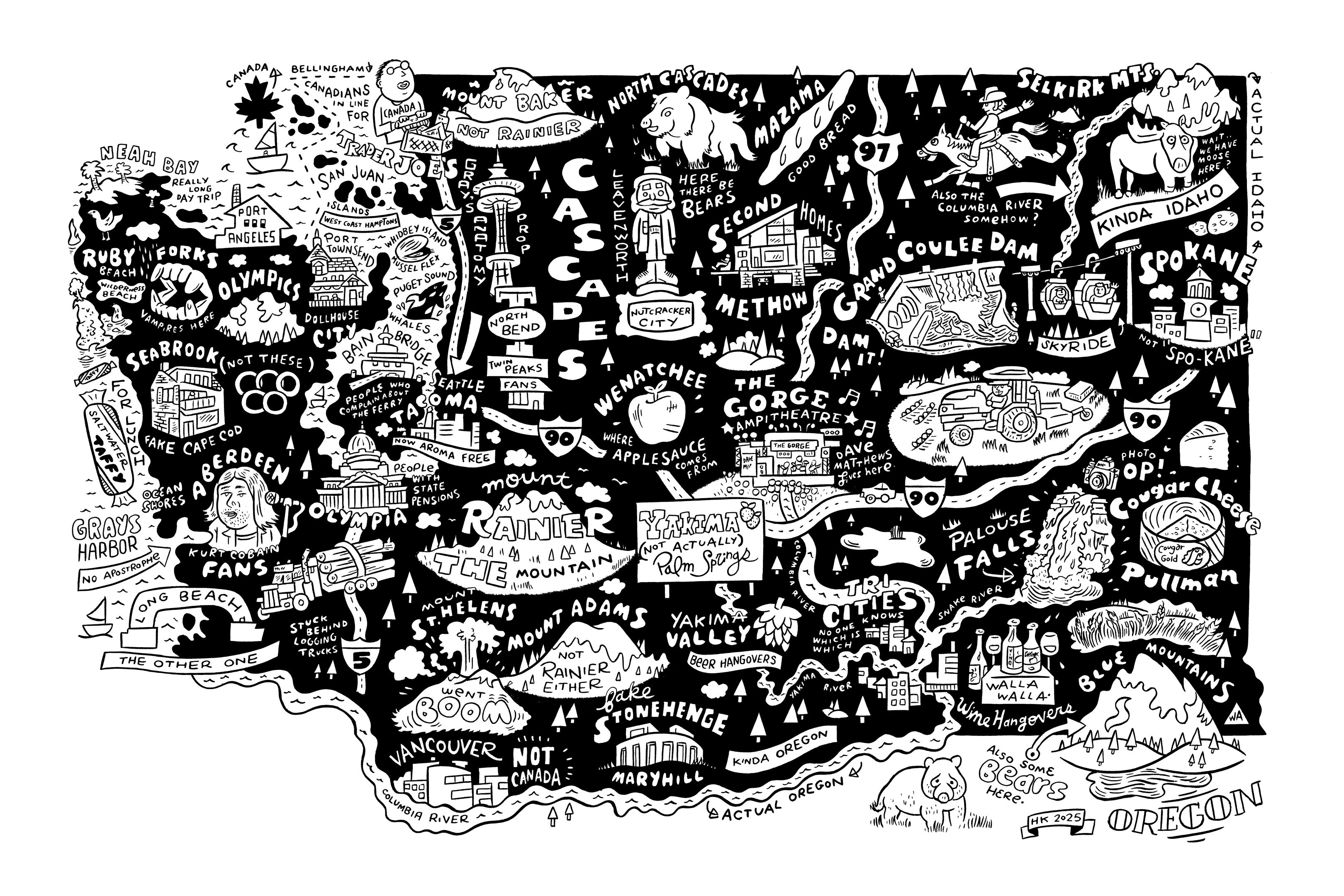

Seattle’s Historic Chinook Jargon Is Having a Moment

Image: Amiran White

If you traveled back in time and stepped onto the docks of Seattle around 1880, you might be surprised at one of the languages you’d hear. Rich in k sounds, with clicks and pops unheard in English, it might sound to your ears like a tongue from halfway around the world.

