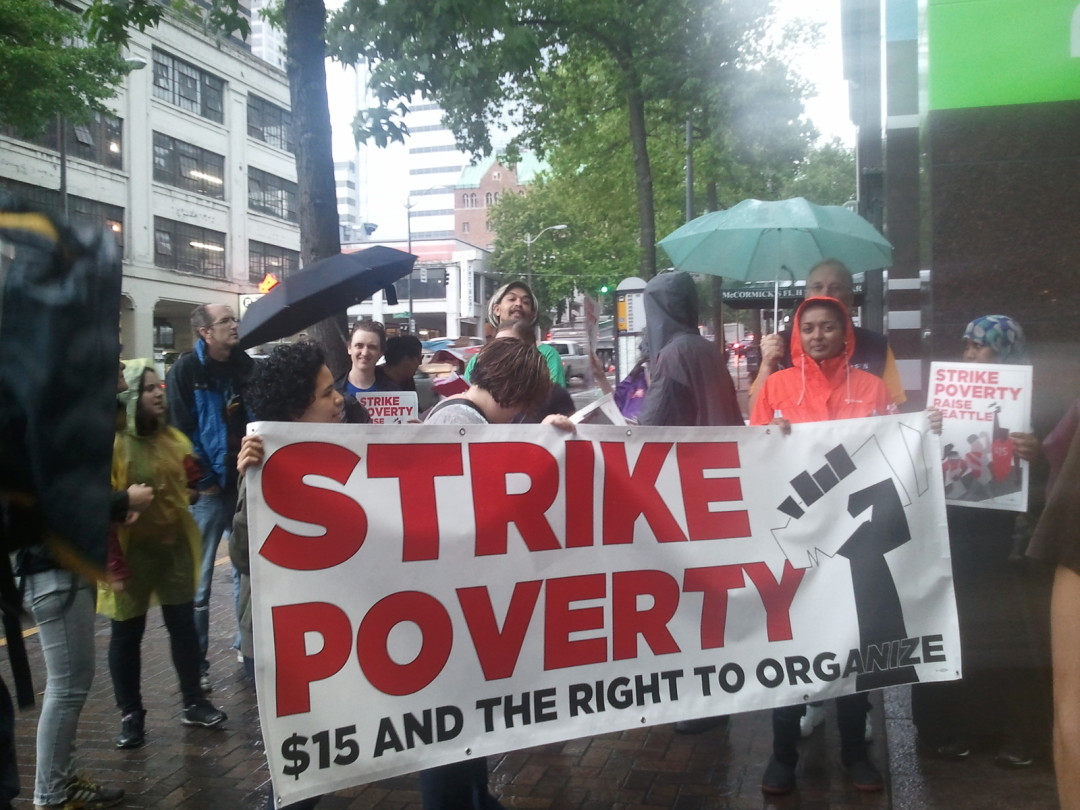

Workers Walk Out of Jobs Today to Join "Strike Poverty" Movement

Low wage workers hit the streets today as part of a "Strike Poverty" rally, the first ever coordinated nation-wide protest of low-wage workers, demanding a $15/hour pay and the right to organize without retaliation.

Washington state's minimum wage is currently $9.19/hour, the highest in the nation.

The protesters, many taking the day off, picked up a couple of on-the-clock workers along the way, who walked out when the protest showed up at the their door.

Two of these workers, Garrett McMahon and Nicholas Tyler, walked out in the middle of their shift at the Specialty's Cafe & Bakery in Columbia Tower in downtown Seattle. They were still sporting their brown Specialty's T-shirts and khaki pants when they joined the group of downtown strikers this morning to show their support.

The protests—think of it as Occupy meets organized labor—is part of a national movement that started in New York last November and has since found support in Seattle (last May) and over 50 other cities. Some of the other cities out striking today are New York, Detroit, St. Louis, and Los Angeles.

Today's action started when a crowd of about 20 workers gathered at Westlake Park at 7 am. By 7:30, the crowd had grown to around 100 people, chanting phrases like ""We're fired up!" "Can't take it no more!" and "You gotta beat back the boss attack!"

