Dinner Plans

Imagine that Tom Kundig (left) and William Belickis cooked up an easy collaboration: The chef knew what he wanted; the architect made it happen.

Image: John Keatley

BY THE TIME you read this, MistralKitchen will look like a restaurant. Light-catching liquor bottles will line shelves along a perforated stainless-steel wall behind the bar; a glow from a wood-burning Italian oven will double as the cool modern restaurant’s warm hearth. There will be tables and chairs. But on a windy day in October, the 5,000-square-foot South Lake Union space was a construction site. Slabs of plywood leaned against the walls, workmen snapped tape measures open and closed and made marks on the concrete floor. Everywhere, groups of shiny metal tubes stood upright, like cliques at a cocktail party. “They’ve already booked holiday events,” said the restaurant’s PR flack.

No one seemed worried. Though there remained just six weeks to turn this sawdust-sprinkled mess into a place where you’d want to eat, MistralKitchen was, for chef William Belickis and architect Tom Kundig, inevitable—a fait accompli so firmly rooted in their imaginations it simply had to be.

A year and a half ago, Kundig, a principal at Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen, had just won a national award from the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum—a big deal. Belickis, meanwhile, had a devoted flock of foodie followers who worshiped at the altar of Mistral, his tiny culinary temple in Belltown. He was on the verge of something big, too, and both men knew it. One night, they met at the Fairmont Hotel. They had drinks. They trekked up to Capitol Hill, had pizza. Then they had more drinks. When the evening was over, they had a plan. “William was so clear on what he wanted,” said Kundig, a jeans-wearing boomer with a mellow, ’60s-rocker vibe. “What we were doing was fitting and finishing his idea.” Anyway, at a great restaurant, Kundig continued, “you don’t remember the architecture. The food, the ambience, everything sort of fits together and a magic happens. You never forget it for the rest of your life.”

That’s the kind of restaurant William Belickis dreamed of. In 2008, buoyed by the promise of financial backing, he sold his 10-table Mistral restaurant in Belltown, envisioning a dining destination on the scale of Vegas’s most elaborate eateries, where he could satisfy each guest’s personal desire—whether that be a casual cocktail or the most formal of multicourse meals.

