The Boys in the Boat Reminds Us How Much Seattle Has Changed

George Clooney’s The Boys in the Boat transports viewers to a long-gone version of Seattle.

In a climactic scene from George Clooney’s new film adaptation The Boys in the Boat, famed Seattle Post-Intelligencer journalist Royal Brougham cries out over transatlantic airwaves, “An underdog team for an underdog nation!”

Brougham, speaking of the triumphant University of Washington crew at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, tailored that line for a national audience. But those eight Husky rowers represented a kind of twofold underdog. Because as far as Depression-era America went, Seattle was the dregs.

The Emerald City in the 1930s was a place of saw-chewed butt logs, tin-roof shacks, and mud-encrusted rail lines, all painted in wonderful detail by author Daniel James Brown in Clooney’s source material, a 2013 nonfiction best-seller. With The Boys in the Boat, Brown created a pitch-perfect time capsule of down-on-its-luck Seattle, a hardscrabble, lunchpail town epitomized by protagonist Joe Rantz. Brown describes “men in fraying suit coats, worn-out shoes, and battered felt fedoras,” who “stood in long lines, heads bent, regarding the wet sidewalks.”

These days, college crews don't compete as a unit in the Olympics. But in 1936, the University of Washington men's team was sent en masse to Berlin.

It’s astonishing that such destitute settings produced a gold medal rowing squad—and it’s equally astonishing how far the city has drifted from its blue-collar roots. Together, Brown’s book and Clooney’s film form an excellent lens with which to chart our 90-year civic transformation. SoDo’s infamous Hooverville might be gone—unless you count the eponymous dive bar—but there are other local features that link these two eras. If you get out on the lake early enough, you can still see those collegiate “eights” flying across the cool autumn water.

The first (and most critical) stop for Boys in the Boat sightseers is the ASUW Shell House, a WWI-era airplane hangar acquired by the university to house its rowing team in 1919. Designated as a historic landmark in 1975, the Shell House looms yet over Union Bay at the inlet of the Montlake Cut, a quarter mile east of the Montlake Bridge. It’s here where protagonist Rantz signed up for freshman tryouts, and in the film, it’s where he weathers many a workout montage. Even more impressive, it’s where British boatbuilder George Pocock—alone in his second-story workshop—constructed the world’s finest racing shells, used by “virtually every major rowing program in the country.”

The Conibear Shellhouse still stands on the UW campus. But it was recreated in a soundstage for the movie.

Both hangar and workshop remain intact, filled with Pocock’s cedar boats, spruce oars, and even a 1930s Philco transistor radio hooked up to Royal Brougham’s original Olympic broadcast. (The UW crew program moved its base of operations over to a new facility in 1949.) Nicole Klein, the UW Department of Recreation’s Capital Campaigns Manager, has led a six-year fundraising effort to refurbish the structure. “We’re finally at the tail end,” she says. “The money’s almost there. People kept telling me to wait for the movie. I said, If we wait for the movie to start fundraising, honestly, the building’s going to fall down.”

Renovations are set to begin over the next few years. In the meantime, public tours of the ASUW Shell House run 3–4 times a month and are scheduled through the University of Washington rowing website. Fans of the book and film will experience unmistakable flashbacks upon entering the space—it looks just the same in person.

Somehow, Hollywood being Hollywood, it’s not. Improbable as it seems, George Clooney’s The Boys in the Boat—as Northwest of a movie as you’ll find in theaters all year—was filmed almost entirely outside the Northwest. In the case of the Shell House, set designers took electronic scans of the historic building and recreated it in a sound studio. Lake Washington found its analog in Cotswold Country Park, a marshy set of irrigation ponds some 30 miles northeast of Bristol in the United Kingdom.

This will leave some Seattle viewers feeling vexed. The good (or possibly bad) news is that it worked. The Boys in The Boat is an aesthetically handsome film acted by tall, gorgeous people. It leaves out the Grand Coulee Dam and the Olympic time trials at Princeton, but it gets more right than it gets wrong. Just as important, it’s fun to watch and moves at a pace appropriate to its subject matter. There’s nowhere near enough rain, nor looming Cascade Mountains, but we locals will savor a recreated shot of industry-choked downtown, where the Smith Tower rises, per Brown, “like an upraised finger, toward somber skies.” And we can take further solace by visiting the real-world landmarks from Brown’s book, which, like the Shell House, will be around long after Clooney’s movie sets have been torn down.

Director George Clooney on set.

The heart of this story lies out on the water, and it’s Seattle’s lakes that provide the most direct window into the experience of a 1930s rower. When UW crew coaches Al Ulbrickson Sr. and Tom Bolles announced final lineups for the freshman boats on November 28, 1933, Joe Rantz and co. took their new shells on a celebratory lark.

“A light but cutting wind ruffled the water,” writes Brown of that influential outing. “The boat slipped onto the surface of Lake Union, the noise of city traffic fell away… To the south, the amber lights of downtown Seattle danced on the waves. Atop Queen Anne Hill, ruby-red lights on radio towers winked on and off.”

