City

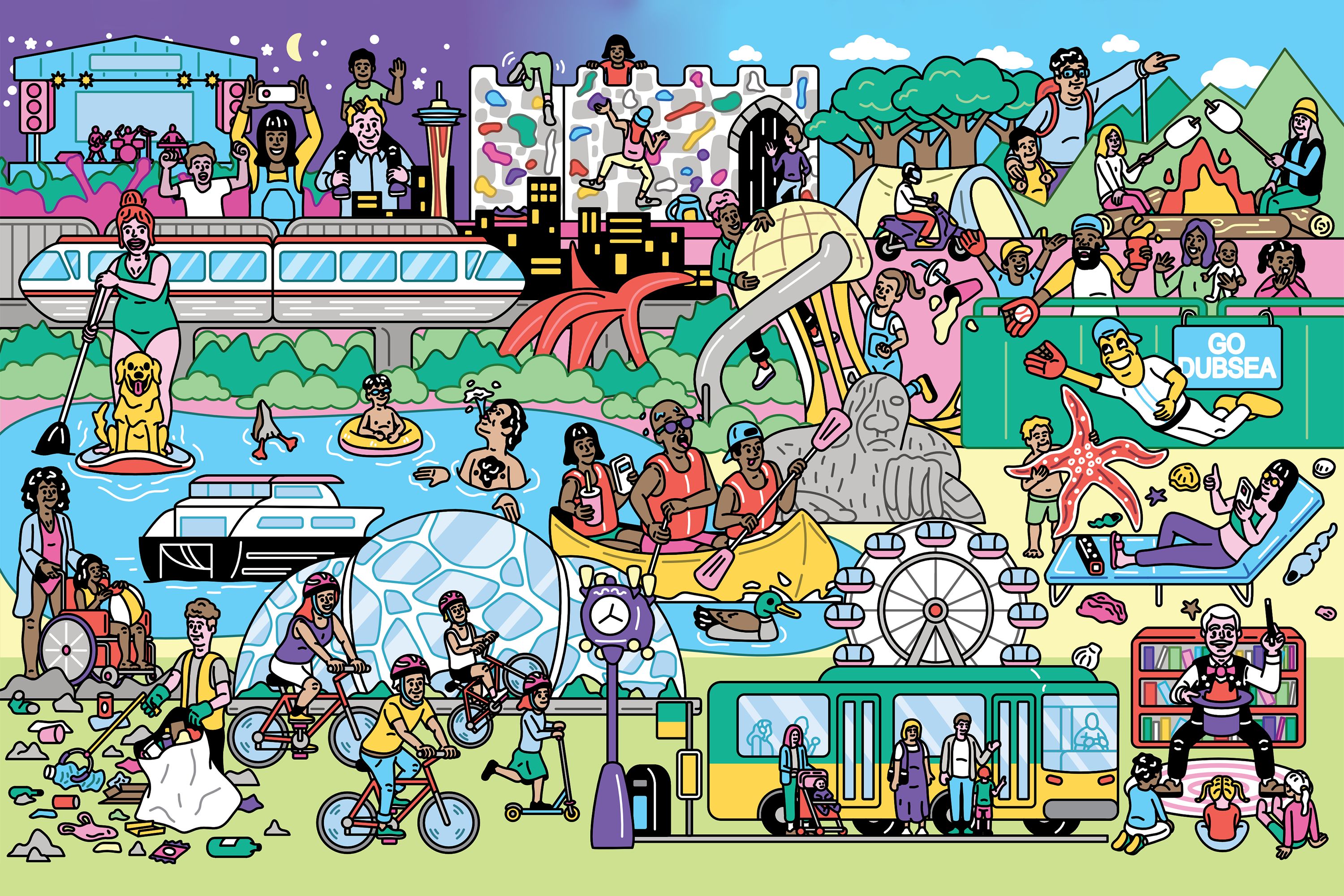

Should Transit Be Practical or "Fun"?

Jarrett Walker and Darrin Nordahl---authors, respectively, of Human Transit and My Kind of Transit---

discussed a central question in public transit planning this afternoon: Utilitarianism (the premise that transit should serve the most possible people, as frequently as possible, as reliably as possible, in the largest possible area, for the least amount of money) and "fun" (the contention that if transit agencies want drivers to put down their keys, they need to make transit enjoyable.)