{page break}

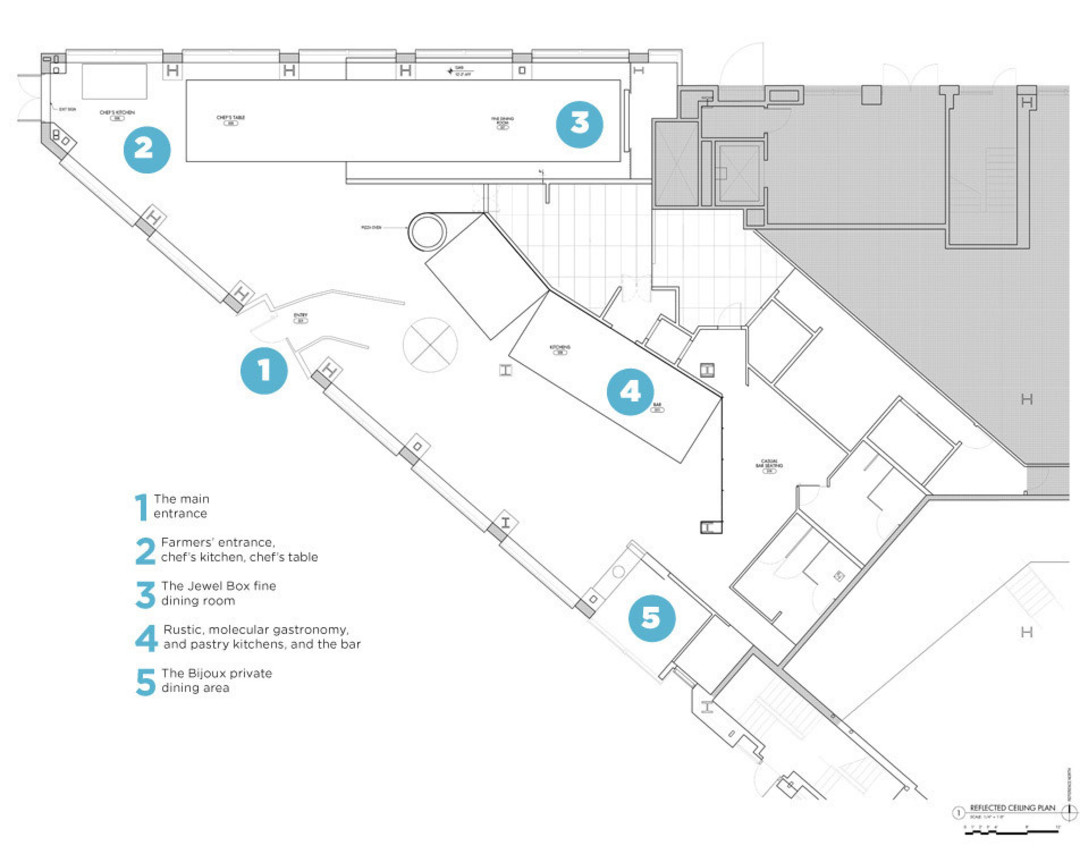

A moveable feast: Design plans fell largely into place on the night Belickis and Kundig met, before they’d chosen a space.

The tunnel-like entrance will be lined with seasonal produce, enticing guests as they arrive.

Here’s how he explained it to Kundig: Imagine a main dining room where guests ogle the goings-on in four open kitchens. The first three, presided over by a clan of cooks plucked from some of Belickis’s favorite restaurants, form a line in the center of the space. The rustic one (Belickis and project architect Les Eerkes came to nickname it the “Caveman” kitchen) is equipped with the wood-burning forno and a tandoor oven, where staff churn out “pizza, bread…pieces of meat with a big skewer. The whole idea is char, the primal sensation you have when you eat it.” Next to the Caveman kitchen, Belickis asked Kundig to picture a Spaceman kitchen where feats of molecular gastronomy are pulled off via induction burners and vats of liquid nitrogen. On the other side of the high-tech hub is the pastry station, where mad sugar scientist Neil Robertson (formerly of Canlis) shares tools and tricks of the trade with the spacemen. Cooks at each station chat directly with the diners seated nearby, answering questions and showing off their skills. Customers seeking less face time can choose tables further off in the dining room, where they eat a full meal or just pop in for a snack.

At a great restaurant, said Kundig, “you don’t remember the architecture.”

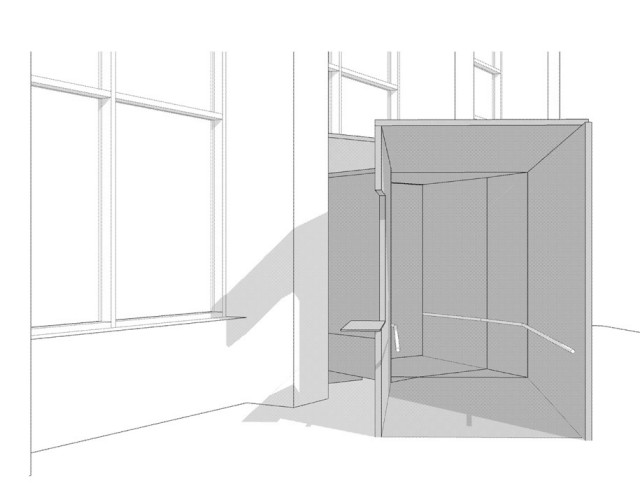

Belickis then talked about a fourth kitchen, set apart from the others, a command center from which he saw himself turning out fastidiously wrought consommes and seared scallops for a nearby chef’s table and a separate dining room—the Jewel Box—a reincarnation of the nary-a-menu-in-sight food church he’d built at Mistral.

