A Timeline of Mount St. Helens

May 17, 1980, one day before the eruption.

Image: Courtesy USGS

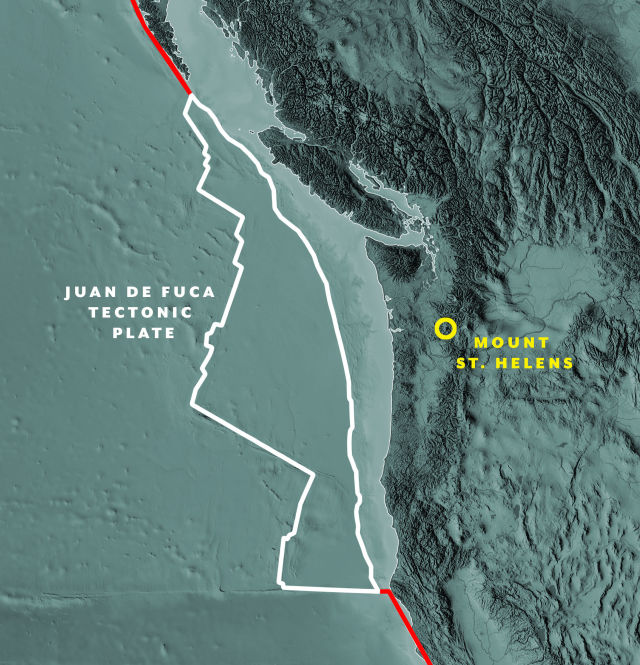

► ~300,000 years ago

The stratovolcano known as Mount St. Helens or Loowit formed when the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate subducted under the North American one.

Image: Shutterstock by Yarr65

~1850 BCE

The volcano experiences what scientists consider its biggest eruption ever, of 5–10 cubic kilometers of material, about five to ten times bigger than 1980.

~1000 BCE

A series of lava flows begins to form the edifice we now know as Mount St. Helens, making the peak younger than the Great Pyramids of Giza.

1792

Explorer George Vancouver names the peak after fellow Brit—Alleyne Fitzherbert, Baron St. Helens. The local Native American tribe had long called it Lawetlat'la, or “smoker.”

Spirit Lake circa summer 1968.

Image: Courtesy U.S. Forest Service

► 1950s–1970s

Spirit Lake, at the foot of the mountain, becomes a camping and fishing destination, lined with cabins, a YMCA camp, and the Mount St. Helens Lodge run by colorful WWI vet Harry Truman (nope, no relation).

March 27, 1980

Steam emerges from near the top of the mountain, marking the beginning of an eruption. It was preceded by several small earthquakes, a sign that magma was moving deep in the ground.

Spring 1980

Geologists converge on Vancouver, Washington, including 30-year-old U.S. Geological Survey volcanologist (and University of Washington PhD grad) David A. Johnston. No one’s ever been able to study an eruption like this up close before.

April 1980

Officials designate red (dangerous) and blue (permitted workers only) zones around the mountain; most residents are evacuated, though 83-year-old Truman refuses to leave, remaining in his cabin with 16 cats.

The last photo taken of David Johnston, on May 17, 1980. This site would eventually be re-named "Johnston Ridge" in his honor.

► May 18, 1980

A sunny Sunday begins with a 5.1-magnitude quake, leading to the largest landslide in recorded history and a lateral eruption of magma that flattens 600 square kilometers of forest. Johnston, perched on a ridge just to the north, radios to colleagues just before he’s instantly killed by the blast: “Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it!”

May 18, 1980

Fifty-seven people die—largely from asphyxiation—mostly in areas outside the red and blue zones, most fishing, camping, and hiking. A lahar, or mud flow, races down the Toutle River.

May 18, 1980, eruption column.

Image: Courtesy USGS

► May 18, 1980

The eruptive event ends about nine hours later, after a column of ash rises 18 miles in the air and some 1,300 feet of mountain blows off, reducing the height of Mount St. Helens to 8,366 feet.

May 1980

Ash coats the Pacific Northwest and drifts as far east as Wyoming; 540 million tons fall in total.

Summer 1980

Smaller eruptive activity continues through October, as geologists get the chance to study a major eruption firsthand. A few, visiting from volcano hotspot Hawaii, roast a pig on the pyroclastic flow, aka the scorching hot gas emissions. (The annual barbecue tradition still continues among USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory scientists, albeit in someone’s backyard.)

1982

Congress designates Mount St. Helens as America’s first National Volcanic Monument.

2004–8

A four-year eruption series looks markedly different from its famous 1980 predecessor. Though less instantly dramatic, these events include plumes of ash and lava extrusion that eventually build a dome 1,000 feet high.

2020

Mount St. Helens has rebuilt about 7 percent of the mass it lost in the explosive 1980 eruption.