Taking up the latter position: Walker, who argued that transit can be simple if planners simply take a hard look at the underlying "geometry." Although an "ideal" transit system, he said, would involve routes laid out in "very straight lines, operating in a grid pattern, about 800 to 2,000 feet apart," transit in the real world inevitably involves not just more complicated geography (if Seattle could run everything on a grid system, our transit problems would be largely over) but tradeoffs.

For example: Do you want higher ridership, or a larger (and thus more equitable) service area? Do you want to primarily serve peak-hour commuters, or to spread service out so that people can access it easily throughout the day? Should security funds be spent primarily on technology like closed-circuit cameras (which help catch criminals after the fact) or on-duty officers (whose presence makes women, in particular, feel safer and more likely to ride)? Do you want to minimize transfers, or have a less complicated network?

Rather than focusing fetishitically on technology, Walker said---an argument that harks back to the monorail days, when monorail proponents argued that only their specific technology could possibly serve West Seattle and Ballard---Walker argued that we should focus on what mode works best for what route, in terms of serving the most people, and the largest geographical area, for the least amount of money. "The assumption that people bring to this field is that the most important decision is the choice of product," Walker said. "I understand that you like this vehicle, but do you like this vehicle even more than you like getting where you're going?"

As an example of a system that segregates transit users---you're a tram person, but I'm a bus person---Walker pointed to a map of the Melbourne tram system, which showed only tram connections, not bus connections---the result being that, if you followed the map, a short east-west trip would turn into a circuitous ride to a tram stop far to the south and back again. In contrast, if the map included bus routes, a rider would be far more likely to just transfer from the first stop to a bus heading west. "I like to say that instead of 'requiring transfers,' we offer connections," Walker said. "Word choices, and mapping choices, are very important."

Taking up the latter position: Nordahl, who argued that transit agencies will never get people to switch from their cars to transit if they don't make riding transit enjoyable.

"I have a guilty admission: I love cars. I really, really love automobiles. I love the thrill that I feel when I drive in my automobile. I love the freedom that I feel when I drive in my automobile," Nordahl said. The job of transit agencies, he suggested, should be to recognize riders' desire for that hedonic experience---that is, transit should be fun---and do their best to provide it.

"What car makers do is, they prey on our emotions. They know what excites us and they know how to get someone to choose one product over another product," Nordahl said. "What I think is missing [in transit planning] is the emotional side---how can we design public transit systems" in a way that appeal to people's emotions? Nordahl noted---fairly, as his slides of identical bus after identical bus in cities around North America made clear---that buses all tend to look the same. They're white, boxy vehicles with little character, and when they aren't white, they're wrapped in ugly ads that prevent riders from seeing out and prevent potential riders from seeing in.

But, Nordahl said, there's another way. Davenport, Iowa, where he's from, has recently bought a fleet of cool-looking, gaudily-colored buses, which feature sky lights, big, clear windows, entertainment screens, and lots of room to stand, move around, and interact with other passengers. Whatever you may think of TVs on buses (I'm a firm thumbs-down), Nordahl said, "As long as we're spending money, and as long as we're spending design energy, to make the best and most vital streets and parks and public spaces, why shouldn't we do that for public transit as well?"

When I asked Nordahl, during the Q&A, how his plan could possibly be affordable---how, in a transit system built on economies of scale, where buses are all manufactured on a few basic designs, transit systems could pay for his quirky skylighted, TV-broadcasting buses---he said it was simple: Entrepreneurs would figure out ways to make buses cheaper (clear windows, for example, are cheaper than the far more common tinted windows), and transit agencies would figure out ways to build buses more cheaply in the United States. Currently, transit agencies are constrained by federal requirements that a certain percentage of their buses consist of materials made in the US; however, some transit systems---the Seattle Streetcar, for example---buy European designs and build the actual systems in the United States.

Ultimately, although I'm sympathetic to the idea that transit shouldn't be unpleasant, I fall down firmly in Walker's camp---frequency, reliability, and availability is more important than how pleasant the service is. Like Nordahl, I love cars, but ultimately, what's more important for me, in any transit mode, is how well it functions for me, and a '91 Honda does just as well (or, to be honest, better) than the '76 MG I'd love to own. If a regular, old, white-painted bus gets me there as quickly as the fancy new skylighted, bright-red circulator, and at lower cost, I'll take the regular old bus any day.