But Chinook jargon is as homegrown as it gets. Once widely spoken on the waterfront, in the courts, and in the stores of early Seattle—as well as in other parts of the Northwest, from Alaska down to California—it was a trade language, a lingua franca largely composed of words from Indigenous languages and a smattering of English and French. Although it faded from everyday usage around the Sound by the early twentieth century, traces of it remain in place names, local businesses, and more.

Image: Amiran White

In fact, the jargon never truly disappeared. Over the past few decades, its use has proliferated again in certain parts of the Northwest, treasured both for its links to the past and its adaptability to the modern world.

When the first European explorers arrived in the Pacific Northwest in the eighteenth century, about 20 distinct language families flourished from the Alaska Panhandle south to California’s Sacramento Valley, including the Wakashan family in British Columbia and Salishan around Puget Sound. Many Native nations, such as the Haida, Chinook, and Nuu-chah-nulth, were highly mobile, crossing the waters in canoes. Indigenous leaders argue that Chinook jargon thus predates contact with Europeans—Native people have long needed ways to communicate with each other amid complex, often mutually unintelligible tongues.

Image: Amiran White

The English and French fur traders who arrived in the late 1700s eventually peppered the jargon as well. David Robertson, a Spokane-based linguist who specializes in Chinook jargon, says the trading ships that arrived on the lower Columbia River around 1794 were the first to stay long enough for a stable jargon to develop. And while Chinook jargon originated in trade, Robertson says that from the start, “It’s [also] been a way to form and solidify personal relationships,” cementing friendships and intercultural marriages alike.

At the peak of the jargon’s usage around the 1890s, roughly 100,000 people spoke it from southeast Alaska to northern California, the Northwest coast to the Rockies. It was common in early Seattle, where it lent itself to place names including Alki (“in the future”), Tillicum (“people”), and Tukwila (“hazelnut”). While the language includes a large chunk of Chinookan—spoken by the Chinook Indian Nation—it also contains words from Coast Salish languages and Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootkan), as well as other Indigenous tongues. Different versions were spoken in different places, influenced by the Native nations of each area, among other factors. Of course, not everyone in early Seattle spoke it—one person who refused was Chief Seattle, who preferred his native Lushootseed.

Image: Amiran White

During the twentieth century, the number of people speaking Chinook jargon declined, in part because of racist policies that forbade speaking Native languages in schools. But in one area of Oregon, the language remained more important than ever. In the 1850s, the federal government forcibly moved members of more than 30 Native nations—who had called the Northwest home for millennia—to a reservation at Grand Ronde, Oregon. There, Chinook jargon became a tool for survival.

Justine Flynn currently runs Shawash-iliɁi Skul, the K–6 school operated by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. A Grand Ronde tribal member and Indigenous language advocate, she explains that when the various Native nations were forced onto a reservation together despite historical conflicts, “there was this need to settle in as a community and to create stronger ties, create unity…. What came out of that was Chinook jargon being the common language.”

That led to a tongue Native folks still use today, one that’s now often called Chinook Wawa. (Wawa means “talk.”)

Image: Amiran White

“It isn’t what we would call like a mother language that we have spoken since time immemorial,” says Flynn. “However, it is what we have at this moment, and the revitalization efforts pay homage to that—those elders, who prioritized that and kind of kept [it] safe for us.”

In the late 1990s, Chairman Tony Johnson of the Chinook Indian Nation came to Grand Ronde to kick off those revitalization efforts. Notably, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde have federal recognition—something the Chinook Nation still lacks—which means considerably more resources for education and cultural programming compared to unrecognized nations. (Although it remains to be seen exactly how much the current administration’s cuts will impact federal funding for Native programs.)

Johnson took on several language apprentices (including Flynn’s grandmother, Jackie Whisler Mercier), created a nearly 500-page dictionary (Chinuk Wawa: As Our Elders Teach Us to Speak It), and inaugurated an immersion program for kids. Today, the Shawash-iliɁi Skul offers immersion programs focused on Chinook Wawa as well as ancestral knowledge and practices.

