"Transit Communities" Amendment Could Allow More Density Near Frequent Transit Service

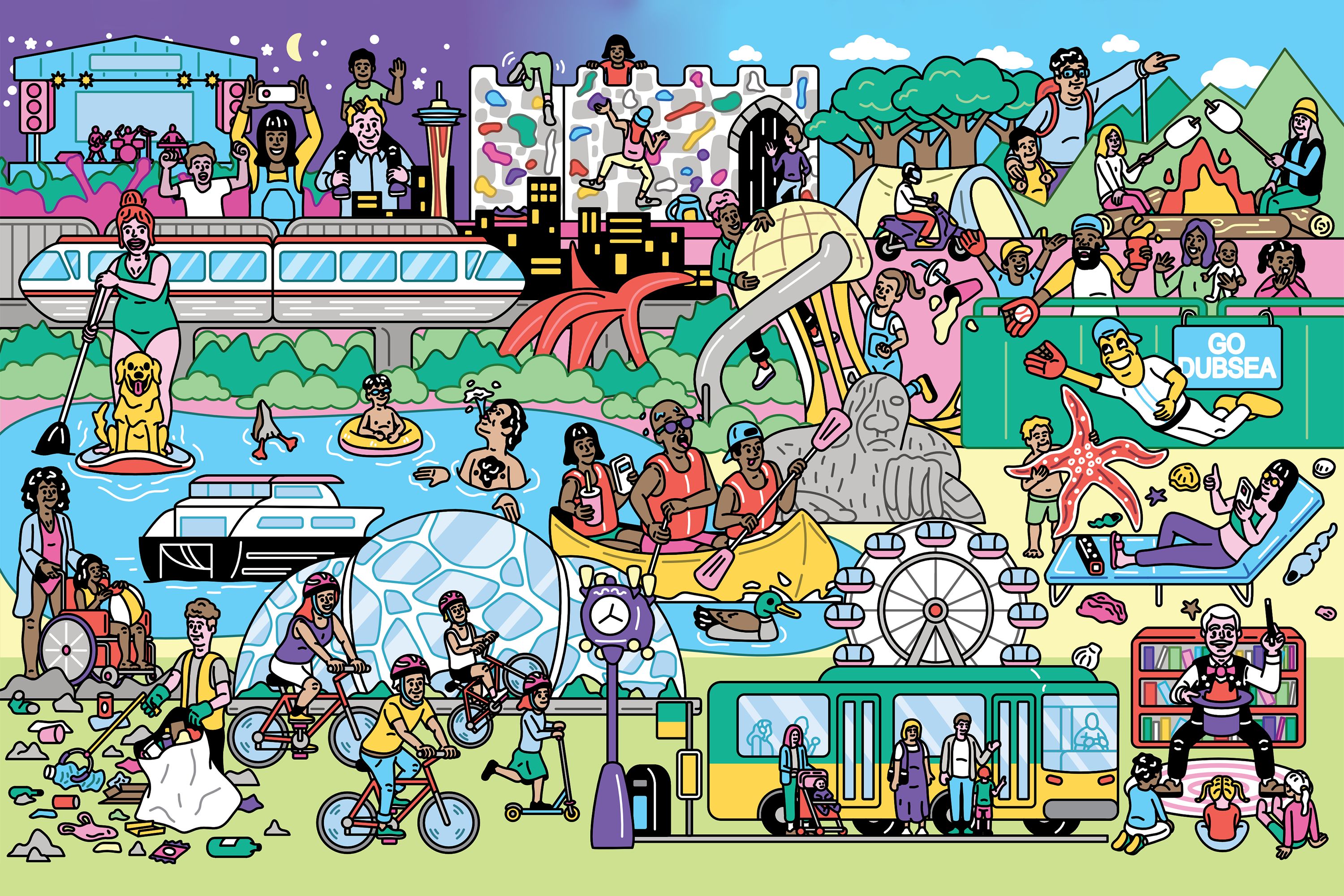

Image via city of Seattle. Circles represent "potential transit nodes."

The city council's annual ritual of updating the city's comprehensive plan—the master document that guides development in Seattle—has been relatively calm this year, save for one amendment that has raised eyebrows among some single-family neighborhood activists: A new land-use designation known as "transit communities," defined in the legislation as "complete, compact, connected places that offer a sustainable lifestyle, generally within a ten-minute walk of reliable, frequent transit."

"Through a planning process for establishing transit communities, the City would involve neighborhood stakeholders and seek their recommendations for refinements of transit community boundaries, designation of the transit community category, potential zoning and design guidelines changes, and investment needs and priorities," the amendment says.

Innocuous as that sounds, neighborhood activists worry that the amendment, which will add a new category to the existing urban village and urban center designations (areas where growth is expected and encouraged through zoning changes and targeted investments) will lead to upzones in single-family neighborhoods.

And they aren't exactly delusional. A handful (I count four) of the designated "transit nodes" that would be at the center of the still-theoretical "transit communities" are, indeed, in areas that are either zoned single-family or directly abut single-family neighborhoods—in Northeast Seattle, North Seattle, Ballard/Crown Hill, and the Central District.

And, as council central staffer Rebecca Herzfeld confirmed yesterday, transit communities oustide urban villages and urbance cneters "would be considered in similar way as an urban village or center: The city would go through the planning process to look at them as potential urban villages and do a neighborhood plan and set up potential growth targets … to take advantage of the frequent transit service in that area."

"These are areas that are not quite urban villages but have some capacity to absorb additional growth," council member Richard Conlin said.

That's exactly what single-family neighborhood activists are afraid of. Two neighborhood activists from two of those neighborhoods—Central District resident Bill Bradburd and Ballard resident Kirk Robbins—spoke against the amendment yesterday.

Robbins, who spoke first, lectured council members about "the real world," where Metro is contemplating a 17-percent service cut if state legislators fail to provide it with new funding options. "This is not the right time to go forward with this," Robbins said. "It's based on projections of service that seem wholly unrealistic at this time."

"We’re still remarkably unclear about how these transit communities are really supposed to work and how they fit in with the urban village construct," Bradburd told the committee.

(Contacted later, Bradburd said the transit communities policies "are pretty ill-defined and really are muddying up the Comp Plan." Bradburd, a member of the Seattle Neighborhood Coalition, also pointed me to a blog post about why the group opposes the transit communities strategy.)

Of the council members at yesterday's meeting, Tim Burgess—running for mayor against ardently pro-density incumbent Mike McGinn—seemed the most sympathetic to the single-family activists' concerns. "Many in the community are reacting to [the fact that] we’re stepping outside of our urban villages and urban centers" in identifying areas that might be ripe for more density, Burgess said. And, echoing Robbins, he added, "If we lose 17 percent of our transit service or worse in the coming years, a lot of this framework and strategy starts to fall apart."

To that, Conlin responded that the council should take a longer view than the immediate future in adopting land-use policy for the city. "We can’t do our planning on the assumption that everything’s going to fall apart." The original comprehensive plan, he noted, was passed in the same year that Sound Transit lost its first vote.

In the end, despite Burgess' hemming and hawing, the committee passed the amendment unanimously.