Taking up the latter position: Walker, who argued that transit can be simple if planners simply take a hard look at the underlying "geometry." Although an "ideal" transit system, he said, would involve routes laid out in "very straight lines, operating in a grid pattern, about 800 to 2,000 feet apart," transit in the real world inevitably involves not just more complicated geography (if Seattle could run everything on a grid system, our transit problems would be largely over) but tradeoffs.

For example: Do you want higher ridership, or a larger (and thus more equitable) service area? Do you want to primarily serve peak-hour commuters, or to spread service out so that people can access it easily throughout the day? Should security funds be spent primarily on technology like closed-circuit cameras (which help catch criminals after the fact) or on-duty officers (whose presence makes women, in particular, feel safer and more likely to ride)? Do you want to minimize transfers, or have a less complicated network?

Rather than focusing fetishitically on technology, Walker said---an argument that harks back to the monorail days, when monorail proponents argued that only their specific technology could possibly serve West Seattle and Ballard---Walker argued that we should focus on what mode works best for what route, in terms of serving the most people, and the largest geographical area, for the least amount of money. "The assumption that people bring to this field is that the most important decision is the choice of product," Walker said. "I understand that you like this vehicle, but do you like this vehicle even more than you like getting where you're going?"

As an example of a system that segregates transit users---you're a tram person, but I'm a bus person---Walker pointed to a map of the Melbourne tram system, which showed only tram connections, not bus connections---the result being that, if you followed the map, a short east-west trip would turn into a circuitous ride to a tram stop far to the south and back again. In contrast, if the map included bus routes, a rider would be far more likely to just transfer from the first stop to a bus heading west. "I like to say that instead of 'requiring transfers,' we offer connections," Walker said. "Word choices, and mapping choices, are very important."

Taking up the latter position: Nordahl, who argued that transit agencies will never get people to switch from their cars to transit if they don't make riding transit enjoyable.

"I have a guilty admission: I love cars. I really, really love automobiles. I love the thrill that I feel when I drive in my automobile. I love the freedom that I feel when I drive in my automobile," Nordahl said. The job of transit agencies, he suggested, should be to recognize riders' desire for that hedonic experience---that is, transit should be fun---and do their best to provide it.

"What car makers do is, they prey on our emotions. They know what excites us and they know how to get someone to choose one product over another product," Nordahl said. "What I think is missing [in transit planning] is the emotional side---how can we design public transit systems" in a way that appeal to people's emotions? Nordahl noted---fairly, as his slides of identical bus after identical bus in cities around North America made clear---that buses all tend to look the same. They're white, boxy vehicles with little character, and when they aren't white, they're wrapped in ugly ads that prevent riders from seeing out and prevent potential riders from seeing in.

But, Nordahl said, there's another way. Davenport, Iowa, where he's from, has recently bought a fleet of cool-looking, gaudily-colored buses, which feature sky lights, big, clear windows, entertainment screens, and lots of room to stand, move around, and interact with other passengers. Whatever you may think of TVs on buses (I'm a firm thumbs-down), Nordahl said, "As long as we're spending money, and as long as we're spending design energy, to make the best and most vital streets and parks and public spaces, why shouldn't we do that for public transit as well?"

When I asked Nordahl, during the Q&A, how his plan could possibly be affordable---how, in a transit system built on economies of scale, where buses are all manufactured on a few basic designs, transit systems could pay for his quirky skylighted, TV-broadcasting buses---he said it was simple: Entrepreneurs would figure out ways to make buses cheaper (clear windows, for example, are cheaper than the far more common tinted windows), and transit agencies would figure out ways to build buses more cheaply in the United States. Currently, transit agencies are constrained by federal requirements that a certain percentage of their buses consist of materials made in the US; however, some transit systems---the Seattle Streetcar, for example---buy European designs and build the actual systems in the United States.

Ultimately, although I'm sympathetic to the idea that transit shouldn't be unpleasant, I fall down firmly in Walker's camp---frequency, reliability, and availability is more important than how pleasant the service is. Like Nordahl, I love cars, but ultimately, what's more important for me, in any transit mode, is how well it functions for me, and a '91 Honda does just as well (or, to be honest, better) than the '76 MG I'd love to own. If a regular, old, white-painted bus gets me there as quickly as the fancy new skylighted, bright-red circulator, and at lower cost, I'll take the regular old bus any day.