targeted by the mayor’s call for 20,000 new affordable housing units in the next 10 years. (Eighty percent of AMI for a single person is $44,750; that band should pay about $1,198 in rent. Fifty percent of AMI for a single person is $39,000; renters in that band should be paying about $827.) Of those 82,000 existing units, there are already 36,000 that are rent restricted, meaning the rents of those units are locked in—controlled if you like—for anywhere from 12 to 40 years.

Those 36,000 units, roughly 44 percent of all the units at those levels of income are set by government agencies and covenants; they are a mix of units paid for by government grant, the city’s housing levy, through the city’s Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program, or vouchers issued by the Seattle Housing Authority. The rents won’t go up unless those units go though an extensive process or are converted into market rate units. That happens, but the city has a lot of control over that even though the Office of Housing only tracks a fraction of these units to be sure they aren’t in financial trouble or has an owner that is having trouble operating them.

Today, the city could start tracking every single one of these rent-restricted units, determine how long their rent restrictions are in effect, and develop backstops to be sure they stay rent controlled. Additionally, the council could adopt a strong resolution directing staff to develop a workable plan to use the city’s borrowing (bonding) authority to build housing on usable pieces of public land and to buy rent-restricted buildings that are in trouble. The council could push to expand the Seattle housing levy, the MFTE program that uses reduced property taxes to stabilize rents, and expand SHA’s voucher program. And they should stop wasting time worrying about rent control.

If you want to penalize builders and landlords then these solution may not make you happy. But if you want to solve the problem, all of these programs work successfully already to restrict rent increases in thousands of units all over the city today and can be improved to make more affordable housing now, not in some distant, fantastical worker’s paradise.

Roger Valdez is the head of Smart Growth Seattle, a developer-backed advocacy group.

In March, advocates from low-income advocacy group Puget Sound Sage made the case for a linkage fee on developers to help produce affordable housing.