Those city lights have proliferated in ways that Joe Rantz couldn’t have imagined. But the radio towers stand in the same spot, still winking, and the “huge drafts of frigid air,” to our collective chagrin, remain.

The boys had their first transcendent rowing experience on Lake Union, but most of their training and racing happened on Lake Washington. The University of California, Olympic champs in ’28 and ’32, was UW’s chief Depression-era rival, and the schools’ biannual Seattle regatta ran from Matthews Beach up to Sheridan Beach. (The former is now a public park, the latter a private community club.) The race was an aquatic extravaganza that would put Seafair to shame. Fans mobbed every viewpoint on both water and shoreline. Press photographers circled in flimsy prop planes overhead. The UW student union rented an entire city ferry to hold spectators—also the marching band—and “A navy cruiser and nearly four hundred other vessels flying purple and gold pennants joined her.”

The Burke-Gilman trail was then a seldom-used track of Northern Pacific railroad. During the event, an open-sided spectator train, essentially a moving set of bleachers, departed Matthews with the starting pistol and chugged north at the same rate as the boats.

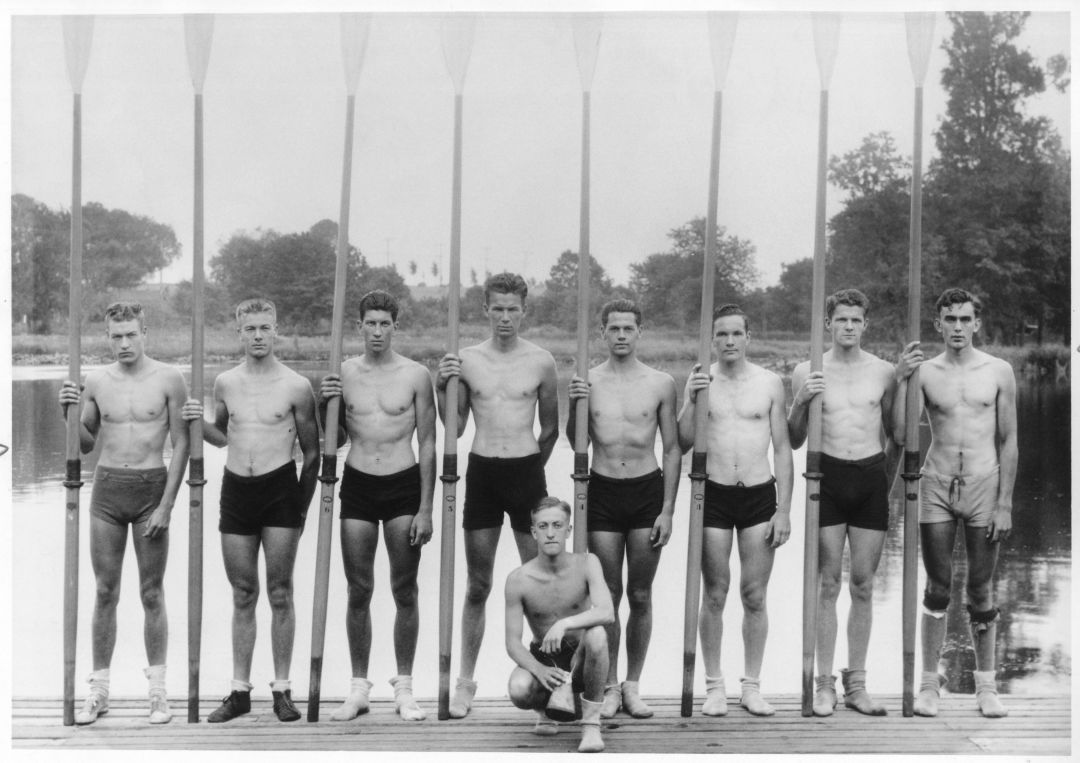

The famous Boys in the Boat.

If this sounds like a lot of buildup for a crew regatta, well, it is. Despite all the sawdust, bootlegging, and ragtime we encounter in The Boys in the Boat, the story’s most foreign aspect is the general public caring so darn much about rowing. The contemporary Windermere Cup can’t hold a candle to those 1930s races. “It’s hard to fully appreciate how important the rising prominence of the University of Washington crew was to the people of Seattle in 1935,” writes Brown. “Those boys in their boats were—length by length and victory by victory—suddenly beginning to put Seattle on the map.”

Today, 90 years after Joe Rantz and his boatmates first walked into the ASUW Shell House, Seattle is “on the map” for many reasons, rowing not chief among them. Those boys of ’36 were products of the farms, fisheries, and logging camps that formed the backbone of small-town Washington. They arrived at UW with chips on their shoulders and callouses on their hands. Today’s Emerald City, dominated by tech companies, lacks that spirit, but as we have our theatrical moment this Christmas, we can still get out on the lakeshore and celebrate the area’s maritime ethos—even if George Clooney would rather stay in Europe.