Listening to Belickis’s vision, Kundig began to consider the practicalities. To his mind, the design of a restaurant must never dominate or distract from the food and the dining experience, but rather show them off in subtle yet crucial ways. Once Belickis settled upon the space in the 28-story West 8th Building—Kundig describes it as “Flatiron-shaped,” like the famous building in New York—the architect set about coaxing natural light into the right places, tweaking acoustics in the Jewel Box to create a hushed atmosphere of food worship, orienting vistas toward the South Lake Union street car route and the lake beyond so that the restaurant would feel connected to the neighborhood.

{page break}

Caveman cuisine: (Above) Guests at MistralKitchen might opt for clams roasted in the wood-burning oven and bathed in a white-wine, preserved-lemon, and garlic sauce, or tandoori leg of lamb with white beans, yogurt, and pomegranate. Or maybe both.

Image: Lindsay Borden

The oblong shape presented opportunities—and challenges. The original entrance was at the skinny tip of the iron where Eighth Avenue meets Westlake. When you walked through it, Kundig realized, you confronted the restaurant from a disorienting side view. So he moved the main entrance further down the wall along Westlake and opposite the row of open kitchens, adding a long corridor that leads guests out into the main dining room, where they can take in the charms—both primitive and pyrotechnic—at the restaurant’s inner core. They repurposed the original entrance to serve farmers and purveyors. “It’s that whole ‘Where does my food come from?’ thing.” said Belickis. “It comes in the door in full view of all the guests, and within minutes it can be on someone’s plate.”

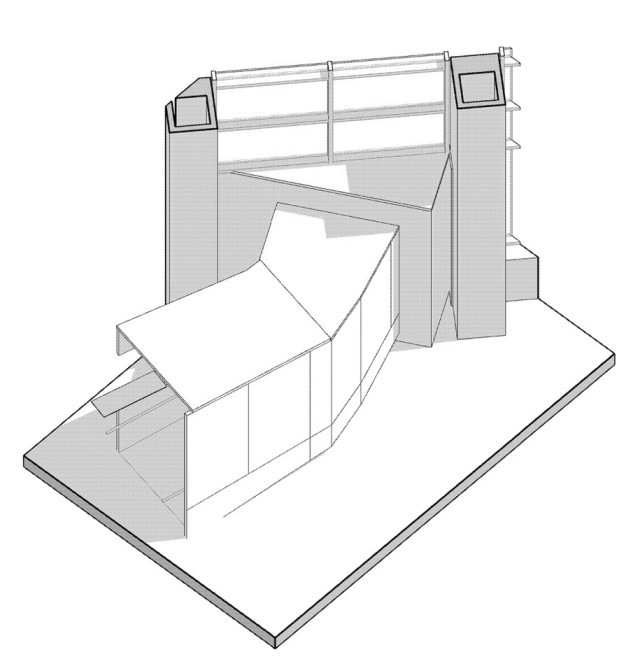

Walking through the construction site, Belickis paused in front of “the Bijoux,” a yet-to-be-enclosed rectangle facing the bar. With no permanent furniture, he said, the Bijoux could be a late-night lounge or a private dining room decorated to match any party a customer might dream up—a Moroccan theme maybe, with silky pillows lining the walls.

Looking at the bald steel cage, you could almost see it: handsome people lounging on low-slung sofas, sipping cocktails from gold-etched goblets. Maybe a belly dancer or two. You could almost see the revelers’ faces, lit up in that peculiar way that faces light up at certain restaurants—the rare places that manage to truly transport and enchant you, though you can never quite pinpoint how.

Tom Kundig (Principal) and Les Eerkes (Associate), Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects, 159 S Jackson St Ste 600, Pioneer Square, 206-624-5670; oskaarchitects.com

William Belickis (Chef and Owner), MistralKitchen, 2020 Westlake Ave, South Lake Union, 206-623-1922; mistral-kitchen.com