Union Preschool Measure Will Cost $3 Million...or $100 Million

In November, Seattle voters will choose between two measures relating to early childcare and education. One, city-backed Prop 1 B to fund preschool slots (with an eventual goal of establishing universal preschool) will cost $58 million over four years. The other, Prop 1 A, backed by early childcare and education unions, will cost $3 million per year.

Or $100 million. Or something in between.

Prop 1A could cost a couple million per year, or a hundred; it all depends on whether a court rules certain parts of the measure as ‘aspirational’ or ‘mandatory.’

How can there be so much disagreement over the cost of Proposition 1A? Simply put: no one knows how much it will cost, because no one knows how its legal implications will play out in court. It could cost a couple million per year, or a hundred; it all depends on whether a court rules certain parts of the measure as ‘aspirational’ or ‘mandatory.’

Prop 1A, backed by education and early childcare workers’ unions AFT Washington and SEIU Local 925, will run on November’s ballot in opposition to Prop 1B, thanks to the city council’s decision (subsequently upheld in court) that the two proposals are in conflict. Prop 1B would launch a pilot-version of universal preschool for Seattle three and four year olds, serving up to 2,000 children over 4 years at a cost of $58 million to city taxpayers.

Prop 1A would: speed-up the minimum wage increase (passed earlier this year) for early childhood workers; ban violent felons from the industry; and expand training requirements for early childhood workers as well as union influence on that training. No funding source is included in the measure.

Less concretely, the measure might also guarantee Seattleites the right to affordable early childhood education—or, depending on whom you ask, it might just say that affordable early childhood education is a laudable goal that the city ought to pursue in a general and non-obligatory way. This is the crux of the dispute over Prop 1A's cost, so the text (here's the whole thing, with comments from its advocates) is worth a long quotation (emphasis added):

Sec. 301.

A. It shall be the policy of the City of Seattle that early childhood education should be affordable and that no family should have to pay more than ten percent (10%) of gross family income on early education and child care. This policy is intended to increase affordability of child care in conformance with federal and expert recommendations on affordability.

B. The City shall, within twelve months of the effective date of this Ordinance, adopt goals, timelines, and milestones for implementing this affordability standard. In adopting these standards, the City shall consult with stakeholders, who at a minimum must include parents, communities of color, child advocates, low income advocates, and the provider organization.

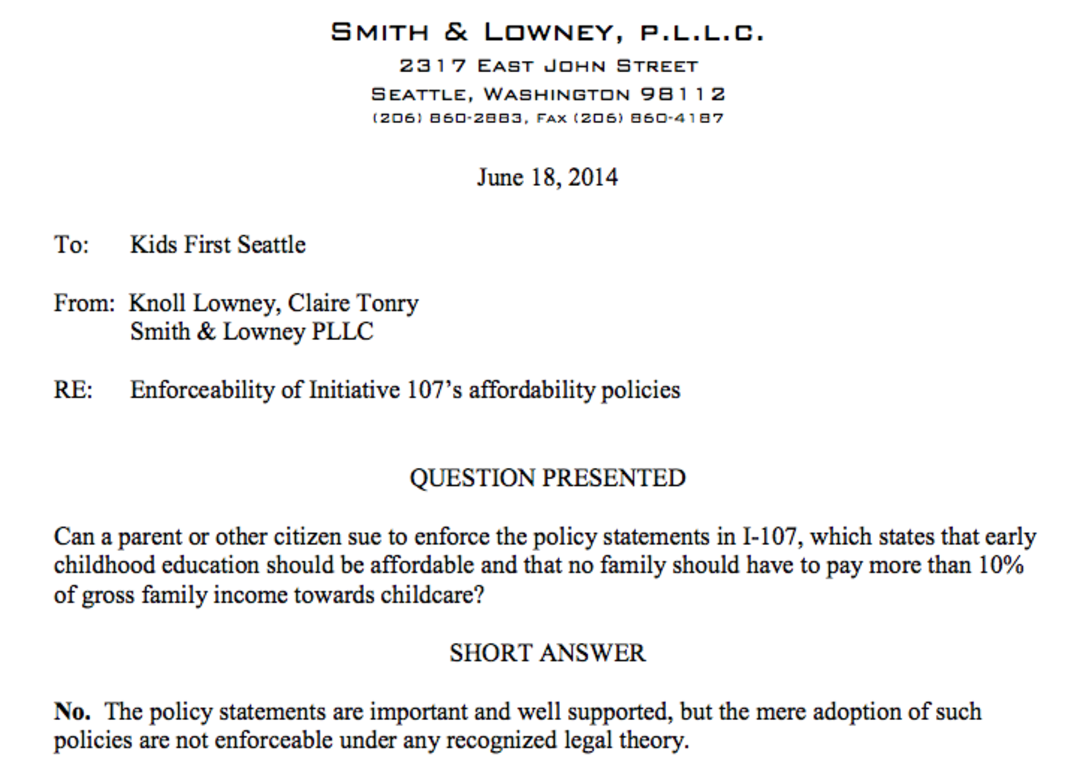

The operative words here, according to a legal memo released by advocates of Prop 1A, are “should” and “shall.” The Smith and Lowney memo argues that the language in Sec. 301 A is “precatory,” which is a Scrabble-word for 'aspirational' or 'wishful.' On this reading, Sec. 301 A amounts to “it shall be the policy of the City of Seattle that it would be nice if early childhood education were affordable.” Smith and Lowney argue that since this language does not create a “clear duty to act,” there is no way for courts to force the city to actually make childcare affordable—and hence no definite price tag attached to the affordability clause.