Creating new generations of speakers feeds something profound in the kids that ripples throughout the community, Flynn explains. “If you don’t have language, you don’t have culture,” she says. “We can’t really truly understand how to do our lifeways if we’re not doing it in the language that [it] was taught in.”

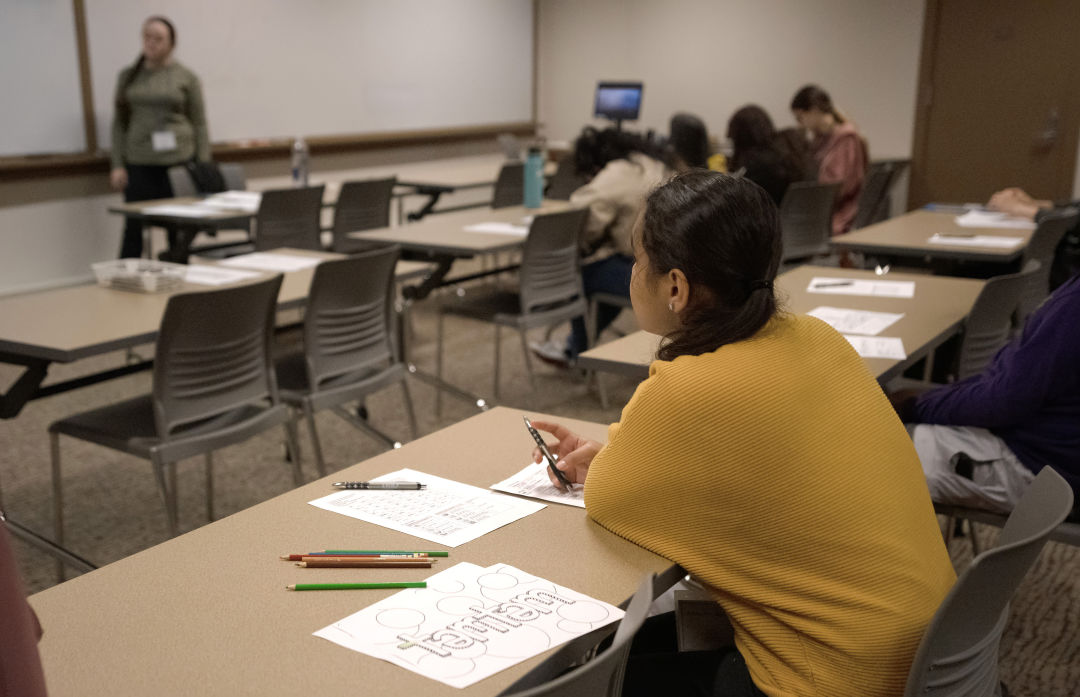

Image: Amiran White

There are opportunities for adults to learn the language, too. Around the early 2000s, Johnson helped teach the first courses of the Chinuk Wawa Language Program at Lane Community College in Eugene, Oregon. Today, the two-year program can be taken entirely online and is open to anyone.

While some Native languages are kept sacred and not taught to outsiders, this one has “always been about communicating with other people, and so we will always teach it to anyone who wants to learn,” says Carisa Chang, a Bremerton-based Chinook tribal member who teaches in the program.

For Chang, learning Chinook Wawa as an adult meant that she could understand tribal teachings in a way that hadn’t been possible in English. “You can’t really truly translate between languages.... There’s concepts you can’t express, right? And so for me it was like having a whole new worldview open up.”

Image: Amiran White

Chang created a keyboard for typing in the language and is at work on an app for learners; there is also an app created by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. And Chinook Wawa is still evolving: Chang notes that there’s even a word for cell phone now—lima-tintin, which means “hand ringing.”

Today, Robertson estimates there are about 500 people who can hold a conversation in Chinook Wawa. Chang says learning the language can be a window into understanding the place you live, including why many spots in the Northwest have the names they do.

There are other benefits, too. “This is a language of the first people that were here,” Flynn adds. “And so it is a language of this land, and the land needs to hear it too.”