Kayla, a Top Pot employee, and Coulson, a former Starbucks employee who got fired for eating an unopened sandwich tossed in the trash, stepped up to the podium to speak out about their experiences working at low-wage jobs. Energy was high, especially when organizers streamed live video of sympatico protests in Tacoma and Missoula, Montana on a TV screen set up on stage.

Protestors watching a live feed of "Strike Poverty" in Missoula, MT during Seattle's protest, Aug. 29

Kayla told PubliCola that she has been living with her boyfriend because she can't support herself just on low-wage labor. "Most of us can't even afford to pay our rent...yes, we do make a higher wage than [all other] states, but that doesn't mean it's a livable wage," she said.

On stage, Coulson said, "It's not just us. When workers like us don't have enough money to afford the basics, it slows the entire economy."

In a sign that a raucous new ad-lib, spontaneous labor movement was leading established labor, David Rolf, president of the Service Employees International Union 775NW, came out to support the protesters today.

After some more rallying cries, the workers split up into groups and dispersed to neighborhoods around Seattle, such as Ballard, Capitol Hill, Rainier Valley, and Georgetown. The organizers coordinated via text messages and Twitter to figure out their protest routes for the morning.

The downtown contingent of about 20 members marched to Subway on Seneca St., in hopes of bringing out one of the employees working that day. None came out to join the effort, but the group stayed and chanted outside the Subway door as cars drove by with the occasional honk. One car's long, continuous honk could be heard in the background throughout the chants.

The next stop was Specialty's Cafe & Bakery in Columbia Tower. Along the way, two of the protestors sprayed "Strike Poverty" in red and white along a construction site wall on 5th Ave. A few of their comrades worried that the graffiti might get them in trouble wondering if it was legal. The pair assured their friends it was merely "chalk" and calmly continued to write out the words.

After arriving at Columbia Tower, the group chanted, "We're on strike, can't keep us down, Seattle is a worker's town!" and "Supersize my salary now!" as they waited for some protest recruits at Specialty's. A police car parked on the street stood by idly behind the group. The pair of workers—McMahon and Tyler—joined the group after a period of chanting under the Seattle rain.

McMahon, age 22, said he has worked in the food industry since he was 15. He got involved with the movement a couple weeks ago when he started talking to one of the recruiters.

"The stuff they were telling me was just a bunch of stuff I believed in, [having] worked in the food industry since I was 15," he said.

Tyler, 23, told a similar story. "I've pretty much bounced from retail job to retail job...and they're paying you at a rate that is pretty ridiculous," Nicholas said. "I have no college degree because I can't afford to pay for it, [so] I can't get the good jobs."

The two joined the group to head to the next destination: the Specialty's on 5th Ave and Union St., where McMahon's little sister was working.

While the protesters couldn't rally her or any of the other workers at this Specialty's to leave work, McMahon's sister brought out sandwiches for the group to snack on while they protested on the street corner.

In a sign that a raucous new ad-lib, spontaneous labor movement was leading established labor, David Rolf, president of the Service Employees International Union 775NW (a bonafide, and powerful local workers' union representing healthcare, property services, and public services) came out to support the protesters today. He believes that higher wages are necessary to maintain a healthy, sustainable economy:

"The reality is that all the middle class jobs that were lost in the recession have been replaced by low wage jobs...If our economy is going to work for everybody, people have gotta stand up and walk. We cannot be the only first world nation with these levels of poverty, of low inter-generational social mobility, and inequality. It's not good for the economy, it's not good for our civic life, and even the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are publishing reports that say that this is bad for long-term economic growth."

He cited that, during the recession in 2009, 24 percent of all work in this country was low-wage work. He said that if our economy continues at current growth rates, that percentage will jump to 48.2 percent by the year 2020.

He also provided some statistics on the current low-wage workforce in America, saying that the low-wage workforce in this country is on average 28 years old. He said 25 percent of that workforce is over the age of 40, and 23 percent are raising kids.

If wages were to go up, he said, it is not certain how much of the burden would fall on consumers—but regardless, he thinks it would be worth it. [Riffing off a recent NYT article low-income wage, my editor Josh evidently agrees.]

Rolph concluded: "If that's what we have to do to support an economy that grows from the middle out, and a new American middle class accessible to all hard workers for the 21st century, then fine, that's what we need to do."