Smith & Lowney memo arguing for a soft interpretation of Prop 1A.

You may be asking yourself then, 'So why is the language there at all, if it's unenforcible?'

The cynical answer is that it's a Trojan Horse the unions are plotting to exploit in the future: AFT and SEIU 925 might be trying to sneak a wolf of a mandate past voters in the sheep's clothing of "precatory" language. A more benign interpretation is that Prop 1A would set a precedent—not something a court could enforce, but an official policy goal that would give the unions the high-ground in future debates over early childcare funding.

Sandeep Kaushik, political consultant and spokesperson for Prop 1B, isn’t convinced by Smith and Lowney's arguments. (Kaushik co-founded PubliCola back in 2008, but hasn't been involved in PubliCola for several years.) “Not only is [Prop 1A] unfunded, but it creates this huge unfunded mandate,” he says, pointing to another section of the measure which explicitly includes the right to sue the city for non-compliance (emphasis added):

Sec. 702

The requirements contained in this act constitute ministerial, mandatory, and nondiscretionary duties, the performance of which can be judicially compelled in an action brought by any party with standing. Should a person be required to bring suit to enforce this ordinance, and the City is found to be in violation, the City shall be responsible for reimbursement of the costs of such enforcement action, including reasonable attorneys’ fees and costs.

The big question, of course, is whether Sec. 301’s language about how early childhood education “should” be affordable is subject to Sec. 702’s provision for court-ordered compliance. Are Sec. 301’s goals aspirational, or mandatory?

Here’s why this matters: if they’re aspirational, then the pro-Prop 1A camp’s analysis of the measure’s cost—about $3 or $4 million per year—is probably closer to the truth. If the goals turn out to really be mandates, however, the City Budget Office’s estimate—something like $100 million per year—is the better number to rely on.

But remember: all of this assumes a strong interpretation of Prop 1A’s goals—that everything which might cost the city money will cost the city money.

When I asked the Budget Office how they reached that number, they said that they assumed a strong interpretation of the measure’s goals and then used Census data to reckon the number of people and services the measure would require the city to cover. For example, based on Census data about population and income distribution in Seattle, the Budget Office estimates that ensuring “No family pays more than 10 percent [of their income] for child care” would cost the city between $30—$49 million annually in the form of subsidies to parents. Ditto for the $16—$24 million the Budget Office estimates the city would need to pay in small business subsidies to “Increase child care pay to $15 per hour” within three years. Other costs—Required Certification, Enhanced Training, Mentoring/Apprenticeship, and Other requirements (administrative overhead, basically)—are similarly based on Census numbers and the costs of analogous, existing programs. (By the way: the lower numbers in the Budget Office’s analysis are based on existing levels of early child education and care, while the higher numbers are based on the expectation that more Seattleites will use these services as they become more affordable.) But remember: all of this assumes a strong interpretation of Prop 1A’s goals—that everything which might cost the city money will cost the city money.

(The Budget Office analysis also assumes that Prop 1A’s implementation would be immediate and total, which isn't consistent with its language about “setting milestones” and “consult[ing] with stakeholders.” The Budget Office frankly acknowledged this when I talked to them; it’s the sort of necessary simplification that’s standard in economic modeling.)

The bottom line is that if implemented, Prop 1A would cost Seattle taxpayers a couple million dollars per year. Or a hundred million. Or some amount in between. It all depends on whether Prop. 1 A's goals turn out to be aspirational vs. mandatory.

I’m going to take off my ‘objective’ reporter’s hat for a second and just make judgment call: I don’t think anyone knows. Not Pacifica Law Group (whose memo arguing that Prop 1A does create a mandate was leaked to the Seattle Times’ editorial page, though the city has refused to let anyone else see it on the grounds of attorney/client privilege); not Smith and Lowney; and neither opponents nor proponents of the measure. And until we do know, claims about how much the measure will cost are at best conditional speculation and at worst calculated obfuscation.

So good luck in November, Seattle voters. You're being asked to consider a measure with a variable price tag and uncertain implications. What's more, you must decide whether instituting Prop 1A is worth rejecting Prop 1B (and vice versa), thanks to the city council's decision to raise the stakes by running the measures in competition with each other. The deciding factor for this November's early education measures might well turn out to be the electorate's willingness to flirt with bold risks.