High Hopes

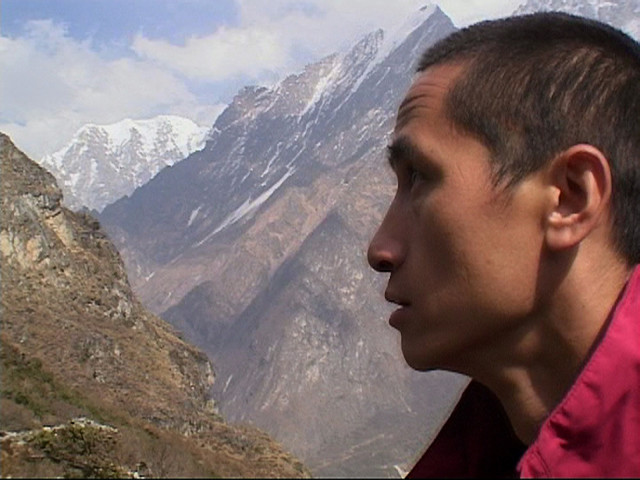

Go East, young man: Tenzin Zopa searches for his master. (photo courtesy Oscilloscope Pictures)

If we’re going to question organized religion—and we should, given the frequently unyielding power of its grip on the mass populace—could we please remember to interrogate the methods of all faiths?

The thought crossed my mind with increasing urgency during Unmistaken Child, Nati Baratz’s carefully constructed, beautifully shot but ultimately unsettling record of the search for the reincarnation of a Tibetan master that left me dumbstruck in ways I’m sure Baratz did not intend.

The documentary begins in 2001 after the passing of Lama Konchong, which leaves Tenzin Zopa, his 28-year-old disciple, visibly wounded and achingly alone. Defying his family, Tenzin was just 7 when he went to study with his teacher and tearfully held his hand at the moment of his death. “I got this very, very lost feeling—almost like I want to give up many things,” Tenzin recalls in his imperfect English. “Because I never planned for my life, you see. I always say ‘yes’…and I didn’t think at all about what is going to happen next.”

Tenzin’s an appealing innocent with an open heart; no wonder Baratz saw him as the perfect guide through the Buddhist faith. But the filmmaker never seems to question whether feeling lost, always saying yes, and not thinking at all about what is going to happen next are healthy reasons for what happens next in his documentary. Lost people long for salvation even when, as in this particular case, salvation means roaming the countryside asking random villagers if they’ve seen a toddler who might be the spiritual return of an 84-year-old.

Some astrology as well as the sand pattern beneath Lama Konchong’s funeral pyre point Tenzin to the east and through startling rays of sunlight shining down upon lush hillsides blanketed in mist (cinematographer Yaron Orbach should be credited, too, for capturing the more humble beauty of the average human face and the shadows of anguish or showers of joy that cross that plain). Our intimate access to Tenzin, whom Baratz and wife met during a month-long course in Tibetan Buddhism at a monastery in Nepal, allows for an astoundingly methodical rendering of the means through which a child can be proclaimed the “unmistaken” reincarnation of an enlightened being (a years-long process that includes various tests—does the child grab for Lama Konchong’s rosary or the correct bell?—and certification from the Dalai Lama).

Baratz makes no attempt to hide the cringing dubiousness of the quest. Not everyone encountered seems sold on giving kids up to strangers; one villager flatly answers Tenzin’s inquiry with “I haven’t met any child with interest in the teachings.” And when Tenzin does happen upon the “fatty-fatty” one-year-old he’d described from a dream, we are privvy to, among many other distressing moments, scenes of the same child a few years later watching his parents abandon him while he touches Tenzin’s face and cries out, “Now I have no friends! Don’t let them go!”. This is especially painful because we earlier witness the boy’s father haltingly agree to the arrangement with the crushed sentiment, “If he works for the benefit of sentient beings then I can give my child up. Otherwise, who could give up his child for nothing?”

That’s what I’d like to know. (It also made me more than a little nervous that the camera’s presence may have helped to sway the father’s decision).

And here’s another question: Wouldn’t reincarnation be more useful if a wise soul returned to earth and affected its given community in new ways through its new body? I don’t think wrapping a kid in elaborate robes, propping him up on comfy pillows, and hailing him with pomp and circumstance best serves the spiritual needs of people just trying to survive the trials of everyday life.

Audience of One, at the other end of the religious spectrum, has easy fun at the expense of some crackpot Christians in San Francisco. Pastor Richard Gazowsky claims he got a message from You-Know-Who telling him to be “the Rolls Royce of filmmaking.” Very quickly he leads his church into debt trying to produce Gravity: The Shadow of Joseph, a sci-fi chronicle of Joseph’s rise in Egypt that includes, for instance, a scene set in what novice director/screenwriter Gazowsky describes as “a Paris café in ancient times—a futuristic, ancient Starbucks deal.”

The bills mount after Gazowsky, through the initial help of German financing, heads to shoot some feeble footage in Italy with his WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) film company. Some of the barely paid, non-Christian crew begins to grumble (“He doesn’t do physical labor so he has no idea.”). One of the non-paid, amateur actors has a meltdown; when Gazowsky tells him not to “trip” the guy guffaws, “You’re telling me not to trip when I’ve seen your church services?!”

It’s all good for a laugh at mass delusion until you realize that mass delusion is more creepy than funny; Gazowsky actually tells his congregation they’ll be pioneers of the first colony on another planet. Director Michael Jacobs hasn’t found what drives his unstable anti-hero. We’re told in a title at the film’s opening that Gazowsky saw his first movie at age 40 but not why it took him so long. Who the hell is this nut? Tension between the man and his aged mother, who founded the church and confesses she wishes she hadn’t given her son the reins upon her retirement, goes unexplored. We’re left with a 90-minute look at inevitable, sometimes darkly amusing disaster but no understanding of the bigger tragedies beneath it.